Foreword

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) publication of the Revolution Space report earlier this year was a significant development in European thinking about space. The High Level Advisory Group which wrote it was indeed operating at a high level, and included two distinguished British contributors. It set out ambitious plans for Europe to develop capacities in space to match the United States or People’s Republic of China. That opens up a range of important questions which are identified in this useful assessment by Gabriel Elefteriu.

Could Europe develop the range of space capabilities proposed in the Revolution Space report? Would full autonomy with no foreign input slow it down so much that it fails to catch-up with the competition? What does ‘Europe’ mean in this context: is this going to be an European Union or ESA programme? These are questions of great significance to us in Britain. There are tricky trade-offs here which are skilfully analysed in this report.

ESA’s high level group wanted to prompt an open debate on these issues and this excellent assessment is an important contribution to that discussion.

– The Rt. Hon. Lord David Willetts FRS

Chair, UK Space Agency

Executive summary

- The ‘European Moonshot’ programme outlined by the High Level Advisory Group (HLAG) is an expensive space development initiative to expand European space power for strategic advantage, with economic and geopolitical benefits.

- While scepticism is amply justified, the geopolitical imperative underlying the proposal is new and powerful. If the proposal goes forward in some form, as it might, Britain will have to take a position.

- Europe’s space manufacturing base and technology portfolio are insufficient for the task; a feasible programme will either have to reduce ambition, or allow external (commercial) contributions.

- The insistence on strict ‘autonomy’ as a foundational principle is a fatal flaw that contradicts the programme’s own imperatives of speed, scale and competitiveness. A European Moonshot programme should instead be conceived as an open system, allowing international commercial and governmental participation.

- Speed is paramount if Europe is to stay competitive in relation to the United States (US) and the People’s Republic of China. A parallel rather than stepped/sequential approach to programme delivery is required.

- New contracting and management authorities for the European Space Agency (ESA) – similar to the US Space Development Agency – as well as a shift to a NASA-style commercial approach are vital to programme success.

- A number of new institutions and mechanisms should be considered as potential solutions to governance and financing challenges:

- A European Space Investment Corporation, to promote commercialisation and investment;

- A European Cis-Lunar Organisation, to own the relevant space assets; and,

- An ESA venture capital arm similar to Central Intelligence Agency’s In-Q-Tel.

- The optimal scenario is a ‘Moonshot’ programme that includes a limited set of ‘autonomous’ capabilities but is otherwise predicated on collaborative, commercial principles geared to growing the wider European space sector. This could also attract British interest.

1.0 Introduction

In March 2023 the European Space Agency (ESA)1Britain remains part of ESA which is not an EU agency. published Revolution Space,2‘Revolution Space’, European Space Agency, 23/03/2023, https://bit.ly/3qq1Eko (checked: 05/06/2023). a paper by a ‘High Level Advisory Group’ (HLAG) chaired by Anders Fogh Rasmussen that proposed a ‘revolutionary’ plan to secure European strategic autonomy in human spaceflight: the ability to send people and cargo to destinations in Earth orbit, the Moon and eventually beyond. This would involve building out an entire ecosystem of space assets and infrastructures, from rockets to capsules, space stations and lunar vehicles. It requires a dedicated programme similar in scope to America’s 1960s Apollo, and a roughly 25% increase in the ESA’s budget.

Rasmussen’s group justified the proposal on geopolitical and economic grounds. There is a clear-eyed acknowledgement of the strategic importance of space power in its own right, as an instrument of geopolitical influence; and of the future significance of the ‘cis-lunar’ (Earth-Moon space) economy. Europe is not only behind the United States (US) and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the key space capabilities, but risks losing touch completely with its competitors.

When faced with yet another European grand project, strong scepticism is justified. But if implemented, Revolution Space can radically transform Europe’s space sector. His Majesty’s (HM) Government and the United Kingdom’s (UK) space industry would need to decide on a response. The plan holds both opportunities and pitfalls for Britain. British industry and expertise are well suited to the task and can play an important role, boosting the UK space sector and increasing the nation’s space ambition. There is also the opportunity to reform ESA itself in the process, which is in Britain’s interest. On the other hand, the plan, as it stands, is too complex and the European record on delivering such projects is very poor. In addition there are a suite of political risks to be considered in view of the UK’s status as a member of ESA but not the European Union (EU).

This paper considers how the Revolution Space vision could translate into a credible proposition. It offers a framework for thinking through the main factors of success or failure. It also identifies a rough version of a European ‘Moonshot’ programme that appears optimal in the circumstances and that could be attractive to Britain as well.

2.0 Moonshot: The vision

The Revolution Space vision is as grand as it may credibly be imagined today.3Allegedly, a mission to Mars was briefly considered for inclusion in the report, but ultimately deemed as not credible. It speaks of no less than galvanising and revolutionising ‘the whole European economy, well beyond the space sector’. Most of the report is devoted to making the general case for a new European approach to space, calling for a major ‘mobilisation of resources’ in conjunction with a more competitive space-industrial landscape (through new commercial practices and procurement reform).

Perhaps the most important ‘success factor’ identified in Revolution Space is speed. The HLAG correctly judges that it is absolutely imperative for Europe to move quickly with a Moonshot programme. There is only a limited window of time to catch up with the US and PRC.

In practical terms, the HLAG outlines a breath-taking list of independent European capability objectives, effectively an end-to-end, Earth-Moon space infrastructure and transportation chain complete with:

- (Reusable) cargo and crew space vehicles to Low Earth orbit (LEO) and Moon orbit, including a ‘super heavy launcher’;

- ‘Commercial’ LEO station;

- Lunar crew lander; and,

- ‘Sustained’ European presence on the Moon.

Unlike the US and PRC, Europe has no existing or planned autonomous capabilities across any of these mission sets which will play a vital role in the development of the cis-lunar economy in coming years. So the list makes sense in theory, as a breakdown of what is required for retaining a major space power status in the 21st century.

Regarding the timescale, the HLAG report sets a benchmark of an ‘independent and sustainable European human landing on the Moon in 10 years’. From this, and in conjunction with some other analyses circulating within the European space community – which favour a strictly ‘stepped approach’ to building out these capabilities – one may infer the following schedule:

- Reusable cargo to LEO (International Space Station (ISS)) by 2030;

- Crewed version by early 2030s;

- Cargo and crew vehicles to Lunar Gateway (the NASA station) by mid 2030s; and,

- Lunar crew lander in the 2040s.

The very rough cost projections at the moment are on the order of €2 billion (£1.7 billion) per year (average) when the full programme is up and running. This spending would need to be sustained over some 15 years, thus giving an approximate total development cost of some €30 billion (£25.9 billion). Thereafter, yearly operating costs would be expected to be between €1 billion-€2 billion (£0.85-£1.7 billion) depending on the number of flights, and so on.

The HLAG report is inevitably strongly worded, highly aspirational and all-encompassing. It over-reaches and shocks – but this is its purpose. This prospective European Moonshot is not just a programme, it is a space development initiative with the strategic end purpose of building European space power. It must be judged accordingly, through a much wider lens that goes beyond programme architecture and looks at the associated institutional frameworks and solutions required to make it truly transformational.

With so many different factors at play across such a vast enterprise, how can the plan be evaluated? The following sections propose four tests that identify key problems as well as some solutions.

3.0 Is Moonshot industrially feasible?

Industrial capacity to sustain such a vast space project is the starting point for any discussion of a European Moonshot programme. There is no suggestion that such an endeavour requires a pre-existing technological and manufacturing base vast enough to accommodate the entire vision from the beginning. Today’s relatively limited capacity would be expected to expand once the initiative is greenlighted. But just how significant is the difference between today’s capacity and the end ambition of any programme version, particularly when the imperative of speed is considered?

The size of Europe’s upstream space sector workforce was 52,000 in 2021. The big four large industrial groups (Airbus, Thales, Safran and Leonardo) provide 59% of the total employment, with Europe’s main space manufacturing entities being Airbus Defence & Space (20% of the workforce), Thales Alenia Space (14%) and ArianeGroup (7%).4‘Eurospace Facts and Figures 2021’, ASD Eurospace, 16/07/2022, https://bit.ly/45GKr6B (checked: 05/06/2023). Second-tier or ‘midcap’ players include OHB (5%), GMV, Avio, Telespazio and RUAG. The approximately 400-500 small and medium-sized enterprises contributing to the European upstream space supply chain – many of them micro-enterprises – represented only 8% of the European space manufacturing workforce in 2021.5Ibid. The European NewSpace landscape includes under 100 notable companies – such as IceEye or Isar – and around 1,500-2,000 employees in total.

According to Eurospace, in 2020 the geographic distribution of the upstream manufacturing workforce was estimated at approximately: 17,000 in France; 10,000 in Germany; 5,000 in Italy; 4,000 each in Spain and Britain; 1,500 each in Belgium and the Netherlands; with the other European countries estimated in the hundreds or dozens.6‘Eurospace Facts and Figures 2020’, ASD Eurospace, 16/07/2021, https://bit.ly/43LTm4V (checked: 05/06/2023). The upstream sector was worth €8.6 billion (£7.4 billion) in 2021 but with a majority of sales tied to European institutional customers, and only some €3 billion (£2.6 billion) to the commercial market including exports.

Europe’s total space budget (EU and national) in 2021 was around €10 billion (£8.6 billion), of which some 60% was ESA-managed, 23% civil national, and 12% military national, with the rest spread between EU and Eumetsat.7‘Eurospace Facts and Figures 2021’, ASD Eurospace, 16/07/2022, https://bit.ly/45GKr6B (checked: 05/06/2023).

As a measure of industrial output, in 2020 the European space industry delivered 50 satellites over 100 kilograms (small, medium and large), with an average of around 30 small satellites per year over the past decade.8‘Eurospace Facts and Figures 2020’, ASD Eurospace, 16/07/2021, https://bit.ly/43LTm4V (checked: 05/06/2023).

A brief comparison with just one element of the US Artemis programme – the crewed capsule Orion – is instructive. Orion has cost US$20.4 billion (£16.5 billion) since work on it began in 2006;9‘The Cost of SLS and Orion’, The Planetary Society, No date, https://bit.ly/3ISbCkL (checked: 05/06/2023). producing a single unit (European Service Module (ESM) excluded) is expected to cost almost US$1 billion (£0.8 billion).10‘NASA Awards Lockheed Martin Contract For Six Orion Spacecraft’, Lockheed Martin, 23/09/2019, https://bit.ly/43mhSd3 (checked: 05/06/2023). The main contractor for the Crew Module is Lockheed Martin, with components supplied by hundreds of companies across the US, and with a number of NASA centres involved as well. The ESM is built by TAS and Airbus, but even for this the main and auxiliary engines are provided by NASA, with the final integration of the ESM taking place at Kennedy Space Centre.11‘Orion Reference Guide’, NASA, 10/11/2022, https://bit.ly/3NmSTAR (checked: 05/06/2023).

In its Moonshot endeavour, Europe starts from a very low industrial-capacity point compared to stated ambitions and to its rivals. The notion of launching an Apollo-type effort solely with Europe’s internal resources is not credible: accordingly, the programme will likely have to be recalibrated.

4.0 Is Moonshot accessible?

One approach that can help solve some of these problems is the use of international partnerships. These can unlock access to new sources of funding, technology and manufacturing capacity. Europe is currently deficient across all of these, certainly in relation to a Moonshot programme that seeks to move quickly. Non-European partners, whether the UK, US, Israel, United Arab Emirates, Australia or Japan, would have much to contribute either through their agencies or, most significantly, through their own commercial companies – if Europe’s Moonshot programme is set up to accommodate such involvement.

It is on this point where the Revolution Space vision seems to miss the mark. It underlines the cardinal importance of European space ‘autonomy’ to such a degree as to seemingly close off any serious discussion of meaningful partnerships. This is unwise because it condemns Europe to ‘reinvent the wheel’ at great cost across many component parts of a Moonshot programme, instead of acquiring some of those technologies through commercial partnerships.

A strict adherence to ‘autonomy’ – bordering on autarchy – is also unnecessary across the full breadth of the programme in the same way; there should be room for exceptions and calculated risk-taking in some areas of capability, for example when it comes to a LEO station or orbital refuelling. The question should be not how to ensure autarchy but how to mitigate political or commercial risks associated with certain levels of ‘dependence’ in specific components over a certain time period until European-grown solutions come online.

Instead of a closed, ‘autonomous’ vision, Europe should aim for an open system approach that allows allied and likeminded governments and private companies to participate in a carefully designed and efficient manner. This will not only reduce costs and advance the programme quickly, but it will also drive strong growth in the European space sector.

Finally, the diplomatic benefit of an open system approach cannot be understated. The Artemis Accords have broken new ground in terms of international space partnerships and now NASA has effectively adopted the idea of partnering as a core operating principle. Through its own Moonshot programme, Europe has a great chance of constructing its own partnership framework including with Indo-Pacific allies and partners, helping to project not just its regulatory power but also its geopolitical influence across the globe. The fact that Europe’s space capacity is so much smaller than that of the US is an opportunity to craft a novel and more balanced approach that quite a few other countries might find attractive.

5.0 Is Moonshot manageable?

Setting the right management and governance framework in place from the very beginning will be absolutely critical to success – and this ‘management vision’ will also provide a key metric by which the investment community will judge the viability of the entire enterprise. New approaches and structures will almost certainly be required, which is why the HLAG report correctly identifies the need for transforming and reforming (some of) the way in which Europe ‘does’ space. The issues can be grouped in two categories: those pertaining to the practical execution of the programme; and those related to the surrounding politics.

5.1 Programme management: ESA

It is important to recognise the sheer magnitude of HLAG’s proposed programme. It would require a 25-30% increase in ESA’s budget: a huge leap, considering that the 7% boost achieved at the 2022 ESA Council of Ministers meeting was thought a success. A single Programme Office will likely be needed, in order to ensure coherence across all the different components, especially if – as this Policy Paper would suggest – a parallel build approach is adopted instead of the stepped one that is the HLAG’s default preference.

But a single ‘Moonshot Programme Office’ would be so big that it would ‘bend light’ inside ESA and require special arrangements and authorisations. The most important of these is ‘commercially-oriented procurement’ which Revolution Space correctly highlights as the key reform that would complement the geo-return rule. The idea, based on fixed-price contracts and gated payments, is openly borrowed from NASA’s successful commercial cargo and crew programmes servicing the ISS.12For the origins of this approach see:Mike Griffin, Speech: ‘NASA Administrator Mike Griffin Remarks to the Space Transportation Association’, NASA, 21/06/2005, https://bit.ly/3OXIFbi (checked: 05/06/2023).

The Moonshot endeavour may not evolve quite to the point of having more of a ‘programme with an agency attached’ rather than ‘an agency with a programme’, but perhaps not far from it. How to handle this scale and complexity, and still deliver effectively – particularly since ESA’s own fate will come to be increasingly seen as closely tied to the fate of the Moonshot programme?

The dilemma may be summarised by asking to choose two of these three elements of success:

- Speed (of delivery);

- Cost-effectiveness; and,

- Safety (programmatic safety in terms of political risk, rather than technical failure).

ESA may opt for a light-touch, commercially-oriented programme management model with wide authorities and autonomy, borrowing some principles from US Space Force’s Space Rapid Capabilities Office (RCO),13The US Space Force’s Space RCO, an acquisitions organisation, stands out through special arrangements and contracting authorities that allows it to operate very quickly – shortcutting many of the usual approvals processes. for example. In this way it could move faster and cheaper – but it would leave it vulnerable politically when any difficulties arise.

An Apollo-style model, big, highly integrated and with the full power of countries behind it, could also move quickly if it had strong political backing – but it would be very expensive. Finally, a standard model, similar in approach to what we have today but perhaps with some improvements at the margins, could keep costs under control and politicians on its side – but it would inevitably move slowly and cautiously.

A fast, cheap and politically-safe way to run a big space programme that is benchmarked to Apollo does not exist. European decision-makers will have to decide what matters most to the overall success of the initiative, and what trade-offs can be best accommodated. Importantly, the project management approach chosen should be in line with, not contradict, the core purposes of the programme. Revolution Space identifies speed of execution, for example, as a key reason to put this programme in motion in the first place: Europe does not want to lose touch with the frontrunners in the ‘space race’.

5.2 Programme governance: Politics

No single aspect of a European Moonshot programme is more important – and more tricky – than its politics.

The first dilemma is: who would be in charge and who would actually own the resulting capabilities? The two questions are interrelated. Apollo was straightforward: directed and owned by NASA for the US Government, with Congressional oversight. The model is essentially the same for the main elements of Artemis today, but with a stronger international and commercial involvement.

Europe’s current format for handling major programmes like Galileo or Copernicus is that the EU funds and owns the operational capability, with ESA responsible for research and development and overall programme management including verification and launch, with manufacturing outsourced to industry.

This governance/ownership model does not seem to suit a European Moonshot programme and it would likely be fatal to the project if it were attempted. This is mainly because EU institutional ownership would inevitably turn the resulting capability into a closed system, in which countries such as the UK could not participate on acceptable terms. Under EU control, it is designed to do so, in the name of ‘autonomy’ and ‘security’. The bureaucratic and political complexities – mirroring the very nature of the EU – would slow down the programme as has happened in every case before, and would only multiply in time. The mandatory alignment with the EU’s protectionist rulebook would likewise run against the original ethos of Revolution Space.

On the other hand, from a political standpoint a European Moonshot programme worthy of that designation simply cannot happen without EU involvement: the scale and strategic importance of the enterprise would be too big for it to somehow exist completely outside the EU system. Besides, only the EU has the means and instruments to marshal the kind of financial resources needed to bring the programme into existence – if not necessarily to see it through. However, this need not require EU ownership: creative solutions could be found for an intermediary model. This could be a new non- or inter-governmental organisation (for example, a ‘European Cis-Lunar Organisation’, or ECLO) like the original Intelsat and Inmarsat, or ISS, to manage the assets and share the benefits. This new institution might also be used more broadly as the coordinating body between the EU and ESA on this particular programme.

As far as ESA is concerned, the agency should tread with great caution. The institutional tension between ESA and the EU, has been skilfully handled so far by the Director General.14Gabriel Elefteriu, ‘Copernican Revolution’, Policy Exchange, 31/08/2022, https://bit.ly/43yGqz8 (checked: 05/06/2023). The agreement he negotiated in 2021 provides a stable framework for ESA-EU collaboration.15The agreement was the Financial Framework Partnership Agreement, see: ‘N° 20–2021: ESA and EU celebrate a fresh start for space in Europe’, European Space Agency, 22/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3NakCV8 (checked: 05/06/2023). But the balance is fragile, and EU politics are constantly changing. If ESA is able to obtain a strong mandate – funding and new commercial authorities – to run a Moonshot programme in a way that is less tied to the EU, that would cement its independence and open a new world of possibilities for European space in general.

On the other hand, the bigger the task, the bigger the risks. ESA would take the blame for any complications, failures or delays – a boon to the advocates of an EU takeover of the agency. There are a number of potential political traps here, perhaps the most evident being that ESA may be allowed to get beyond a point of no (political) return with the Moonshot plan in the expectation of a strong mandate, only to be forced later in the political process to take on all the responsibility but without the authorities and freedom it needs. Finally, a massive new programme could also suck the oxygen out of other ESA activities and end up disrupting the organisation in various ways, particularly given its multinational structure.

6.0 Is Moonshot financeable?

Requiring a roughly 25-30% hike in ESA’s budget, a European Moonshot programme will be very difficult to finance in full from the usual institutional coffers, whether EU or national governments. This is why Revolution Space correctly emphasises the need to tap into private sources of investment through more commercial approaches in the form of ‘public-private partnerships’. But significant moves in that direction will have to be either reconciled with the rule of georeturn,16According to which a member state’s annual investment in the ESA should return to its domestic space industry in the form of ESA contracts. or bypass it through some new tailored arrangements.

6.1 Competitiveness

Private investors – many of them being funds with an investment horizon of six to seven years – will look closely at projected revenues, especially over the short-medium term. However, when it comes to the most accessible space economic opportunities, such as LEO crew and cargo transport, LEO stations and in-space assembly and manufacturing, Europe is late to the party: even today in 2023 the market is arguably over-supplied. By the time the European Moonshot programme rolls out its own versions of what the commercial sector offers now, the competition will likely have locked in an unassailable advantage in strictly commercial terms.

This leads to a hint of contradiction implicit in Revolution Space. The bullish tone on the economic potential of space in general is paired with an implicit acknowledgement that the ‘public sector’ will have to carry much of the weight as ‘anchor customer’ and commit to a long-term programme – irrespective of market realities. Of course, the US itself used this approach to foster its powerful NewSpace sector including SpaceX. A key reason why it worked – aside from the scale of the funding available – was that the Americans were first to market: there was no competition to worry about, from an investment perspective. Trying to emulate this dynamic in Europe, with significantly lower resources and against formidable existing competition, makes for a very different economic proposition for prospective investors.

This is not a counsel of despair with regards to the chances of attracting private capital – but it is an encouragement to be very realistic about the situation and not simply assume that investors will see the same financial merits in this programme as the HLAG does, or that they will easily ‘get out of their comfort zone’ as Revolution Space suggests. More creative financing arrangements might have to be considered in order to attract private money.

6.2 Other financing mechanisms

By leveraging bodies like the European Central Bank (ECB), European Investment Bank or the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the EU and wider Europe’s institutional power could assist in accessing investment capital through new financing mechanisms or bodies.

One of these can be a ‘European Space Investment Corporation’ (ESIC) that could offer AAA-rated loan guarantees backed by the ECB to space companies, as well as credit support to private space venture capital funds which reduce the latter’s risk. Space bonds to fund certain components of the Moonshot programme might also be envisaged, perhaps with EBRD involvement. Companies holding an ESIC-issued loan guarantee would be able to borrow money from commercial banks at lower cost in order to fund their growth. Depending on how it is set up, ESIC could function as an EU or an intergovernmental organisation (including with non-EU members), with a mission to promote private space investment and commercialisation across the European region in a stable, sustainable manner.

Another – complementary – solution could be a venture capital arm established either within ESA or under ESA’s direction, for strategic direct equity funding of smaller European space technology companies. It could be capitalised by a combination of EU institutions, willing ESA member states, ESIC (if formed) and perhaps private finance as well. This venture capital fund would benefit from ESA’s general expertise and technical due diligence capabilities, and would offer a unique route into the European space programme for new companies (including international ones). The closest parallel is the Central Intelligence Agency’s In-Q-Tel which has been demonstrably effective in raising finance for firms in advanced stages of developing key technologies with intelligence applications. This venture capital model would differ from ESA’s Open Sky Technologies Fund which is externally managed and focused on seed capital.17‘Open Sky Technologies Fund’, European Space Agency, No date, https://bit.ly/3Neszc3 (checked: 05/06/2023).

7.0 The way forward

In any realistic scenario a European Moonshot programme will involve trade-offs, and therefore risk. The key is to trade those aspects where risk can be mitigated most effectively, often through the application of other European instruments of statecraft. The more deeply space is integrated with Europe’s other strategies – rather than being compartmentalised as a separate project – the more can be done. This is the power of policy integration: making Europe – the totality of the EU and ESA system – work for space, not just space work for Europe.

Trade-offs include:

- Expanding Europe’s industrial and technological capacity to deliver a Moonshot programme relatively quickly will be a trade-off between costs, external (non-European) involvement, and programme size.

- Programme management choices involve a trade-off between effectiveness, the level of political control and programme complexity. A transformed, more effective ESA will require a freer hand but this could also make it more vulnerable politically.

- Setting up a stable governance framework will be a trade-off between EU institutional power (with its benefits and constraints) and wider non-EU European/international involvement, as well as between the EU and ESA itself.

- Unlocking private finance is firstly a trade-off between programme architecture decisions (with their associated market prospects) and EU institutional support (including through regulation).

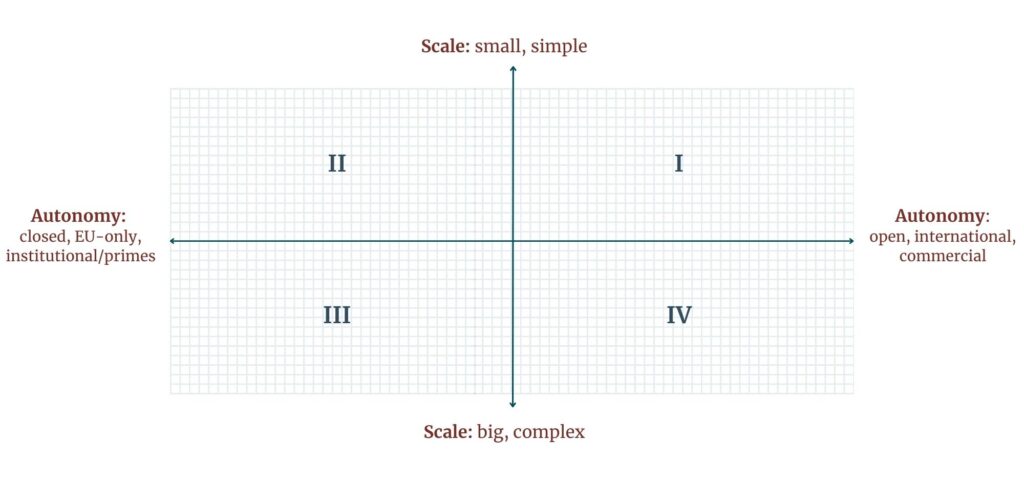

These considerations do not necessarily map out neatly across all the aspects of such a far-reaching vision as that outlined in Revolution Space. But two overarching trade-off themes emerge: autonomy (as a function of the programme’s openness and commercially-minded approach) and scale (as a function of the programme’s complexity both in terms of scope and of governance and authorities). These two fundamental dimensions can provide the axes for a visual summary of Europe’s Moonshot dilemma:

In addition, four key variables or programme characteristics can be distilled from the preceding discussion on tests, solutions and trade-offs:

- Politics. This estimates the relative difficulty of obtaining political backing for the proposed version of the programme. In practice, there are multiple subsidiary elements that enter the political calculation.

- Cost. This refers particularly to the direct institutional funding required (cost to the taxpayer) rather than the total programme cost (which may be shared with the private sector).

- Risk. This refers to the risk that the programme may ‘fail’, either by losing political support or by experiencing delays, cost overruns and other implementation problems. It is a measure of programme stability, effectiveness and sustainability.

- Goals. This provides an aggregate measure of the degree to which that particular version of the programme meets the goals and vision of Revolution Space.

These variables are necessarily subjective, notional and generalist, gross approximations, but can be applied to each quadrant of the graph in order to further clarify programme options:

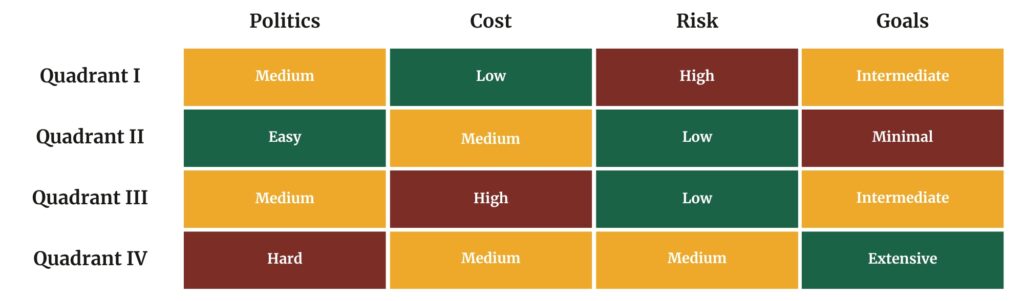

Quadrant I suggests a smaller, nimbler core ‘in-house’ programme coupled with a highly commercial approach (open to non-EU partner nations and businesses) and wide authorities for the implementing entity (presumably ESA). This is the opposite of Europe’s instincts and traditional practices: a new way of doing things, which accounts for the high risk factor. On the other hand, heavier reliance on market solutions means this is the cheapest way to take Revolution Space forward. The low cost also mitigates some of the political resistance always associated with major reform and, in this programme version, also with the implied compromise on European autonomy (which accounts for the lower score on Goals). Such a market-friendly, competition-focused approach also creates new coalitions of political support among those in Europe who think the old models no longer work.

Quadrant II likewise suggests a pared-down programme, perhaps choosing to focus on just one element of the Revolution Space architecture – for example, crew and cargo to LEO. Together with a strong adherence to the principle of ‘autonomy’, this would ensure the least political difficulties of all these programme versions. Costs are higher than in Quadrant I because of less optimal (or even very restricted) international and commercial involvement, in the name of ‘autonomy’. Even if it does include an element of procurement and management transformation – moving a bit outside of the ‘comfort zone’ – this package essentially carries a low risk given its compatibility with the European system. It also misses the mark, however: it offers something to all stakeholders but the results are average and fail to achieve the strategic impact aimed for by HLAG.

Quadrant III illustrates the classic ‘dirigiste’ approach to large programmes (e.g. Ariane) that is tailor-made for the big industrial players. This is what is normally expected from a protectionist, highly bureaucratic Europe that often discourages real competition in favour of ‘national champions’. The consortium recently formed to bid for the IRIS project is a case in point.18Keith Cowing, ‘European Space and Telecoms Players Sign Partnership Agreement to Bid for IRIS2 Constellation’, 03/05/2023, SpaceRef, https://bit.ly/3WNSD0C (checked: 05/06/2023). Quadrant III is the most expensive programme option, and for that very reason, it is paradoxically easier to back by European politicians than what the sheer cost might suggest. Being ‘business as usual’, the risk of total failure is low while the scale of funding will inevitably produce some notable results, as any well-resourced industrial policy does. Thus it meets some of the key goals of Revolution Space – boosting industry and developing new autonomous capabilities – hence the medium ranking. But it does not fundamentally alter Europe’s relative space standing compared to the US or PRC.

Quadrant IV suggests a version of the programme that is the comparative best of all worlds in terms of price, outcomes and chances of success – but is a very difficult political ‘sell’. It retains the scope and technological ambition proposed by Revolution Space and requires major public funding, but also draws fully on what the global private space sector has to offer. Autonomy is traded for commercial participation which, together with the investment available, quickly expands Europe’s space sector and global market share. This meets all the key goals, with European space autonomy arising in time as a commercial rather than an institutional proposition. The significant medium risk is very much tied to the new European institutions and mechanisms – particularly financial – that will have to be set up to handle the unique mix of financing needed at scale for this option.

7.2 The optimal programme?

For the UK, the most acceptable proposition would be a very light ‘technology portfolio’ approach (which would be a Quadrant I option), where the British industry and research community can offer strong research capabilities and even unique technologies. These may include, for example: nuclear propulsion, space-based solar power or the single-stage-to-orbit SABRE engine by Reaction Engines (which could give Europe a unique advantage). However, it is unlikely that this particular pathway will find much support in Europe as long as the ‘Moonshot’ concept drives the discussion.

It is in Quadrant IV, therefore, where UK and European interests can find a point of convergence. The parameters of Quadrant IV appear to provide the optimal high-level programme template for what Revolution Space seeks to achieve, and what is achievable politically. We can cross-reference it with the tests and solutions discussed in the preceding sections to identify some of the policy and programmatic requirements. These include:

- Scope: The programme architecture would retain the full Earth-to-Moon ambition of Revolution Space, but there would be a mixed or hybrid approach to developing its component capabilities. ESA could focus on certain aspects of LEO and lunar infrastructure and technologies, using both traditional and new types of contracting to advance projects in parallel not sequentially. Capability gaps will be covered through contracts – or even licensing or leasing – with commercial providers where mature solutions already exist.

- Access: The programme would be open to non-EU, non-European partners, whether national agencies or space companies, with requirements for jobs creation and/or technology transfer where necessary. International legal agreements would be negotiated to lock-in European access to certain foreign commercial capabilities – e.g., LEO transportation – and reduce associated political risks. This includes negotiating ways around the US export control rules including potentially the International Traffic in Arms Regulations. Britain and most recently Australia have demonstrated this is possible, with their custom Technology Safeguards Agreements (TSA) signed with the US.19 For the UK-US TSA, signed in June 2020, see: ‘UK-US Technology Safeguards Agreement (TSA) for Spaceflight Activities: Understanding the TSA’, Foreign, Common and Development Office (UK), 08/02/2021, https://bit.ly/42jj0fX (checked: 05/06/2023). For the Australia-US TSA, see: ‘Australia and US reach in-principle agreement on technology safeguards agreement’, Department of Industry, Science and Resources (AU), 24/05/2023, https://bit.ly/42kJ5LH (checked: 05/06/2023). This ‘open system’ approach would create programme stakeholders well beyond Europe, with geopolitical and economic benefits.

- Governance: A Programme Management Office running the European Moonshot would be created within ESA with a separate budget and radical new procurement and service contracting authorities – similar to US’ Space RCO and the Space Development Agency – circumscribed specifically to this programme. Key programme assets would be owned by a new intergovernmental organisation with mixed participation (both the European Commission and national governments), similar to the ISS – and/or the original Intelsat.

- Financing: There would be a number of different financial mechanisms and sources involved, including a new European Space Investment Corporation. Only a minority of the total investment value would come directly from the EU or national budgets. The majority of the funding gap would be covered – depending on the programme element in question – by private investors, bond issues, and by lowering costs through increased competition in the European space sector.

8.0 Conclusion

The Revolution Space report has opened the most remarkable opportunity in a generation for turbocharging Europe’s space enterprise. As the debate rolls on to the European Space Summit in November 2023, the hard facts might sink in and lead to a pragmatic plan of action.

One of the most striking things about Revolution Space is just how British some of its key arguments are, particularly around the need for a more commercial mindset and reform of ESA’s procurement approaches, with an emphasis on fostering innovation, competitiveness and attracting more private investment. Almost uniquely among European countries, this has been the UK’s space policy model for decades and can now emerge as a point of compatibility rather than divergence with other European nations.

Neither the hope of a genuinely new ‘commercial turn’ in Europe, nor the fear of a big programme nearby which it might be locked out of, are in themselves enough to move the UK towards a meaningful engagement with Revolution Space right now. What will make the difference is whether it looks like the Moonshot programme might take a form that makes sense from a British perspective.

This report identifies an ‘optimal’ version of a programme that could be the basis for discussions, but hard choices will be required. A number of headline problems – to do with programme management, or financing, for example – have also been identified here, together with some illustrative solutions. A few other important topics were left out, such as defence and security, regulation, or the ‘inspiration’ dimension.

There should be no doubt as to the scale of the political challenge in reaching consensus on a credible programme. It requires, for example, the creation of new institutions and a compromise on the defensive idea of ‘European space autonomy’ in favour of a potentially smarter, more front-footed version based on commercial prowess. Most of all, it requires a lot of money. The question, however, is not whether Europe should make this investment; rather, it is: can it afford not to?

About the authors

Gabriel Elefteriu FRAeS is Deputy Director at the Council on Geostrategy, where his research focuses on defence and space policy. Previously he was Director of Research and Strategy and member of the Senior Management Team at Policy Exchange, which he first joined in 2014 and where he also founded and directed the first dedicated Space Policy Research Unit in the United Kingdom. Gabriel is also an Associate of King’s College, London, an elected Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society, and a founding partner at AstroAnalytica, a space consultancy. He holds a BA in War Studies (first class) and an MA in Intelligence and International Security (Distinction), both from King’s College, London.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his special thanks to Professor David Southwood CBE for his counsel and support. All opinions and recommendations expressed in the text, along with any remaining errors and inaccuracies, are the author’s own.

Disclaimer

This publication should not be considered in any way to constitute advice. It is for knowledge and educational purposes only. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Council on Geostrategy or the views of its Advisory Council.

Embedded image credit: ESA/J.Mai, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

No. GPPP04 | ISBN: 978-1-914441-41-7

- 1Britain remains part of ESA which is not an EU agency.

- 2‘Revolution Space’, European Space Agency, 23/03/2023, https://bit.ly/3qq1Eko (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 3Allegedly, a mission to Mars was briefly considered for inclusion in the report, but ultimately deemed as not credible.

- 4‘Eurospace Facts and Figures 2021’, ASD Eurospace, 16/07/2022, https://bit.ly/45GKr6B (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 5Ibid.

- 6‘Eurospace Facts and Figures 2020’, ASD Eurospace, 16/07/2021, https://bit.ly/43LTm4V (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 7‘Eurospace Facts and Figures 2021’, ASD Eurospace, 16/07/2022, https://bit.ly/45GKr6B (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 8‘Eurospace Facts and Figures 2020’, ASD Eurospace, 16/07/2021, https://bit.ly/43LTm4V (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 9‘The Cost of SLS and Orion’, The Planetary Society, No date, https://bit.ly/3ISbCkL (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 10‘NASA Awards Lockheed Martin Contract For Six Orion Spacecraft’, Lockheed Martin, 23/09/2019, https://bit.ly/43mhSd3 (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 11‘Orion Reference Guide’, NASA, 10/11/2022, https://bit.ly/3NmSTAR (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 12For the origins of this approach see:Mike Griffin, Speech: ‘NASA Administrator Mike Griffin Remarks to the Space Transportation Association’, NASA, 21/06/2005, https://bit.ly/3OXIFbi (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 13The US Space Force’s Space RCO, an acquisitions organisation, stands out through special arrangements and contracting authorities that allows it to operate very quickly – shortcutting many of the usual approvals processes.

- 14Gabriel Elefteriu, ‘Copernican Revolution’, Policy Exchange, 31/08/2022, https://bit.ly/43yGqz8 (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 15The agreement was the Financial Framework Partnership Agreement, see: ‘N° 20–2021: ESA and EU celebrate a fresh start for space in Europe’, European Space Agency, 22/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3NakCV8 (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 16According to which a member state’s annual investment in the ESA should return to its domestic space industry in the form of ESA contracts.

- 17‘Open Sky Technologies Fund’, European Space Agency, No date, https://bit.ly/3Neszc3 (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 18Keith Cowing, ‘European Space and Telecoms Players Sign Partnership Agreement to Bid for IRIS2 Constellation’, 03/05/2023, SpaceRef, https://bit.ly/3WNSD0C (checked: 05/06/2023).

- 19For the UK-US TSA, signed in June 2020, see: ‘UK-US Technology Safeguards Agreement (TSA) for Spaceflight Activities: Understanding the TSA’, Foreign, Common and Development Office (UK), 08/02/2021, https://bit.ly/42jj0fX (checked: 05/06/2023). For the Australia-US TSA, see: ‘Australia and US reach in-principle agreement on technology safeguards agreement’, Department of Industry, Science and Resources (AU), 24/05/2023, https://bit.ly/42kJ5LH (checked: 05/06/2023).