Foreword

The last year has seen the People’s Republic of China (PRC) preoccupying the press, politicians and policymakers and not only because the Covid-19 pandemic spread out from the country. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the authoritarian regime in control of the PRC, is celebrating its centenary as a political party. Of all the major powers, the PRC has been a ‘winner’ over the past twenty years: Chinese power has grown substantially, to the extent that the PRC is now understood to be the world’s second most powerful country and a serious peer competitor to the United States (US).

In the United Kingdom (UK), the PRC is sometimes seen as overweeningly powerful. But is this necessarily true? Powerful though the PRC is, should Her Majesty’s (HM) Government be afraid of the CCP? How much should British policymakers take into account the CCP’s potential reactions?

In this Report, Charles Parton, a renowned expert on Chinese domestic politics and foreign policy and an Associate Fellow of the Council on Geostrategy, explains why HM Government will continue to have significant leverage. As he shows, foreign countries rarely suffer for long – or not as deeply as some suggest – when they anger the CCP, for the reason that the PRC is in need of foreign knowledge. Even when thrown into the diplomatic doghouse by the CCP, trade between a scolded country and the PRC often continues to grow or is replaced by trade with other countries, just as the benefits of Chinese investment are often exaggerated and often favour CCP aims.

While this Report focuses on the UK, much of its content is relevant to other free and open countries. It is vital reading for those who often underestimate the power of the UK and like-minded nations, as well as those who over-emphasise the reach and determination of the CCP.

– James Rogers

Co-founder and Director of Research

Council on Geostrategy

Executive summary

- At a time when the divergence of political, economic and values systems between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and free and open countries is growing, Her Majesty’s (HM) Government has a difficult balance to strike: how, in an increasingly globalised world, to maximise good relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), while prioritising the United Kingdom’s (UK) own security, values and prosperity. PRC foreign policy is increasingly built upon economic sticks and carrots. The implicit threat/inducement is that, unless the UK acquiesces to CCP aims, it will miss out in six areas: exports, investment in the UK, financial and associated services, Chinese students at British universities, tourism, and cooperation over climate change. The threat has been exaggerated. The contention of this Report is that the CCP’s sticks and carrots are neither as threatening nor as juicy, respectively, as generally portrayed.

- The PRC is different, and not just in size. In its foreign relations, the control of the CCP binds Chinese entities, whether business, cultural, academic, or political, to its aims or to ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy’, even if the CCP cannot in practice oversee all their activities and deal making. Outwardly it talks of ‘win-win’ and ‘a community of shared future for mankind’, but inwardly it sees mainly ‘struggle’ and ‘hostile foreign forces’. HM Government should pursue relations with the PRC, but with wide open eyes and with a clear recognition of the limits.

- Besides the use of economic sticks and carrots, two other elements are important to the CCP as it pursues its interests. The first is external propaganda work, to which the CCP devotes very considerable resources. The second is the united front strategy. This seeks to isolate the main enemy (the United States (US)), and to move other potentially hostile entities (such as the UK) to a neutral, or preferably a friendly, state. Propaganda seeks to influence from outside, while the United Front Work Department tries to mobilise resources from within its target through a series of actions on a spectrum ranging from acceptable influence (public diplomacy) to unacceptable interference and economic pressure.

- British policymakers should ‘seek truth from facts’, not from propaganda, nor from sources backed by the united front. A realistic view of the PRC is a first step. The PRC may well not become the superpower of the twenty-first century or even a superpower. Its rise may be unsustainable. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been hyped. Concrete projects and measures should be the focus, not mythmaking. It is refreshing to see that a UK minister has at last recognised openly that a free trade agreement is not on the cards.

- The list of countries which the CCP has put in the diplomatic doghouse is lengthening. It includes Australia, Canada, Japan, Mongolia, Norway, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, and the UK. The reasons are varied, but centre around two themes: either countries are perceived by the CCP as having gone against its ‘core interests’, or their policies are too proximate to those of the US. In particular, Australia appears to have been selected as a middle level power out of whom to make an example.

- CCP diplomacy has become ever more assertive, and at times overbearing. When another country transgresses its interests, there is an established CCP playbook on a sliding scale of aggression. Meetings of politicians and ministers are postponed or cancelled. Eventually political relations are put into the deep freeze. This political bark is often more successful than it should be. British ministers set great store by the importance of their visits and contacts, but they should realise that they are icing, not the cake.

- Five economic areas are often perceived as vulnerable to CCP pressure in the UK: exports, investment, financial services, students, and tourism. Consideration of the five areas suggests that while there is a price to be paid for upholding the country’s security, values and prosperity against CCP interference, concerns are overdone:

- Export trade for most goods will carry on regardless of the political storms so long as UK companies produce goods which the PRC wants, needs and cannot produce for itself, and as long as price and quality are right. Countries in the diplomatic doghouse with the PRC often see their exports rise during periods of bad relations.

- Chinese investment (comprising just 0.2% of the stock of the UK’s investment from abroad) benefits the PRC more than Britain: the PRC needs British technology, but its investments have not created significant employment.

- Potential for growth in financial services exports to the PRC exists (currently 0.4% of total of financial services exports; only two shares are listed on the Shanghai-London stock market connect programme), but to the extent that the Chinese economy requires services from abroad, London will remain the likely destination for considerable business, even if on occasions deals will be lost in order to make a propaganda point.

- As for students in UK universities, it is unlikely that the CCP will risk offending the Chinese middle classes, who in large numbers still want their children educated abroad, preferably in English-speaking countries.

- The same applies to turning off the tourist tap. That has happened with other countries in close proximity to the PRC, but by controlling package tours, not private tourists – the status of most Chinese tourists to the UK.

- Meanwhile, some worry that offending the CCP might lead to a lack of cooperation in combating climate change. But by numbers and size of effect no country risks suffering as much as the PRC. Millions are at risk on the eastern seaboard, while disturbed weather patterns pose a threat to precarious food security. Withholding cooperation on climate change is not an option for the PRC.

- HM Government needs to be clear eyed about the nature of the CCP and its aims, to see through its propaganda. Defying the CCP is not without pain, whose infliction is an integral part of its diplomacy. But that is no reason for exaggerating its potency. Making policy in line with British security, values and prosperity is essential if the UK aspires to be the global leader envisioned in the Integrated Review, rather than a global follower.

- The need for a strategy for dealing with the PRC, agreed and implemented across all government departments, remains pressing. Without one it will be difficult to counter unacceptable CCP influence on British policy. As part of drawing up such a strategy, HM Government would do well to:

- Carry out or commission research – before publishing it – on the six areas of threat/inducement (including both inward and outward investment);

- Increase the powers of the China National Strategy Implementation Group (NSIG) to coordinate and ensure the implementation of a consistent government-wide policy towards the PRC;

- Work out essential supply lines, resources, goods where the UK must be independent of the PRC;

- Be ready to provide temporary financial support to help diversification of exports where the CCP decides to inflict temporary economic losses; to explain the need for diversification to both business and academia; and to help and encourage its implementation;

- Publicise the nature of CCP sticks and carrots diplomacy, in order to alert businesses, academia and the public to the need for and reasons behind countermeasures;

- Coordinate with other free and open countries; exchange experience and jointly study CCP measures; seek to reform and shore up global governance, in particular the World Trade Organisation and standard setting organisations.

1.0 Introduction

Whether or not the People’s Republic of China (PRC) will become the 21st century’s economic centre of gravity, it will nevertheless be an important power. British policymakers rightly plan to maximise good relations; the challenge is to set the balance between cooperation and defence of the United Kingdom’s (UK) holy trinity of security, values and prosperity.

George Osborne’s policy of the ‘Golden Era’ made the golden error of ignoring the nature of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and mistaking its intentions. The current government has recognised the need for a reset of relations. The divergence of political, economic and values systems between the CCP and free and open countries is growing – in some areas pushed by Beijing. At the same time, extensive decoupling from the PRC would be costly, given the deep intertwining of supply chains, the benefits of open trade and investment regimes, and the pursuit of global goods such as climate change, preventing pandemics, peacekeeping and international development. The simplistic certainty of the ‘Golden Era’ has given way to a difficult age of balance.

In seeking that balance, it does not help that many exaggerate the benefits to be gained from uncritical cooperation with the PRC and the costs suffered from asserting British security, values and prosperity. Exaggeration is understandable in the case of the CCP, whose external propaganda machinery is geared to convincing others that the PRC’s rise is inevitable and irresistible – ‘the east is rising, the west is declining’ in Xi Jinping’s oft-used phrase. It is less acceptable when it comes from UK entities whose narrow interests are served by going along with the CCP narrative (for example, ex-ministers and senior civil servants who retain influence with ex-colleagues and whose consultancy companies are engaged by Chinese companies). In between are the uncritical journalists, businessmen, politicians and policymakers, who treat as orthodoxy statements that CCP retaliation is ‘ruinous’1Richard Lloyd Parry, ‘American can’t refight the Cold War in Asia’, The Times, 26/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3qHuMQc (found: 01/07/2021). or warn against the ‘pressure from sinophobes’ and ‘commit[ting] harakiri’.2James Sassoon, ‘Britain can ill afford to turn its back on China’, The Telegraph, 08/06/2020, https://bit.ly/3jGT23p (found: 01/07/2021).

The CCP’s foreign policy is largely built upon economic sticks and carrots, not upon shared values, cultural influence, or even military power – to say nothing of alliances. The implicit – and sometimes explicit – inducement/threat is that, unless the UK supports the Chinese narrative, it will suffer in six areas:

- Exports;

- Chinese investment in the UK;

- The financial and associated services of the City of London;

- The number of Chinese students at British universities;

- Tourist visits; or,

- Cooperation over climate change.3‘The Times view on coronavirus, Taiwan and 2021: China Rising’, The Times, 01/02/2021, https://bit.ly/3wdaSxF (found: 01/07/2021).

Yet, while it is true that the CCP can inflict gain or pain – and has done to a number of countries – the effects have often been exaggerated. The PRC is not immune to the effects of disrupting economic and commercial flows; it has important needs in all the areas supposedly threatened. The CCP is not a charity favouring benighted economies. Xi’s new ‘dual circulation’ policy puts greater emphasis on Chinese domestic markets, innovation and industry, but it is nevertheless ‘dual’, and the reliance upon the rest of the world in the six areas listed means that not cooperating with democratic countries would come at an unacceptably high price to the CCP.

Seeing clearly the balance of advantage, the costs to both the PRC and the UK in the six areas is crucial to proper policymaking, and not just in those areas, but more widely. If the threat to exports or investment is not as great as assumed, then Her Majesty’s (HM) Government is freer to decide policy on such things as fifth-generation (5G) telecommunications, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, nuclear energy without having to look over its shoulder.

That is the contention of this Report: the CCP’s sticks and carrots are neither as threatening nor as juicy as generally portrayed, whether for Britain or for other countries which have been or are being targeted. But let HM Government research these areas and come to its own conclusions – perhaps it is already doing so, although that is not apparent (as it does so, if it entrusts research to outside bodies, it should take care that they are uninfluenced by the CCP, which goes to increasing lengths to interfere abroad).

Two other points are worth noting. This Report considers relations with the PRC under ‘normal’ conditions. If divergence between free and open countries and the PRC were to descend to decoupling and a degree of hostility, but still short of war, the CCP might try to bring pressure to bear through measures more akin to economic warfare than the current sticks and carrots policy, for example through its domination of certain resources and supply lines (as it did with rare earths and Japan in 2010 – although not successfully, because Japan diversified). Reacting to overt coercion is a different matter to that considered here. It does however make sense for HM Government to prepare for such a contingency.4James Rogers, Andrew Foxall, Matthew Henderson and Sam Armstrong, ‘Breaking the China Supply Chain: How the “Five Eyes” Can Decouple From Strategic Dependency’, Henry Jackson Society, 05/2020, https://bit.ly/3we8N4o (found: 01/07/2021). Secondly, it is right to refer to the CCP and not China when discussing relations. China is run by a Leninist party and Xi himself continually stresses that the CCP leads everything.

2.0 China is different – and becoming more so

China is different. All countries’ foreign policies push their own interests, and all countries’ foreign policies are an extension of their domestic concerns. But China’s foreign policy is the foreign policy of the CCP – the interests pushed are primarily its interests, the ambitions and values reflected are those of the CCP. These differ very considerably from those espoused elsewhere, including in the Soviet Union and now Russia. At times they are also at variance with the interests of the Chinese people.

Sheer size is another difference. Free and open countries like the UK have not hitherto had to deal with an economic power of the PRC’s size and system. Nor have other countries been so consistent and unified in their foreign relations, in the sense that the CCP does not allow a variety of Chinese players to operate independently in their own fields. ‘The Party leads everything’ means that it is ever-present whether in cultural, commercial, academic, military, sporting, legal or other areas of relations. All Chinese entities, including businesses, must acknowledge ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy’, even if the CCP cannot in practice oversee all their activities and deal making.

Furthermore the difference is widening. The PRC is not like the Soviet Union in the Cold War. The UK rightly does not seek to decouple from the PRC: the Chinese economy is heavily intertwined with the rest of the world. But the degree of divergence is increasing, not just in political and values systems, but also in economic systems. Internally, if not in external propaganda, the CCP is clear about this: in his first Politburo speech in January 2013, Xi spoke about a tough struggle in which Chinese socialism had ‘to gain the dominant position over western capitalism’.5See: Tanner Greer, ‘Xi Jinping in Translation: China’s Guiding Ideology’, Palladium, 31/05/2019, http://bit.ly/xjitcgi (found: 24/03/2021). In ‘Document No. 9’ of April 2013, the party explicitly declared off limits the values upon which liberal democracies are built.6‘Document 9: A ChinaFile Translation’, ChinaFile, 08/11/2013, https://bit.ly/2P94ok0 (found: 01/07/2021). For every external mention of ‘win-win’ or ‘a community of shared future for mankind’ there are multiple internal repetitions of ‘struggle’ and ‘hostile foreign forces’. Cooperation should be pursued with the PRC, but only with wide open eyes and with a clear recognition of the limits.

3.0 The nature of CCP diplomacy and foreign relations

Being a major power in foreign relations depends on a blend of cultural, ideological, military power and what the CCP calls ‘discourse power’ (话语权 / huayuquan) – loosely, the ability to set the terms of or influence global governance – but above all economic power. The PRC has this last; the others are work in progress – or even in regress, for example in propagating its values.

Beneath the rhetoric the reality is that the CCP uses economic sticks and carrots to pursue its interests. The message to other countries is clear, if unspoken: align with Chinese/CCP interests and you will be allowed to share in prosperity; displease, and you will be excluded from what is to become the world’s biggest economy.

Two other elements complete what has been allowed to become a successful troika of methods. The first is external propaganda work, to which CCP devotes very considerable resources.7‘China is spending billions on its foreign-language media’, The Economist, 14/06/2018, https://bit.ly/2NMogsm (found: 01/07/2021). The ‘sticks and carrots’ approach is backed up by a drumbeat centred relentlessly on messages such as ‘the rise of the CCP is inevitable and irresistible’ and ‘the east (China) is rising, the west is declining’ (东升西降 / dong sheng, xi jiang).

The second element is the ‘united front strategy’, set by the United Front Work Department (UFWD), but featuring in the evaluation objectives of all Chinese officials. Following the lead of Mao Zedong, who declared the UFWD to be one of the three ‘magic weapons’ (along with the CCP itself and the People’s Liberation Army), Xi has reinforced the united front system. Essentially, the united front strategy divides others into the enemy, the neutral and the friendly. It seeks to isolate the main enemy, and to move other potentially hostile entities to a neutral, or preferably a friendly, state. The main enemy is the United States (US). The UK is to be rendered neutral, if not friendly. The strategy is implemented through a series of actions on a spectrum ranging from acceptable influence (public diplomacy) to unacceptable interference and economic pressure.

While the Propaganda Department seeks to influence from outside, the united front tries to mobilise resources from within its target. Its first port of call has traditionally been the overseas Chinese community and their various associations. But it also buys into the political and business elites; supports what used to be known as ‘fellow travellers’; puts pressure on academics in China-related fields; uses the unthinking, who merely repeat material fed to them; and feeds the anxieties of business whose eye is fixed on their share price or quarterly results.8The author was told in 2019 by one prominent businessman whose company derives large profits from its business in the PRC that ‘we just have to roll over and accept it all.’ The important point for policymakers is to be sure that the advice they receive from outsiders is filtered for bias and vested interests.

However unsuccessful the CCP has been in promoting its norms and values,9Laura Silver, ‘China’s international image remains broadly negative as views of the U.S. rebound’, Pew Research Centre, 30/06/2021, https://pewrsr.ch/3jHVTsO (found: 01/07/2021). when it comes to sharp elbow power – convincing many in the UK and other countries that it is too costly to go against Chinese interests – it has done well.

3.1 Creating policy without propaganda

Not succumbing to the ‘China’s inevitable rise’ propaganda is essential if policymakers are to approach relations with the PRC guided by realism, and not by the CCP. Three issues, among others, are important:

- It is by no means a given that the PRC will be the superpower of the twenty-first century. Nevertheless its size means that it will remain an important power. The PRC’s economic rise may not be sustainable, mainly because the governance model may not be sufficient to deal with the challenges of demographics, debt, water scarcity in the north, and finally childcare and education problems, which mean that it will be difficult to sufficiently improve the quality of the workforce.10Charles Parton, ‘The Challenges Facing China’, The RUSI Journal, 165:2 (2020). See also: Natalie Hell and Scott Rozelle, Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2020). Nevertheless, it will be a power, unless one subscribes to a theory of collapse, which would certainly not be in the UK’s or the world’s interest.11Gordon G. Chang, The Coming Collapse of China (London: Arrow, 2003).

- The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) does not exist: it is a slogan – and a very successful one. The March 2015 ‘Action Plan’ is a statement of aspirations, not a plan.12‘Visions and actions on jointly building Belt and Road’, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic South Africa, 30/03/2015, https://bit.ly/3hd091P (found: 01/07/2021). Talk of investment of trillions of dollars, ‘China’s Marshall Plan’, the signing of countless memoranda and agreements, and much more build the propaganda myth. What is real is Chinese globalisation (the ‘Action Plan’ has four other elements besides infrastructure with which the BRI is usually associated: global governance, trade facilitation, financial integration and people to people relations). Concrete projects should be the focus, not mythmaking.

- British politicians have talked about Brexit allowing the UK the freedom to negotiate free trade agreements (FTA).13‘Boris Johnson: UK should have its own free-trade agreement with China’, The Guardian, 18/10/2013, https://bit.ly/3hsornu (found 01/07/2021). See also: David Davis, ‘Trade deals. Tax cuts. And taking time before triggering Article 50. A Brexit economic strategy for Britain’, ConservativeHome, 14/07/2016, https://bit.ly/3xdsPgJ (found: 01/07/2021). The value of FTAs with the PRC is debatable: those struck by other countries tend to be shallow in content. Some argue that to offend the Chinese would jeopardise a FTA.14‘Great Britain cannot be “Great” without independent policies toward China: Chinese envoy’, Global Times, 16/08/2020, https://bit.ly/3dBHtH5 (found: 01/07/2021). This is scaremongering or unthinking – for the simple reason that there will not be one within ten years, if ever. The European Union (EU) chose to negotiate an investment agreement before a FTA because it was more simple; yet the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment took eight years to negotiate and may not now be ratified. Australia took ten years to agree a FTA, and even then it was pushed through for political rather than trade reasons, something Canberra may regret now in the light of the CCP’s riding roughshod over normal practice as it seeks to ‘punish’ Australia. It is refreshing to see that a UK minister has at last recognised openly that a FTA is not on the cards.15Nigel Adams, ‘Oral Evidence: Xinjiang detention camps’, House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, 04/27/2021, https://bit.ly/3ykHeb0 (found: 01/07/2021).

4.0 The CCP’s levers of power

The list of countries which the CCP has put in the diplomatic doghouse is lengthening. In line with the united front strategy, the CCP has not openly sought to use the measures below on the main enemy US (although some of its companies have been threatened), but rather on its allies and friends. In the recent past members of the kennel club have included Norway (2010-2016), Japan (2010-2012), UK (2012-2014), the Philippines (2012-2016), Mongolia (2016-2017), Taiwan (2016), South Korea (2016-2017), Canada (2018-present) and Australia (2018-present).16Peter Harrell, Elizabeth Rosenberg and Edoardo Saravalle, ‘China’s Use of Coercive Economic Measures’, Centre for a New American Security, 06/2018, https://bit.ly/3ApSYuG (found: 01/07/2021).

The reasons are varied, but centre around two themes: either countries are perceived by the CCP as having gone against its ‘core interests’, or their policies are too proximate to those of the US. Australia is a special case and perhaps represents the need for an assertive CCP to ‘kill a chicken to scare the monkeys’. In 2020, Cheng Jingye, the Chinese Ambassador to Australia, sent to his hosts a list of fourteen offences.17Jonathan Kearsley, Eryk Bagshaw and Anthony Galloway, ‘If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy: Beijing’s fresh threat to Australia’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3wg3Xnn (found: 01/07/2021).

In 2010, Dai Bingguo, then PRC State Councillor in charge of foreign affairs, gave a serviceable definition of ‘core interests’, namely:

China’s form of government and political system and stability. Second, China’s sovereignty, territorial integrity and national unity. Third, the basic guarantee for sustainable economic and social development.18Dai Bingguo, ‘Dai Binguo, State Councilor of China: Persist in taking the road of peaceful development’ (‘中国国务委员戴秉国:坚持走和平发展道路’), Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国中央人民政府), 06/12/2010, https://bit.ly/3h9ZP43 (found: 01/07/2021).

Thus Norway, which was blamed for awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to human rights defender Liu Xiaobo, offended under the first heading. Under the second, for questioning PRC sovereignty and territorial integrity in the form of challenges to Beijing’s claims to islands in the East and South China seas, are Japan and the Philippines; for threatening national unity, by their leaders meeting the Dalai Lama, the UK and Mongolia became targets; and Taiwan threatened the CCP’s aim of gaining control over the island.

South Korea’s deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) missile system meant that it moved too close to US interests in CCP eyes. The same may be said for Canada, whose arrest of the Chief Finance Officer of Huawei in compliance with an American extradition request in December 2018 could also be seen as an attack on the PRC’s economic development, since Huawei, even though in theory a private company, is a major plank in the CCP’s push to dominate global telecommunications.

Finally, Australia might be said to have offended under all three categories. Not only are its offences manifold, but it seems to have been selected as a middle level power out of whom to make an example.

4.1 The political bark

Particularly since Xi declared the three ages of the PRC, which ‘has stood up, become rich and is becoming strong’ CCP diplomacy has become ever more assertive, and at times overbearing.19Tom Phillips, ‘Xi Jingping heralds “new era” of Chinese power at communist party congress’, The Guardian, 18/10/2021, https://bit.ly/3xduX8d (found: 01/07/2021). When another country transgresses the CCP’s interests, its Propaganda Department ensures that official media and its paid influencers on internet platforms run through an established playbook on a sliding scale of aggression. In the UK’s case the admixture usually includes accusations of harking back to an imperial past, colonialist attitudes or ‘Cold War mentality’, or ‘offending the feelings of the entire Chinese people’. Meetings of foreign politicians and ministers with their Chinese counterparts are then postponed without an appointed date for resumption or cancelled. Thus, Australia’s annual bilateral strategic and economic dialogue with the PRC has not been held since 2017,20A formal declaration of a moratorium on the dialogue was announced in May 2021. See: ‘Statement of the National Development and Reform Commission on the indefinite suspension of all activities under the China-Australia Strategic Economic Dialogue Mechanism’ (‘国家发展改革委关于无限期暂停中澳战略经济对话机制下一切活动的声明’), National Development Reform Commission (国家发展和改革委员会), 06/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3qJ4pJR (found: 01/07/2021). and there have been no ministerial conversations since April 2020.21Bill Birtles et al., ‘China denies Australian minister’s request to talk about barley amid coronavirus investigation tension’, ABC News, 18/5/2021, https://ab.co/3hiu0WZ (found: 01/07/2021). Eventually political relations are put into the deep freeze until the foreign country repents of its behaviour, for example by agreeing not to invite the Dalai Lama in future (UK and Mongolia) or recognising the CCP’s core interests (Norway).22From Norway’s statement on the normalisation of bilateral relations: ‘The Norwegian Government reiterates its commitment to the one China policy, fully respects China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, attaches high importance to China’s core interests and major concerns, will not support actions that undermine them, and will do its best to avoid any future damage to the bilateral relations.’ See: ‘Statement of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Kingdom of Norway on normalisation of diplomatic relations’, Government of the Kingdom of Norway, Undated, https://bit.ly/3wibbHj (found: 01/07/2021).

The political bark is often more successful than it should be. British ministers set great store by the importance of their visits, perhaps because they look more to their domestic profile than to concrete results of such exchanges. Diplomats are fully aware that the claims of billions of pounds or dollars of business are greatly exaggerated by including deals already signed, or deals under discussion but which will never be signed. A good example was the £40 billion of Chinese trade and investment claimed as a result of the visit of Xi to the UK in 2015.23Heather Stewart and Phillip Inman, ‘David Cameron’s “£40bn raised from Chinese visit” claim under scrutiny’, The Guardian, 23/10/2015, https://bit.ly/3yjYvl0 (found: 01/07/2021). Visits and contacts are important, but ministers should realise that they are icing, not cake. Australian trade with the PRC is holding up well, despite a Chinese ban on ministerial contacts since 2018.24Peter Hartcher, ‘China’s latest move a mere formality as Xi and Morrison speak the dialogue of the deaf’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 06/5/2021, https://bit.ly/3w7OuFW (found: 01/07/2021).

4.2 The economic bite

There are five economic areas perceived as vulnerable to CCP pressure – exports, investment, financial services and the City of London, students, and tourism. In addition, Chinese cooperation over climate change has been spoken of as contingent upon not offending the CCP.25For example, see The Times’ editorial of 2nd Jan 2021: ‘But Beijing must not be allowed to manipulate the West in return for notional concessions at the COP26 conference this year.’ See: ‘The Times view on coronavirus, Taiwan and 2021: China Rising’, The Times, 02/01/2021, https://bit.ly/3wdaSxF (found: 01/07/2021). A consideration of the six areas suggests that concerns are overdone.

5.2.1 Exports

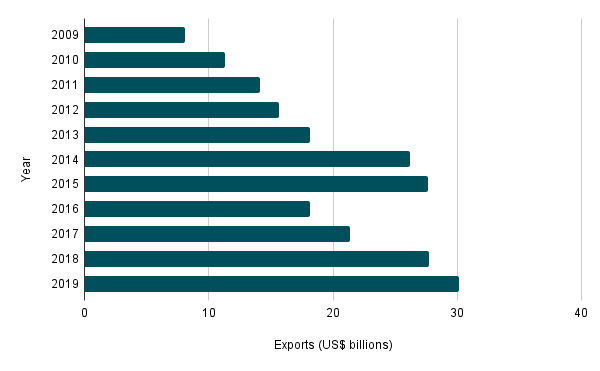

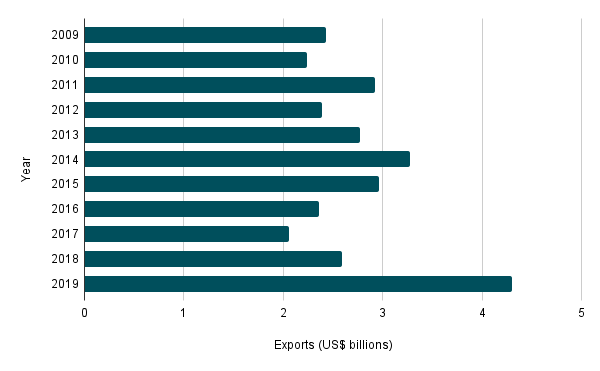

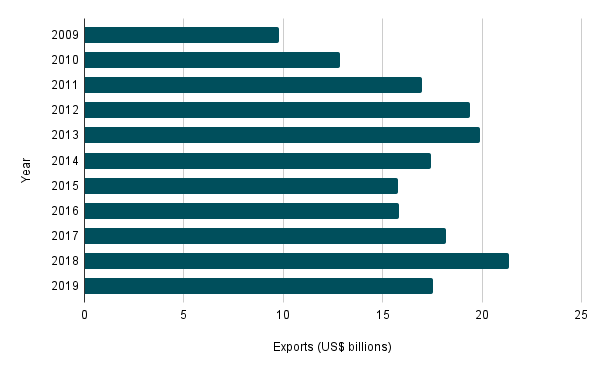

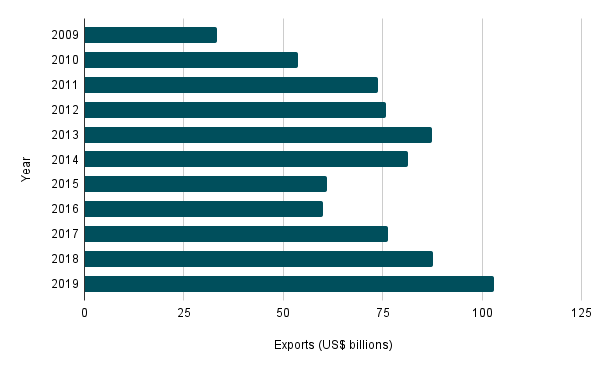

Overall export performance. Most countries put in the diplomatic doghouse by the PRC saw their exports rise during that time (dates in brackets are those when relations were bad):

UK (2012-2014):26‘United Kingdom Exports to China in US$ Thousand 2009-2019’, World Integrated Trade Solution, 2021, https://bit.ly/3As93jA (found: 01/07/2021).

Norway (2010-2016):27‘Norway Exports to China in US$ Thousand 2009-2019’, World Integrated Trade Solution, 2021, https://bit.ly/2SNdVit (found: 01/07/2021).

South Korea (July 2016-October 2017):28‘Korea Exports to China in US$ Thousand 2009-2019’, World Integrated Trade Solution, 2021, https://bit.ly/3hgmewz (found: 01/07/2021).

Canada (December 2018-present):29‘Canada Exports to China in US$ Thousand 2009-2019’, World Integrated Trade Solution, 2021, https://bit.ly/3dIIZHb (found: 01/07/2021).

Australia (2017-present):30‘Australia Exports to China in US$ Thousand 2009-2019’, World Integrated Trade Solution, 2021, https://bit.ly/2TyGu3v (found: 01/07/2021).

Ignoring 2020 because of the impact of Covid-19, the graphs show that for all countries trade grew in the years of bad relations, with one exception: Canada in 2019. This is likely to be the result of a cut back in agricultural exports, which has now been reversed (see below for how cereals suffer for one season, but rarely longer). While Norway saw decreases in 2015 and 2016 compared to earlier years, so did the other countries (for the UK 2015-2016 was the start of the ‘Golden Era’, while South Korea, Australia and Canada had yet to fall foul of the CCP). Other – non-political – factors appear to have been at play.

Displacement trade is important. In a globalised world it is not uncommon that when the PRC switches its buying from one country to another, third countries take up the slack, ensuring that after a period of disruption the cost to the targeted country is not great. Thus, as Graph 1 shows, although the PRC turned elsewhere for its fish, other countries helped to maintain the overall growth in Norwegian fish exports.31See: ‘Norwegian salmon export value up 7% in 2019’, Fishfarming Expert, 07/01/2020, https://bit.ly/3hxWrik (found: 01/07/2021).

Graph 1: Norwegian fish exports from 2009-2019

The same applies to Australian barley. The imposition of 80.5% tariffs led to a fall in exports, which has since been reversed with nearly all export surplus sold, largely by redirecting exports to Saudi Arabia.32Masha Belikova, ‘Saudi demand leaves 2-mo of Australian barley exports left’, Fastmarkets Agricensus, 21/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3wgR0cU (found: 01/07/2021). And while there has been much talk of the damage inflicted on Australia’s coal exports, the reality is that displacement trade has largely deflected losses.33Rebecca Le May, ‘Aussie coal still finding its way to China through other markets’, News.com.au, 15/01/2021, https://bit.ly/3sl1FlP (found: 01/07/2021).

Where does the PRC try to inflict pain using economic sticks? Firstly, and unsurprisingly, the PRC does not hit hard import sectors essential to its own economy. Thus, in the Australian case, because the PRC cannot access iron ore of the quality and price, that trade has continued unaffected – at increased world prices, much to China’s cost. Again, the 2021 quota for importing Australian wool has increased (strangely New Zealand’s remained the same as for 2020, despite Wellington’s avoidance of clashes with Beijing).34‘China increases import quota for Australian wool’, Global Times, 01/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3fcvZvi (found: 01/07/2021).

Export sectors which the CCP targets fall under three headings:Ketian Vivian Zhang, ‘Chinese non-military coercion – Tactics and rationale’, Brookings, 22/01/2019, https://brook.gs/3wi5nxB (found: 01/07/2021).

- Goods which can be easily sourced elsewhere or are not essential. Examples include Australian wine and lobsters, or Korean cosmetics, music and entertainment, and supermarkets (the Lotte supermarket chain was hit because it sold the land upon which THAAD missiles were deployed, but this move also benefitted Chinese competitors).

- Goods which are symbolic, such as Norwegian salmon (Norway’s global exports of fish in 2011 fell by less than 0.1% compared to 2010; they fell a further 0.2% in 2012 before regaining a steady climb).Of course, no ban was ever announced by the CCP; instead, it used increased veterinary inspections as the excuse to ban Norwegian fish imports.35See: Mark Godfrey, ‘Norwegian salmon exporters feel China’s wrath’, Seafood Source, 28/05/2012, https://bit.ly/2UkS4ze (found: 01/07/2021). For statistics, see: ‘Norwegian salmon export value up 7% in 2019’, Fishfarming Expert, 07/01/2020, https://bit.ly/3hxWrik (found: 01/07/2021).

- Agricultural produce. This is deliberately disruptive for a season as farmers find other export outlets or change crops. The CCP is aware that it often arouses powerful farming lobbies to put pressure on their governments. But bans, effected often by dubious use of phytosanitary customs regulations are also short-lived, not least because China has a food security problem and must import to feed its population. Thus, American soybean farmers were briefly targeted; restrictions on Canadian pork, beef and canola oil lasted only a season and now Canada finds demand for canola is emptying its reserves.36Marcy Nicholson, ‘China is buying up so much Canadian canola that traders fear a looming shortage’, Financial Post, 02/05/2021, https://bit.ly/36d4Pi2 (found: 01/07/2021).

How significant is the damage? It would be wrong to suggest that no price is paid by individual companies or by sectors when countries defend their security, values and economic interests against CCP aggression. Australian wine producers have lost a big market. So did the South Korean music and entertainment industry, although given the ideological and nationalistic turn now taken by the CCP towards a culture that was inevitable in the longer run. It is also difficult to make a counterfactual estimate of how great exports might have been, had the CCP not imposed measures to limit them.37Ivar Kolstad, ‘Too big to fault? Effects of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize on Norwegian exports to China and foreign policy’, Chr. Michelsen Institute, 2016, https://bit.ly/3hmfjCh (found: 01/07/2021). For the UK, CCP threats have hinted at measures aimed at pharmaceutical and automobile manufacturers.38‘“Great Britain” cannot be “Great” without independent policies toward China: Chinese envoy’, Global Times, 16/8/2020, https://bit.ly/3dBHtH5 (found: 01/07/2021). A more recent form of attack has been the mobilisation of Chinese consumers to boycott the products of foreign companies which offend, for example over use of cotton from Xinjiang whose production may use slave labour.39Linda Lew, ‘China presses global fashion brands to reverse Xinjiang cotton boycott’, South China Morning Post, 25/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3hD9NK8 (found: 01/07/2021).

The question for British policymakers is: what price are you prepared to pay for the UK’s security, values and prosperity? The answer needs to take into consideration the limited, if high profile, nature of the goods which the CCP targets, the speed of offsetting through displacement trade, and the temporary nature of Chinese measures, particularly in the agriculture/food sector. It needs to close its ears to CCP propaganda and the siren voices who declare that thousands of jobs linked to exports to the PRC are at risk. While exports to the PRC are estimated to support around 55,000 full time jobs, they would not all be at risk if the UK defies the CCP.40China Britain Business Council, ‘UK jobs dependent on links to China’, UKinbound, 22/07/2020, https://bit.ly/3hFE9vQ (found: 01/07/2021). Exports will not plummet from 2019’s £30.7 billion to zero.41‘United Kingdom Exports to China in US$ Thousand 2009-2019’, World Integrated Trade Solution, 2021, https://bit.ly/3dJ7kNg (found: 01/07/2021). Trade for most goods will carry on regardless of the political storms, as long as UK companies produce goods which the PRC wants, needs and cannot produce for itself, and as long as price and quality are right. The Government needs to articulate these points clearly to consumers and producers, who may bear the brunt of the (limited) CCP measures.

It is never wise for any business to be too dependent upon one customer, however convenient or well-paying. Undoubtedly, British companies should diversify their export customers. It would also be sensible to note that the CCP’s emphasis on Xi’s updated version of Mao’s ‘self-sufficiency’ (自力更生 / zi li geng sheng) and the ‘dual circulation’ policy, which are interlinked, aim to cut out foreign suppliers where possible. On the positive side, the failure of the CCP to bring Australia to heel through application of the economic stick may perhaps lead it to reconsider the strategy in the long term. Unity of reaction to pressure among other free and open countries might serve to reinforce this conclusion. Furthermore, inflation is a perpetual worry for the CCP (it was a major factor in the unrest in 1989) and some of the measures being taken against other countries will be costing the Chinese economy – or consumers – large amounts. For example, one Canadian company reports its price for coking coal as US$100 per ton higher than Australian product; its exports in Quarter 1 of 2021 were up 22%, meaning that if all that was due to the Australia ban, the PRC was paying an extra US$130 million for the coal from that one company.42Hector Forster, ‘Teck, US coking coal miners continue to reap China premium on Australia coal ban’, S&P Global Platts, 29/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3ArXclJ (found: 01/07/2021).

Clearly when politics mixes with trade everyone loses. But the picture emerging from a dispassionate look at the past shows that the losses are small and limited to a narrow range of sectors.

4.2.2 Investment

The stick and carrot are deployed with no great subtlety. Thus, the UK decision on 5G telecommunications in the words of Lui Xiaoming, then Chinese Ambassador to the UK, ‘undermined the confidence of Chinese businesses in making investments in the UK’.43‘“Great Britain” cannot be “Great” without independent policies toward China: Chinese envoy’, Global Times, 16/8/2020, https://bit.ly/3dBHtH5 (found: 01/07/2021). He also declared that ‘a more confrontational stance toward China will inevitably dampen bilateral economic cooperation prospects, such as a possible delay or suspension of talks between China and the UK on free trade talks and mutual investments’.44‘UK undermines trust with China, may ruin FTA talks’, Global Times, 26/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3jIuQ0w (found: 01/07/2021).

The message, broadcast by Chinese officials and relayed, and often exaggerated, by interested or uncritical UK parties,45‘The China Dividend Two Years In’, Manchester China Forum, 09/2018, https://bit.ly/3ys5GaN (found: 01/07/2021). is that Chinese investment is large, essential to the UK’s future economic well-being and contingent upon wider British cooperation with CCP aims. It is a picture not confirmed by reality.46Michael Pettis, ‘Does the UK Benefit From Chinese Investment?’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 05/06/2019, https://bit.ly/3wr5tTX (found: 01/07/2021).

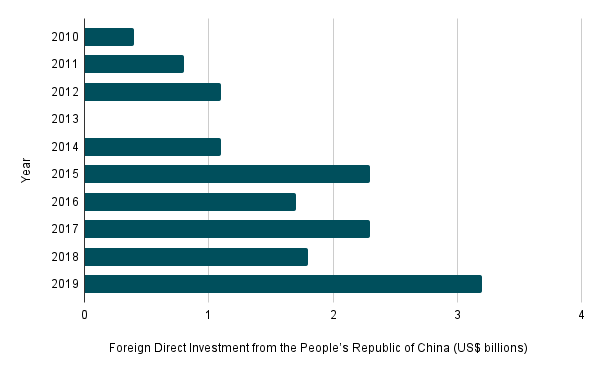

In terms of the UK’s overall stock of investment, the Chinese share is just 0.2%.47‘Trade and Investment Factsheets’, Department for International Trade, 18/06/2021, https://bit.ly/2SMJSax (found: 01/07/2021). Although the UK has been the biggest European recipient of Chinese investment, since 2016 Xi has instituted a severe tightening of investment abroad, away from sectors such as property, entertainment and football clubs. This is reflected in the statistics for the UK: as Graph 2 shows, after growth in 2017 (a lag from 2016), investment fell sharply, although there was a slight rise in 2019 over 2018, when weakness in sterling will have increased the attraction of investment here.

Graph 2: Foreign Direct Investment from the PRC 2010-2019

There are further reasons why Chinese investment in the UK may not return to the level of five years ago. The Chinese economy is slowing. Under Xi’s ‘dual circulation’ policy the emphasis on investment is domestic facing where possible. Increasing divergence between China and the liberal democracies will narrow the areas where the UK and other countries are willing to countenance Chinese investment (the National Security Investment Act was passed in April 2021).

The four major reasons for welcoming foreign investment hardly apply to Chinese investment in the UK. The first myth is that the UK needs a rich PRC’s money. The price of money is very cheap at present, with interest rates at historic lows; money is plentiful for good projects. A second reason for welcoming investment is to gain new technology. Chinese investment brings none. On the contrary, the flow is in the other direction: a major motive for Chinese investment is to get hold of British technology. A third is to learn new management techniques (Japanese ‘just in time’ delivery and other management techniques greatly helped the British automobile industry). Again, the flow is from the UK to the PRC.

Lastly, a major boon of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is the creation or safeguarding of jobs. Here there have been gains, but small ones. It is difficult to think of a Chinese greenfield site in the mould of Honda or Nissan. Indeed this is not specific to the UK: throughout Europe only a very small percentage of Chinese FDI is linked to greenfield sites.48Agatha Kratz et al., ‘Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 Update’, Merics, 08/04/2020, https://bit.ly/3hFEKh4 (found: 01/07/2021). According to the Department of International Trade, the number of jobs created or safeguarded by Chinese investment in the three years of 2016/7 to 2018/9 was 9,400 of which 1,700 were in the third year (i.e., a decreasing number).49Matthew Haynes et al., ‘UK jobs dependent on links to China’, China-Britain Business Council, 07/2020, https://bit.ly/3hgrOPJ (found: 01/07/2021).

It is also worth noting that this investment is not charity. The Chinese authorities have sought to concentrate investment in sectors which directly benefit their modernisation and ambitions, particularly to make up for its gaps in technology, innovation and branding. The new focus is on sectors the CCP wishes the Chinese economy to dominate in the future: pharmaceuticals and health, specialised industries, agriculture – and above all technology.50Jamie Nimmo and Robert Watts, ‘How Beijing brought up Britain’, The Times, 02/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3heQE2c (found: 01/07/2021). This applies particularly to state owned firms. While much recent investment has come from private and not state owned companies,51Agatha Kratz et al., ‘Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 Update’, Merics, 08/04/2020, https://bit.ly/3hFEKh4 (found: 01/07/2021). and while private companies are freer to pursue investment which suits their interests, they too will have an eye to the CCP’s new focus. And economic/technological needs will continue to trump any political urge to punish.

In sum, when it comes to investment the benefits of Chinese investment in the UK should not be exaggerated. Nor should they be dismissed, where such investment is in sectors which benefit both countries, and as long as proper controls are in place to protect against Intellectual Property (IP) theft, transfer of dual civilian-military technology, or the promotion of instruments useful to the CCP for refining its repression apparatus. Just as British companies invest overseas for reasons of self-interest, so China does the same in the UK, and will continue to do so. If political relations become strained, the CCP will cancel or postpone a few high-profile investments in order to apply propaganda pressure, but the overall harm is likely to be limited, and may fall harder on Chinese interests.

What about UK FDI in the PRC?

Although the focus of most politicians has been on Chinese investment into the UK, the question of the UK’s outward investment into the PRC is relevant. In terms of Britain’s overall FDI stock, investment in the PRC is small: the PRC accounted for 0.7% (£10.7 billion) of the UK’s total global stock in 2019.52‘Trade and Investment Factsheets’, Department for International Trade, 18/06/2021, https://bit.ly/2SMJSax (found: 01/07/2021).

The direction of future trends is hard to predict. Current CCP policies suggest that risks for investing companies are increasing, whether geopolitical, to data and IP, or from the CCP’s ‘dual circulation’ strategy, or indeed from consumer boycotts organised on the internet and indirectly encouraged by the CCP’s nationalistic propaganda. Divergence, or in the worst case decoupling, may also make investment less attractive.

But many of the considerations relevant to inbound investment also apply to outbound. The CCP is likely to select some targets for disruption where they have a high political profile in the UK. But the generality of investment will be left alone, where China needs the technologies and skills brought in by foreign companies.

4.2.3 Financial services and the City of London

In 2020 the UK exported £5.1 billion of services to the PRC, with a surplus of £3.1 billion.53Ibid. To put this in context, the PRC is not among the top ten destinations for services exports.54Abi Casey, ‘UK trade in services by partner country: July to September 2019’, Office for National Statistics, 22/01/2020, https://bit.ly/3ADtGts (found: 01/07/2021). It still accounts for only 0.4% of the total of financial services exports55‘The UK as an International Financial Centre’, TheCityUK, 06/2019, https://bit.ly/3hxn8Uh (found: 01/07/2021). (financial services, along with insurance and pensions, account for just over 10% of services exports).56Matthew Ward, ‘Statistics on UK trade with China’, House of Commons Library, 14/07/2020, https://bit.ly/2P8d5Lb (found: 01/07/2021).

In the eyes of some this ‘indicat[es] great potential for future growth’.57‘The UK as an International Financial Centre’, TheCityUK, 06/2019, https://bit.ly/3hxn8Uh (found: 01/07/2021). But just as in the 1980s the ‘wall of Japanese money’ did not arrive, so it may prove in the 2020s with Chinese money. There are several reasons for this. The first lies at the policy level. The CCP, which recognises, and in some areas encourages, divergence with free and open countries, has a shrinking desire to be beholden to them. Its ideal is to service its needs through financial and other centres in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hong Kong. As Lui Xiaoming, the former Chinese Ambassador to the UK, said:

Take a look at world history…no major country achieved national prosperity without a foundation of considerable financial power…Therefore, China must build a strong financial sector if it is to achieve national revitalisation.58Liu Xiaoming, ‘Remarks by HE Ambassador Liu Xiaoming at the opening of ICBC Standard Bank’, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United Kingdom, 02/02/2015, http://bit.ly/rbhealxatooisb (found: 01/07/2021).

Cooperation in services is fine, but should be carried out with a clear recognition that Chinese organisations wish to learn and then repatriate as much business activity as possible.

Secondly, hopes for the development of export services centre on the ‘stock connect’ between the London stock market and Shanghai’s, on the City of London’s role in the internationalisation of the Chinese yuan and on raising money for BRI. These hopes do not look robust. So far only two stocks have been listed on the ‘stock connect’ programme.59Yujing Liu, ‘China approves second listing for Shanghai-London Stock Connect amid strained Sino-British ties’, South China Morning Post, 03/06/2020, https://bit.ly/3jIbM2z (found: 01/07/2021).

Internalisation of the yuan may be a very long time coming. The PRC must first run external deficits or permit unrestricted outward movement of capital, as well as improve trust through the rule of law. These factors would require major political change, which the CCP is not prepared to countenance. It is therefore hard to see the yuan, which currently has around 2% of market share, increasing dramatically.

The upshot of the above is that, while the UK and the City of London should strive to increase the export of services to the PRC, it is not the case that El Dorado lies just beyond the horizon. This in turn means that threats need not be considered as potent as the CCP and some British interested groups have portrayed (for some the threats are worrying, such as HSBC or Standard Chartered, which derives a large percentage of its profits from Asia. The UK government must decide to what degree it will allow HSBC to set its policy on the PRC).

This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that where the Chinese economy does need to import services, the UK and the City of London have some considerable advantages. This means that punishing Britain for policy misdemeanours becomes more costly and difficult. The UK’s performance in the services sector is a wider question than just China; it concerns global competition, the effects of Brexit and maintaining London’s advantages over the long term. Even so, in the case of the PRC, two of London’s competitors may suffer from political handicaps: New York City because of the struggle between the US and the PRC, and Hong Kong because the CCP is throttling the trust in ‘One Country, Two Systems’, in particular its legal system. UK benefits include being well placed in between Asia and America; the English language; a trusted and efficient legal system (the English language greatly helps here too); high-quality regulators and a strong regulatory regime; an abundance and concentration of trained talent (although it can move over time); the proximity of other services which mutually reinforce each other; a good education system for families; and being a pleasant and safe place to live.60See: ‘Agricultural Bank of China – the international banking group’, The Global City, 2021, https://bit.ly/3dKBuzL (found: 01/07/2021) and Cecily Liu, ‘ABC establishes first branch in London’, China Daily, 27/06/2018, https://bit.ly/3hgnXlx (found: 01/07/2021).

The result is that to the extent that the Chinese economy requires services from abroad, London will remain the likely destination for considerable business, even if on occasions deals will be lost in order to make a propaganda point.

4.2.4 Students and universities

The UK education sector has developed a dependency on Chinese students, particularly at the university level. In 2018/9 120,000 attended, making up 25% of foreign students and 5% of all students.61‘International student recruitment data’, Universities UK, 2020, https://bit.ly/3jINOV2 (found: 01/07/2021). Fees amounted to over £2 billion,62Rosemary Bennett, ‘Chinese pay 25% of fees at Russell Group universities’, The Times, 23/07/2020, https://bit.ly/3hgHhzb (found: 01/07/2021). and student expenditure excluding fees was just under £2 billion, supporting over 17,000 jobs throughout a three-year period.63Matthew Haynes et al., ‘UK jobs dependent on links to China’, China-Britain Business Council, 07/2020, https://bit.ly/3hgrOPJ (found: 01/07/2021). According to the Chinese embassy, as a result of US visa restrictions in 2021 the number of students in the UK has risen to 216,000.64Lou Kang, ‘216,000 Chinese students study in UK as a result of US visa restrictions’, Global Times, 20/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3ym1s4j (found: 01/07/2021). Australia’s relatively strict Covid-19 entry restrictions may also have played a role.

However, it is never a good idea in any industry (academics may wince at the term) to be overdependent on one supplier. In the long-term Chinese demographics will restrict the supply, while in the shorter term a severe downturn in the Chinese economy might have a painful effect. But the threat of the CCP curtailing numbers for political reasons has been exaggerated.

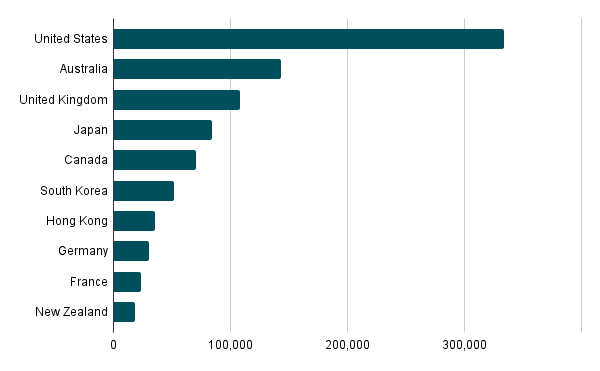

Demand remains vibrant.65‘CCG Releases Annual Report on the Development of Chinese Students Studying Abroad (2020-2021)’, Centre for China and Globalisation, 02/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3ApfT9E (found: 01/07/2021). Chinese who can afford it want their one child educated abroad. In 2019 703,500 Chinese studied overseas, a rise of 6.25% over 2018.66‘Statistics of Chinese learners studying overseas in 2019’, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 16/12/2020, https://bit.ly/3qSVcyv (found: 01/07/2021). Overwhelmingly, they want their child educated in an English-speaking country with a good education system. That means the US, Australia, the UK and Canada, with a smaller number in New Zealand – as it happens, the countries which make up the ‘Five Eyes’ intelligence grouping, so often vilified by the CCP. In the event of a political attack by the CCP on the UK, the rise in Chinese student numbers may cease or reverse. But the difference is unlikely to be great, not least because Britain’s fellow anglophone competitors are likely to continue to enjoy poor relations with Beijing.

Graph 3: Chinese students’ preferred destinations in 201967‘Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students’, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2019, https://bit.ly/3yorAeO (found: 01/07/2021).

Might Xi, who talks of education as ‘engineering the soul’, just as Joseph Stalin did, forcibly curtail study abroad? It seems unlikely that he would risk offending the middle classes. This would be a formidable group if it turned against the CCP, which is itself very conscious that beneath its undoubted popularity stability is fragile. Why else does the CCP spend more on domestic surveillance and repression than on external defence and security, and insist that the People’s Liberation Army and the People’s Armed Police are not national forces but belong to the CCP? Xi can encourage Chinese parents to send their child to countries other than the ‘big four’ and they will react against whichever of those countries is the whipping boy of the day, but overall, the threat is smaller than many presume.

Britain’s universities have benefitted from considerable Chinese research funding. That is not animated by lofty ideals or charity, but is motivated either by Chinese research needs or by a desire to influence. The excellence of UK universities reduces the threat of moving such funding elsewhere. It is another, and important, debate as to which areas of research should be open to Chinese funding, given security concerns over the CCP’s long term geopolitical ambitions.

4.2.5 Tourism

The same applies to CCP threats to reduce Chinese tourist numbers68Wang Jiamei, ‘Australia’s economy cannot withstand “Cold War” with China’, Global Times, 10/06/2020, https://bit.ly/3hz4POB (found: 01/07/2021). – something achieved with far greater effectiveness by Covid-19, which makes it hard to judge the reality behind the threats. Certainly in the past the CCP has used turning the tourist tap off to put pressure on countries which have displeased it. Taiwan arrivals fell from a 2015 high point of 4 million to 3 million in 2017 and thereafter, although overall foreign visitor numbers grew throughout.69Isabella Steger, ‘China tried to threaten Taiwan by weaponizing tourism, but it didn’t work’, Quartz, 07/01/2020, https://bit.ly/3dHEa18 (found: 01/07/2021). South Korea suffered a 40.6% drop.70Jung Suk-yee, ‘Number of Chinese Tourists Visiting South Korea Drops after China’s Travel Ban’, BusinessKorea, 12/11/2019, https://bit.ly/3qK3EAb (found: 01/07/2021). In both cases and that of the Philippines, the CCP was able to put pressure on package tours.

In normal times the UK is a favoured tourist destination, given its history and the high opinion in which the country is held by ordinary Chinese (second to France out of 36 countries with a 81% attractiveness rating).71Alison Bailey, ‘A new era: towards a soft power strategy for the UK in China’, 11/2020, https://bit.ly/2TzNrkS (found: 01/07/2021). The important difference with those countries geographically close to the PRC which have been affected by tourist bans is that 88% of Chinese tourists to the UK are individuals, not package tourists.72‘China’, VisitBritain, 2020, https://bit.ly/3ylpfBj (found: 01/07/2021). Administratively it would be difficult for the CCP to limit the destinations of private tourists via travel companies and airlines. Tourism is the opiate of the (middle class) masses. To ban them from visits to the UK or offending countries would be a brave move, not least because on top of the travel they enjoy the opportunity for ‘daigou’ (buying on behalf of others, usually luxury goods at reduced prices abroad for resale inside the PRC).73Cheryl Heng, ‘How Chinese professional shoppers, or daigou, operate – by buying luxury goods for less overseas and shipping them for customers in China’, South China Morning Post, 25/09/2020, https://bit.ly/36eUW3e (found: 01/07/2021).

4.3 The green kowtow

Some have advanced the view that liberal democracies cannot afford to offend the CCP, because they need the PRC’s help in combating climate change. For example, this is the assumption lying behind a 2nd January 2021 editorial in The Times, which talks of persuading the CCP to cut emissions, and of Beijing not being allowed ‘to manipulate the West in return for notional concessions at the COP26 conference this year’.74‘The Times view on coronavirus, Taiwan and 2021: China Rising’, The Times, 02/01/2021, https://bit.ly/3wdaSxF (found: 01/07/2021). The implication of this is that the UK will need to modify its policy towards the PRC in other areas in order to secure cooperation on climate change. Others have attacked the CCP for insincerity, because even as it talks about the need to cooperate on climate change, the use of coal-fired power stations in the PRC and their export to developing countries is rising.75Hanna Barczyk, ‘China’s climate sincerity is being put to the test’, The Economist, 19/06/2021, https://econ.st/3ApgtEm (found: 01/07/2021). Both approaches are misguided. There are good reasons why the CCP has both political and economic motives for being serious about tackling carbon emissions. As ever, the determination of the centre to order change meets the realities of implementation at the provincial and city level. This is not a tanker which can be turned around quickly.

Evidence of the seriousness with which the CCP approaches climate change comes both from recent international exchanges and from domestic considerations. Despite increasingly bitter disagreement over Xinjiang, Hong Kong, the South China Sea and more, the CCP has unilaterally come out with a commitment to peak emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.76Matt McGrath, ‘Climate change: China aims for ‘carbon neutrality by 2060’, BBC News, 09/22/2020, https://bbc.in/3wim2kw (found: 01/07/2021). Xie Zhenhua, the Chinese Special Envoy for Climate Change had a productive meeting with his American counterpart in April 2021.77‘US-China Joint Statement Addressing the Climate Crisis’, US Department of State, 17/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3ylKpiT (found: 01/07/2021). That month amidst sanctions mutually imposed between the PRC and Europe over Xinjiang, Xi joined Angela Merkel and Emmanual Macron to discuss climate change.78Finbarr Bermingham, ‘Macron and Merkel hope climate talks with Xi can help take sting out of China-EU tensions’, South China Morning Post, 16/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3xju4Lp (found: 01/07/2021). Xi has set store by the PRC becoming a global leader in this area. He is unlikely to set aside that ambition.

All countries will suffer from climate change, but by numbers and size of effect none will match the PRC. Among other concerns are greater flooding and droughts, exacerbation of the water scarcity problem in north China, food security as crop yields fall, and the threat of submergence of coastal regions as sea levels rise (the Shanghai region is particularly vulnerable).79See: ‘Which sea level will we lock in?’, Climate Central, 2019, https://bit.ly/3Alv83k (found: 01/07/2021) and Hu Yiwei, ‘Why sea level rise is a big deal for China’, CGTN, 08/13/2019, https://bit.ly/2UskAPG (found: 01/07/2021). The CCP is well aware of this and the threat it poses to its economic, social and political order, upon which its legitimacy is largely based. Failure to tackle climate change would lead to instability and a threat to the CCP’s hold on power.

This means that withholding cooperation on climate change is not an option and need not worry UK policymakers as they react to CCP behaviour in other areas.

5.0 Conclusion

HM Government needs to be clear eyed about the nature of the CCP and its aims: divergence is here to stay; Xi’s doctrine of greater self-reliance means cutting out foreigners where possible; there is no inclination to grant a ‘level playing field’ for foreign business, and non-tariff and other trade barriers to preserve existing advantages will continue; a FTA in any meaningful timescale is illusionary; ‘win-win’ is a slogan covering a CCP addiction to ‘struggle’. HM Government should be equally clear that this is not going to change, unless the CCP is swept away in revolution – an unlikely prospect.80Roger Garside, China Coup (Oakland: University of California Press, 2021). Rather it accords with the nature of the CCP; there is little in its one hundred year history to convince otherwise. Nor is this exclusively about Xi’s personality or style of leadership; many of today’s policies began before he came to power. He has merely accelerated and deepened existing trends and tendencies. Democratic countries have finally realised that globalisation will not lead to democratisation in the PRC.

Defying the CCP is never without pain, whose infliction is an integral part of its diplomacy. But that is no reason for exaggerating its potency. CCP action falls well short of its bellicose statements. Business people will still do business, investors invest, students study, and tourists tour as long as prices, quality and conditions are right. The sky has not fallen in because Britain decided that allowing Huawei to build its 5G telecommunications was a threat to security. Certainly, in purely financial terms, it may increase costs, but security does cost – and some measures are more effective and considerably cheaper than nuclear missiles. Meanwhile Australia, which has offended in fourteen more serious ways, continues to increase its exports to the PRC year on year since 2015.81‘Australia’s trade in goods with China in 2020’, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 03/09/2020, https://bit.ly/3hCKRT0 (found: 01/07/2021).

It is also worth considering the price inflicted on Britain’s values and way of life by continually giving way to CCP bullying and bribery. The divergence in values between the CCP and the UK, as well as other free and open countries, should be clear by now.82Charles Parton, ‘UK Relations with China’, China Research Group, 02/11/2020, https://bit.ly/2UqymC1 (found: 01/07/2021). Acquiescence and appeasement are a slippery slope; they would require the UK to change its aspiration from being the global leader envisioned in the Integrated Review of March 2021, to being a global follower. If through short-term fear of CCP reaction HM Government does not protect sensitive research and intellectual property, it will prejudice Britain’s long-term security and ability to say ‘no’ to bigger future demands. Not asserting British sovereignty opens the door to interference in Britain’s politics, media, universities and freedom of speech.83See: Charles Parton, ‘China-UK Relations: Where to Draw the Border Between Influence and Interference?’, RUSI Occasional Paper, 20/02/2019, https://bit.ly/3Ata5fh (found: 01/07/2021). This is not merely abstract. It means being forced to buy clothes made from cotton produced with slave labour; or students not being able to write their theses on topics deemed off-limits by the CCP (the author is aware of at least two recent cases, where British supervisors refused to help doctoral students); or fears on the part of politicians, journalists, academics, business people, of being sanctioned by the CCP.84‘Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Announces Sanctions on Relevant UK Individuals and Entities’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’ s Republic of China, 26/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3wh9tpQ (found: 01/07/2021). These threats may in some cases change present and future behaviour, since the sanctions will be extended to organisations employing the sanctioned. Politicians might, for example, become more supportive of CCP preferences if defiance meant missing out on lucrative jobs after their time in office.

Restoring a balance to relations requires HM Government to have a clear and detailed strategy for the PRC. That did not emerge from the Integrated Review; one hopes that it is work in progress, to appear shortly.85Charles Parton, ‘China in the Integrated Review’, Britain’s World, 19/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3clsh0x (found: 01/07/2021). Another requirement is coordination in dealing with the CCP, both within government, between government and the rest of society, and with other liberal democracies. But the starting point is for policymakers and politicians – but also the rest of society – to have a clear-eyed view of CCP behaviour, to realise that decisions can be made without worrying unduly about CCP sticks and carrots, but rather with a gimlet eye fixed upon Britain’s security, values and prosperity. British policymakers should ‘seek truth from facts’, not from propaganda and vested interests.

5.1 Recommendations

Disagreements between ministers over Huawei’s involvement in the UK’s 5G telecommunications system made clear the need for a strategy for dealing with the PRC, which is agreed and implemented across all government departments. Without one it will be difficult to counter unacceptable CCP influence on British policy.86See: Charles Parton, ‘Towards a UK strategy and policies for relations with China’, The Policy Institute, 06/2020, https://bit.ly/3rhp4TY (found: 01/07/2021) and Sophia Gaston and Rana Mitter, ‘After the Golden Age’, British Foreign Policy Group, 07/2020, https://bit.ly/39b4q1g (found: 01/07/2021). As part of drawing up such a strategy, HM Government would do well to:

- Carry out or commission research – before publishing it – on the six areas of threat/inducement (including both inward and outward investment), ensuring that it is not influenced by CCP or its united front supporters, or done by those unfamiliar with CCP ways.

- Increase the powers of the China National Strategy Implementation Group (NSIG) to coordinate and ensure the implementation of a consistent government-wide policy towards the PRC.87For a detailed look at this recommendation, see: Alexi Drew, John Gerson, Charles Parton and Benedict Wilkinson, ‘Rising to the China challenge’, The Policy Institute, 07/01/2020, https://bit.ly/3hgtUiz (found: 01/07/2021).

- Work out essential supply lines, resources, goods where the UK must be independent of the PRC.

- Be ready to provide temporary financial support to help diversification of exports where the CCP decides to inflict temporary economic losses; to explain the need for diversification to both business and academia; and to help and encourage its implementation.

- Publicise what the CCP is doing in its sticks and carrots diplomacy, in order to alert businesses, academia and the public to the need for and reasons behind countermeasures. Where the CCP behaves egregiously outside international norms or law, it should be called out. It is however important that the tone is measured to avoid the CCP manufacturing indignation and thereby diverting attention from the substance of the issue.

- Coordinate with other free and open countries; exchange experience and jointly study CCP measures; seek to reform and shore up global governance, in particular the World Trade Organisation and standard setting organisations.

About the author

Charles Parton OBE is a James Cook Associate Fellow in Indo-Pacific Geopolitics at the Council on Geostrategy. He spent 22 years of his 37-year diplomatic career working in or on China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. In his final posting he was seconded to the European Union’s Delegation in Beijing, where, as First Counsellor until late 2016, he focussed on Chinese politics and internal developments, and advised the European Union and its Member States on how China’s politics might affect their interests. In 2017, he was chosen as the Foreign Affairs Select Committee’s Special Adviser on China; he returned to Beijing for four months as Adviser to the British Embassy to cover the Communist Party’s 19th Congress.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank John Gerson and Raffaello Pantucci for their comments on previous drafts of this paper. He would also like to thank Achishman Goswami, the Charles Pasley Intern at the Council on Geostrategy, for his assistance with research and formatting.

Disclaimer

This publication should not be considered in any way to constitute advice. It is for knowledge and educational purposes only. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Council on Geostrategy or the views of its Advisory Council. Any conclusions drawn from data included in this publication are the responsibility of the author and not that of the issuing body.

No. SBIR01 | ISBN: 978-1-914441-01-1

- 1Richard Lloyd Parry, ‘American can’t refight the Cold War in Asia’, The Times, 26/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3qHuMQc (found: 01/07/2021).

- 2James Sassoon, ‘Britain can ill afford to turn its back on China’, The Telegraph, 08/06/2020, https://bit.ly/3jGT23p (found: 01/07/2021).

- 3‘The Times view on coronavirus, Taiwan and 2021: China Rising’, The Times, 01/02/2021, https://bit.ly/3wdaSxF (found: 01/07/2021).

- 4James Rogers, Andrew Foxall, Matthew Henderson and Sam Armstrong, ‘Breaking the China Supply Chain: How the “Five Eyes” Can Decouple From Strategic Dependency’, Henry Jackson Society, 05/2020, https://bit.ly/3we8N4o (found: 01/07/2021).

- 5See: Tanner Greer, ‘Xi Jinping in Translation: China’s Guiding Ideology’, Palladium, 31/05/2019, http://bit.ly/xjitcgi (found: 24/03/2021).

- 6‘Document 9: A ChinaFile Translation’, ChinaFile, 08/11/2013, https://bit.ly/2P94ok0 (found: 01/07/2021).

- 7‘China is spending billions on its foreign-language media’, The Economist, 14/06/2018, https://bit.ly/2NMogsm (found: 01/07/2021).

- 8The author was told in 2019 by one prominent businessman whose company derives large profits from its business in the PRC that ‘we just have to roll over and accept it all.’

- 9Laura Silver, ‘China’s international image remains broadly negative as views of the U.S. rebound’, Pew Research Centre, 30/06/2021, https://pewrsr.ch/3jHVTsO (found: 01/07/2021).

- 10Charles Parton, ‘The Challenges Facing China’, The RUSI Journal, 165:2 (2020). See also: Natalie Hell and Scott Rozelle, Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2020).

- 11Gordon G. Chang, The Coming Collapse of China (London: Arrow, 2003).

- 12‘Visions and actions on jointly building Belt and Road’, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic South Africa, 30/03/2015, https://bit.ly/3hd091P (found: 01/07/2021).

- 13‘Boris Johnson: UK should have its own free-trade agreement with China’, The Guardian, 18/10/2013, https://bit.ly/3hsornu (found 01/07/2021). See also: David Davis, ‘Trade deals. Tax cuts. And taking time before triggering Article 50. A Brexit economic strategy for Britain’, ConservativeHome, 14/07/2016, https://bit.ly/3xdsPgJ (found: 01/07/2021).

- 14‘Great Britain cannot be “Great” without independent policies toward China: Chinese envoy’, Global Times, 16/08/2020, https://bit.ly/3dBHtH5 (found: 01/07/2021).

- 15Nigel Adams, ‘Oral Evidence: Xinjiang detention camps’, House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, 04/27/2021, https://bit.ly/3ykHeb0 (found: 01/07/2021).

- 16Peter Harrell, Elizabeth Rosenberg and Edoardo Saravalle, ‘China’s Use of Coercive Economic Measures’, Centre for a New American Security, 06/2018, https://bit.ly/3ApSYuG (found: 01/07/2021).

- 17Jonathan Kearsley, Eryk Bagshaw and Anthony Galloway, ‘If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy: Beijing’s fresh threat to Australia’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3wg3Xnn (found: 01/07/2021).

- 18Dai Bingguo, ‘Dai Binguo, State Councilor of China: Persist in taking the road of peaceful development’ (‘中国国务委员戴秉国:坚持走和平发展道路’), Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国中央人民政府), 06/12/2010, https://bit.ly/3h9ZP43 (found: 01/07/2021).

- 19Tom Phillips, ‘Xi Jingping heralds “new era” of Chinese power at communist party congress’, The Guardian, 18/10/2021, https://bit.ly/3xduX8d (found: 01/07/2021).

- 20A formal declaration of a moratorium on the dialogue was announced in May 2021. See: ‘Statement of the National Development and Reform Commission on the indefinite suspension of all activities under the China-Australia Strategic Economic Dialogue Mechanism’ (‘国家发展改革委关于无限期暂停中澳战略经济对话机制下一切活动的声明’), National Development Reform Commission (国家发展和改革委员会), 06/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3qJ4pJR (found: 01/07/2021).

- 21Bill Birtles et al., ‘China denies Australian minister’s request to talk about barley amid coronavirus investigation tension’, ABC News, 18/5/2021, https://ab.co/3hiu0WZ (found: 01/07/2021).

- 22From Norway’s statement on the normalisation of bilateral relations: ‘The Norwegian Government reiterates its commitment to the one China policy, fully respects China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, attaches high importance to China’s core interests and major concerns, will not support actions that undermine them, and will do its best to avoid any future damage to the bilateral relations.’ See: ‘Statement of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Kingdom of Norway on normalisation of diplomatic relations’, Government of the Kingdom of Norway, Undated, https://bit.ly/3wibbHj (found: 01/07/2021).