Liz Truss, the new British Prime Minister, is beginning a premiership at a time of considerable challenge. Inflation, a likely recession, an energy crisis, and a strained health service will limit her agency for the next few months. As a candidate, Truss has stood out for prioritising economic growth and deregulation over fiscal conservatism. But achieving long-term increases in growth, particularly beyond low-value services, will require a clear-eyed assessment of the United Kingdom’s (UK) relative weaknesses.

There is widespread acknowledgment that Britain’s current trajectory is not sustainable and points to stagnation. After years of de-industrialisation and ‘over-financialisation’, there is an appetite to reshore manufacturing supply-chains and increase domestic energy production. This is part of a wider aspiration to be a technology and science ‘superpower’. It is a worthy aspiration, but currently, only one of the many missions Her Majesty’s (HM) Government is undertaking. ‘Net Zero’ – transitioning to a low carbon economy by 2050 – demands the Government spend billions on renewable-led electrification. ‘Levelling-up’ – promoting prosperity in peripheral regions of the country – entails reducing regional inequality by making deprived areas more competitive. There has been a broad push for free-trade agreements to steer the UK towards our comparative advantage in services. And geopolitical challenges lead to calls for increased military spending.

In some cases, these missions are synergistic. Allocating increased public research funding to the Midlands through increased investment would assist in levelling up while also promoting reshoring. Military spending increases, like other forms of public sector procurement, can prioritise British manufacturing. But in other ways, they might be antagonistic. Net Zero and free-trade agreements could inhibit the UK’s manufacturing competitiveness in the short term – thereby hindering those businesses that invest in research the most. Increasing renewables might be laudable, but the UK’s degraded industrial capacity means most turbines and some panels are manufactured elsewhere.

There is a need for pro-industry cadres to coordinate re-industrialisation at the levels of business, politics, and government.

These competing objectives are being pursued against the backdrop of an ageing population where the extension of average life expectancy has slowed to a standstill. Based on the findings of the British migration observatory, this dejuvenation has not been successfully mitigated even by massive increases in immigration. Ageing exacerbates budgetary pressures caused by a significant and growing trade and current account deficit. In summary, HM Government has too many missionary frameworks with competing objectives and a demographic profile that increasingly constrains government resources needed to achieve those objectives.

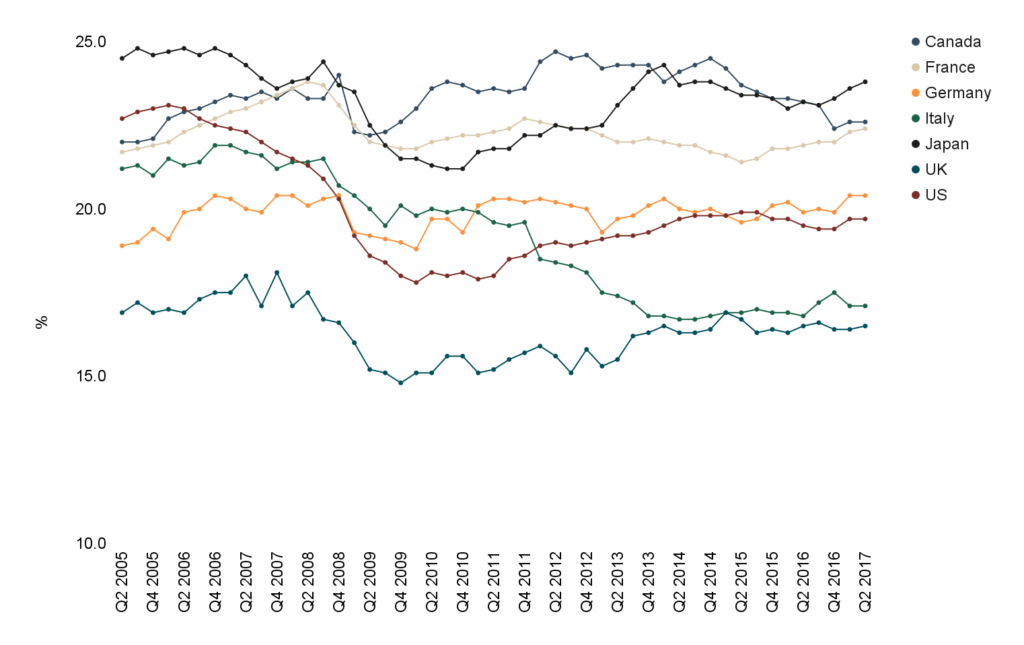

There is one factor that makes all these missions harder: poor productivity growth – particularly in manufacturing. A key part of this slump is the UK’s uniquely low capital formation as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (See: Chart 1).

Chart 1: Gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of gross domestic product between Group of Seven (G7) nations

Low capital investment translates into low investment in research & development – where the UK is last amongst G7 countries. Even government targets for improving this metric for 2027 would only bring Britain in line with the OECD average. It is not just about the amount of money. Research allocation is dysfunctional and should be prioritised for reform. These macroeconomic trends manifest in the real economy through reduced deployments of machines and technology in the public and private sectors.

End the UK’s laggard status in automation

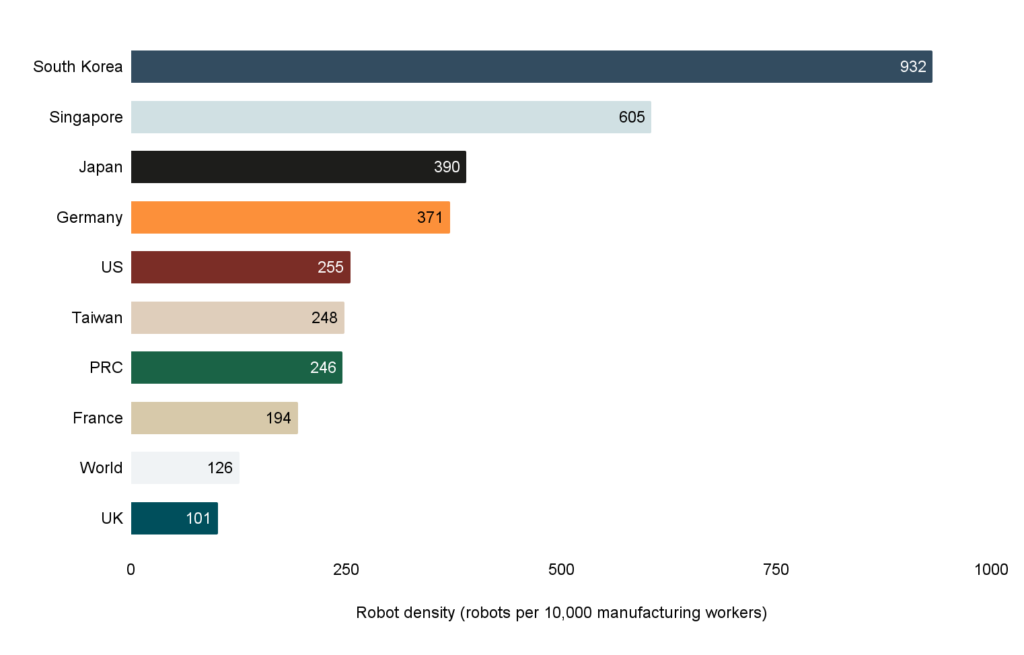

Industrial robotics is one space where Britain is actually below the world average (See: Chart 2). Robots are critical for increasing output in a constrained labour market and improving productivity. The UK’s failure to keep up on this key metric makes our industries less competitive compared to those of other countries. This, far more than automation, is to blame for the loss of manufacturing employees across the country. This can be seen in the precipitous decline in British car manufacturing over the last five years.

Chart 2: Robot density (robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers) for 2020

Increasing the UK’s robot density rate is critical to increasing productivity and addressing labour shortages. The British ecosystem is notably better in non-industrial fields of robots, for example, Milton Keynes has proven to be an excellent testing ground for mobile delivery robots used for ferrying groceries and takeaways across suburban spaces. But testing and piloting are a tiny part of the value in the supply chain. In terms of gears, drives, sensors, semiconductors, and the operational software that makes robots work, Britain’s profile is negligible. The UK’s robot density rate (currently 101 robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers) should be targeted to exceed the world average (126) in two years and be competitive with Sweden (289) in five years.

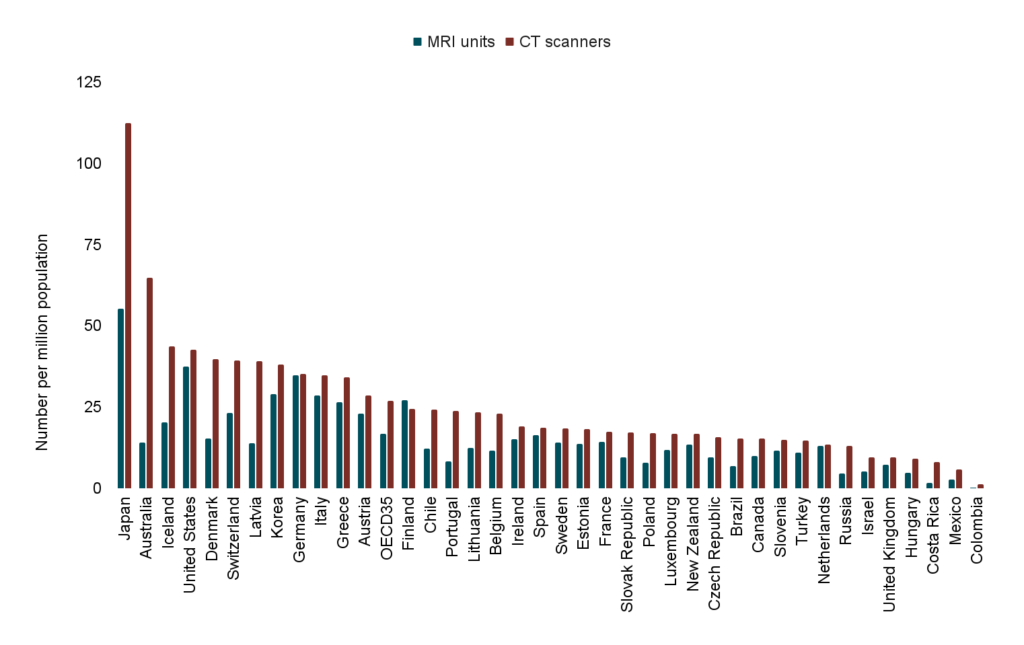

The lack of machines applies not merely to robots. The National Health Service has fewer computerised tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners per capita than any major European economy – or Turkey, Brazil, Russia or Chile for that matter (See: Chart 3).

Chart 3: CT and MRI devices per million population

Physical automation is the best corporate tool available for mitigating high labour prices. Research has shown companies that automate at a greater and faster rate are more competitive and as a result hire more workers. The United States, which previously tracked Britain in low adoption of robots, is now automating at a record rate with a density over twice that of the UK. Britain has a tiny profile in terms of adoption numbers, companies, and patents – with notable exceptions like Ocado. The need to improve this situation is definitive. Any concerns about mass joblessness are at this point discredited. Large meta-studies have found a minimal or positive correlation between automation and employment.

Truss has affirmed her commitment to ending decades of stagnation. Achieving this will depend on prioritising capital investment in new equipment and increasing electricity production.

More self-reliance in electricity production

Productivity-led growth through more machines is energy-intensive and will require a lot more energy – particularly electricity. An industrial robot consumes 21,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) per year. The average British household consumes 3,800 kWh. Combined with the demand for electric vehicles, we should be seeing a rise in electricity production. But the trajectory of the UK since 2000 has been from becoming an energy exporter to a major importer. The country crucially is producing far less electricity, just as it embarks on the wholesale electrification of the economy. Increases in variable renewables have not filled the drop in electricity generation from coal or nuclear. While there have been efficiency improvements, a greater factor in Britain’s declining energy production is attributable to the decline of energy-intensive industries replaced by both imports of finished goods and imports of electricity. Electricity imports via undersea cables, almost 10% of overall consumption, have grown more than solar photovoltaics. Much of these imports come from nuclear-heavy France. The last quarter has seen Britain export more electricity, primarily due to the Russian invasion, failures at French nuclear plants, and Britain’s temporary glut of liquified natural gas. But the yearly trend has been towards more imports.

Increasing electricity dependence on Europe – a continent noted for its own dependence on Russia and the Gulf states – is detrimental to the UK’s energy security. While temporary surpluses are positive, they are the result of non-existent gas storage – meaning it had to go elsewhere. It is not certain that British exports in the summer will be reciprocated with European exports in the winter. Having a more equal balance of electricity trading with our European neighbours should be a priority.

Chart 4: Net electricity imports, 1990-2021

Britain’s production and consumption of electricity have declined markedly in recent years. Given our poor record in investment, this has led to an insufficient grid. Due to the planned establishment of data centres in West London, housebuilders have been told it could take until 2035 to get new developments hooked up to the electricity network because of limited capacity. Both cloud computing capacity and new homes are going to be essential to growth in the next 10 years.

The £130 billion spent on holding down household energy bills this winter will be a drag on the taxpayer for years. The UK can ill-afford another crisis given our financial predicament. Redundancy must take precedence over efficiency. To avoid another debilitating energy crisis and provide energy abundance for businesses, electricity production should be substantially expanded – with considerable government intervention if need be.

People will determine policy success

How might greater automation be engendered besides increased energy capacity? Supply-side reforms like full-expensing of capital equipment would help, and be a major improvement on the temporary and underwhelming super-deduction. It would, however, be initially costly and cause a political battle. Supply-side reforms only go so far. Demand will have to be expanded through either targeted procurement spending or import substitution. Before any such policies are implemented, they require the buy-in from experts, politicians, advisors, and civil servants who are willing to prioritise re-industrialisation over other considerations.

There is therefore a need for pro-industry cadres to coordinate re-industrialisation at the levels of business, politics, and government. One way to establish these cadres could be to take inspiration from the Japanese practice of ‘Shindanshi’. These are government-licensed systems integrators and consultants who work with the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry to install good business practices and technology adoption amongst small and medium-sized enterprises. As consultants, they could align business development with government targets to a better degree than traditional private consultants. This new cadre would also provide a degree of status and prestige for aspiring engineers who are more policy-minded.

Re-industrialisation is a multigenerational project that rests on institutional buy-in and commitment more than policy specifics. It is a huge challenge and success is uncertain. Funding such an endeavour means foregoing investment elsewhere – possibly even in defence. But with jeopardy comes opportunity. The UK did not achieve industrial excellence by doing what it had always done best, or without state direction. British mastery not just of innovation but of production was the force multiplier that turned the country into the first globe-spanning superpower. Today, Truss has affirmed her commitment to ending decades of stagnation. Achieving this will depend on prioritising capital investment in new equipment and increasing electricity production.

Rian Whitton is a researcher at Bismarck Analysis, where he advises on technology, energy, and institutions.

Join our mailing list!

Stay informed about the latest articles on Britain’s World

Dear Rian,

Thank you for this first class article.