For many decades, if not centuries, the United Kingdom (UK) has been attractive, innovative and powerful. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the agricultural and industrial revolutions, combined with Britain’s freer and more open political system, gave the country an edge over its competitors. Foreign governments have envied the UK’s success and influence and have often sought to weaken it by reframing it in accordance with their own interests on the international stage. Authoritarian regimes such as Russia’s kleptocracy and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) – defined as ‘systemic competitors’ by Her Majesty’s (HM) Government1‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 16/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 14/06/2021). – have been particularly determined to degrade Britain and encourage others to believe that it is a declining and increasingly inconsequential power. For altogether different reasons, even the UK’s allies – particularly the United States (US), Germany and Japan – have tried to position it on the international stage.

With this in mind, the Council on Geostrategy commissioned a series of research papers during Spring 2021 to identify the nature of ‘discursive statecraft’ – particularly in the form of national ‘positioning operations’ – to ascertain how the UK is being positioned as a power. The first paper in the series introduced ‘discursive statecraft’ as a concept – see Box 1 – as well as national ‘positioning’ operations.2James Rogers, ‘Discursive statecraft: Preparing for national positioning operations’, Council on Geostrategy, 08/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3moT0N7 (found: 14/06/2021). These account for a specific form of discursive statecraft whereby foreign governments attempt to impose a target country with a new identity and international position. At the same time, the Primer situated discursive statecraft in relation to the Integrated Operating Concept 2025 – the Ministry of Defence’s revolutionary doctrinal contribution to the Integrated Review – and made an essential distinction between the discursive statecraft of friend and foe: opponents tend to engage in discursive statecraft ‘to destabilise their target, force it onto the backfoot, and stir up domestic political tensions’, while allies use it to have ‘political impact’ in their target, namely to secure their own interests.3Ibid. For the Integrated Operating Concept 2025, see: Integrated Operating Concept 2025, Ministry of Defence, 30/09/2020, http://bit.ly/ioc2025 (found: 14/06/2021).

Box 1: Discursive statecraft in a nutshell

Discursive statecraft results when countries seek to articulate concepts, ideas, and objects into new discourses to degrade existing political and ideological frameworks or generate entirely new ones. It could be likened to a ‘proactive’ or ‘offensive’ form of soft power. In the final instance, such efforts are designed to (re-)structure how people can think and act, as well as what can be said and thought. This can involve the projection of vast new ideological or geostrategic formations, such as ‘democratic liberalism’, ‘Soviet communism’, ‘the West’, the ‘non-aligned’, and ‘the Third World’, during the Cold War. But it can also involve positioning operations to alter and restructure another country’s understanding of its place in the world and encourage its leaders (and other nations) to accept new narratives about the target.

As Box 2 shows, the first Primer was followed by three empirical studies. The first two focused on how the Kremlin and the CCP position the UK, and the third analysed how Britain is positioned by the US, Germany, and Japan.4See: Andrew Foxall, ‘How Russia positions the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/35AzaH8 (found: 14/06/2021); Matthew Henderson, ‘How the Chinese Communist Party ‘positions’ the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 22/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3nizzWq (found: 14/06/2021); and Philip Shetler-Jones, ‘How allies ‘position’ the United Kingdom, Council on Geostrategy, 06/05/2021, https://bit.ly/2TJpibc (found: 14/06/2021). Russia’s kleptocracy and the CCP were selected because HM Government had identified them as the UK’s most resourceful competitors.5Russia was identified as an ‘acute direct threat’ and the PRC was identified as a ‘systemic competitor’ in the Integrated Review. See: ‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 16/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 14/06/2021). The US was chosen because it is Britain’s most powerful ally; Germany was selected as the most influential country in continental Europe, the UK’s neighbourhood, while Japan was chosen as Britain’s leading ‘quasi-ally’ in the Indo-Pacific – identified in the Integrated Review as a region of growing strategic significance.6See: Philip Shetler-Jones, ‘How allies ‘position’ the United Kingdom, Council on Geostrategy, 06/05/2021, https://bit.ly/2TJpibc (found: 14/06/2021).

Box 2: Papers in the national positioning series

1. Discursive statecraft: Towards national positioning operations

2. How Russia ‘positions’ the United Kingdom

3. How the Chinese Communist Party ‘positions’ the United Kingdom

4. How allies and partners ‘position’ the United Kingdom

5. Discursive statecraft: Resisting national positioning operations

This Primer is the final paper of the series on discursive statecraft and national positioning. It begins by summarising how Russia’s kleptocracy, the CCP, and the governments of the US, Germany and Japan, respectively, position the UK on the international stage. Through a matrix, it then provides options for how HM Government could respond to discursive statecraft, particularly when Britain comes under attack from hostile authoritarian powers. Finally, it looks at how HM Government has already responded to the challenge of discursive statecraft before proposing a more proactive approach that intersects with the Integrated Review’s commitment to uphold collective security in a more competitive age.

How is Britain being positioned?

As the Council on Geostrategy’s three empirical studies have shown, foreign powers – both friend and foe – have sought to position the country as a specific kind of international actor. This positioning tends to take two forms depending on whether or not the protagonist sees the UK as an ally or opponent. Opponents attempt to degrade the UK and undermine its authority and global standing, often using aggressive or demeaning language:

- Although the Kremlin does not see Britain to be its equal in terms of size and power – only the US and People’s Republic of China (PRC) are seen as Russia’s peers – it sees the UK as a dangerous foe. For this reason Russia’s kleptocracy actively positions the UK as a ‘small island’ that the rest of the world should simply ignore;7Andrew Foxall, ‘How Russia positions the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/35AzaH8 (found: 14/06/2021).

- Confident of its own growing power, the CCP – the regime in control of the PRC – positions the UK equally dismissively. The CCP’s mouthpieces tend to frame the British economy as moribund and in need of Chinese investment. Britain is itself positioned as a spent force in international relations searching for past glories. In addition, CCP narratives emphasise the UK’s status as a former colonial power, whose impact has been generally negative.8Matthew Henderson, ‘How the Chinese Communist Party ‘positions’ the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 22/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3nizzWq (found: 14/06/2021).

The UK has also been positioned by its leading allies. Of the three allies studied – Germany, Japan and the United States (US) – each positions Britain differently. Unlike competitors, allies generally do not seek to harm one another but instead try to instrumentalise a target ally’s power, restrain its policies per their own interests, or reinforce their own identities:

- Using the prism of the ‘special relationship’, the US positions the UK to instrumentalise British power and direct and restrain HM Government’s sense of its own policy choices. American positioning of Britain also appears to serve another objective: to reinforce the US’ identity as a responsible international actor;

- Germany positions the UK to instrumentalise its more militarily powerful Euro-Atlantic ally and encourage it to support European security in accordance with German preferences, restrain the UK as an economic ‘rival’, and reinforce the German vision of the European Union (EU) (and, by extension, Germany’s own identity as a responsible European actor);

- Japan positions the UK to instrumentalise British power to draw it into helping to uphold the Japanese vision of a ‘free and open’ Indo-Pacific, restrain HM Government from ‘disorderly’ actions that might hurt Japan’s economic interests, particularly in the EU, and reinforce aspects of Japanese national identity.9Philip Shetler-Jones, ‘How allies ‘position’ the United Kingdom, Council on Geostrategy, 06/05/2021, https://bit.ly/2TJpibc (found: 14/06/2021).

In the case of Russia’s kleptocracy and the CCP, it is clear from the language and narratives projected by their representatives and mouthpieces that both have hostile intentions towards the UK, namely to harm the country’s standing and undermine HM Government’s international reach and influence. Conversely, although allied positioning operations can have a significant impact on their targets – recall the robust British response to the intervention of Dean Acheson, then US Secretary of State, in 1962 when he asserted that the UK ‘had lost an Empire but not yet found a role’10Acheson’s exact statement was: ‘The attempt to play a separate power role – that is, a role apart from Europe, a role based on a special relationship with the US, a role based on being head of a “Commonwealth” which has no political structure, or unity, or strength – that role is about played out.’ See: Gavin Hewitt, ‘US-UK: Strains on a special relationship’, BBC News, 20/04/2016, http://bit.ly/uusoass (found: 14/06/2021). – they do not intend to degrade an ally’s power; instead, they seek to instrumentalise or restrain it, or use it to reinforce their own identities. As one of the most powerful allies of the US, Germany and Japan, respectively, it is no surprise that the UK has been subjected to positioning efforts.

Foreign positioning operations: strategic options

Doing nothing to meet the challenge of discursive statecraft is not an option in an increasingly competitive era, which is occurring increasingly in the ‘grey zone’ between peace and war. In keeping with the conclusions of the IOC2025 and the Integrated Review – indeed, even, to ‘radicalise’ them – HM Government ought to develop a thoroughly integrated and expansive response. To begin with, the UK should firm up its own political and economic institutions so that they are less accessible to foreign powers which might seek to exploit or corrupt them. Measures have already been taken – or are planned – to make it harder for hostile states to get inside Britain’s political ecosystem.11This point is expanded on thoroughly by Andrew Foxall. See: Andrew Foxall, ‘How Russia positions the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/35AzaH8 (found: 14/06/2021). HM Government should also increase its own situational awareness of rivals’ attempts to position the UK. Beyond those relatively easy and defensive measures, there are potentially four ways the UK could respond.

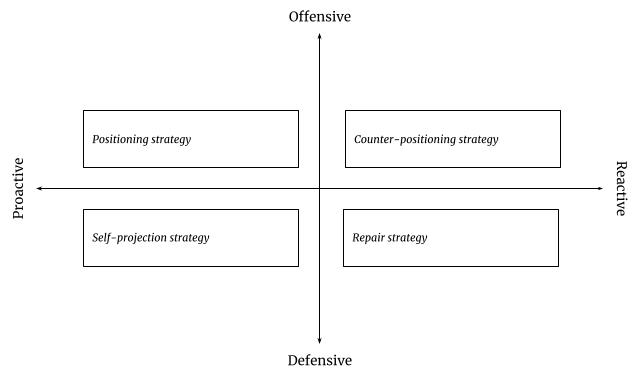

Figure 1: Options for responding to national positioning operations

As Figure 1 shows, these policy responses can be delineated through a matrix, based on two axes: the first identifies whether Britain should adopt an ‘offensive’ or ‘defensive’ approach, in other words, whether it should seek to undermine opponents actively or whether it should simply project positive narratives about itself. The second axis determines whether the UK approach should be proactive or reactive. This results in four possible directions:

- Positioning strategy: Go proactively on the offensive and adopt positioning strategies for target countries. For example, exploit the vulnerabilities of authoritarian opponents, emphasise their weaknesses, and humour and undermine their leaders using sophisticated discursive and social media campaigns.

- Counter-positioning strategy: Respond with a counter-positioning offensive if a foreign power unleashes its own offensive positioning operations against the UK. For example, if a foreign government attempts to degrade Britain on the international stage, attack and subvert the opponent’s own narratives and strike out at its global position and role. The form of the response may be similar to a positioning strategy, but it would also need to correct and push back against the protagonist’s own attempts to position the UK.

- Self-projection strategy: Simply project positive narratives about the UK in an attempt to shore up the country’s international reputation, standing and authority. Cultivate British ‘soft power’ – constitutional monarchy, democracy, technology and scientific achievement – and promote the country’s global and Euro-Atlantic security contributions to help uphold an open international order.

- Repair strategy: React to foreign positioning attacks by attempting to swiftly repair any damage inflicted by a foreign government to what Britain stands for. This may involve challenging the initial attack in such a way as to re-articulate the UK’s international position, but it would not include attempts to counter-position the protagonist.

None of these approaches is a priori the right one; the approach selected should depend on whether there is a hostile protagonist and how it attempts to position the UK on the international stage.

How should Britain respond?

In recent years, HM Government has already adopted a number of approaches not so dissimilar to those outlined above. Prime Minister David Cameron’s response to Vladimir Putin’s official spokesperson’s alleged dismissal in 2013 of the UK as a ‘small island’ that ‘nobody listens to’ represents a clear repair strategy. Cameron swiftly reacted to the Kremlin’s slight by issuing a strong rebuttal of the allegations, as he simultaneously emphasised the positive contributions his country had made to science, economics, politics and art.12See: Patrick Wintour, ‘David Cameron: UK may be a small island but it has the biggest heart’, The Guardian, 06/09/2013, http://bit.ly/dcumbasibihtbh (found: 14/06/2021).

Meanwhile, HM Government’s explanation of ‘Global Britain’ in 2018 comes close to a self-projection strategy,13See: ‘Global Britain: delivering on our international ambition’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 13/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3q8VnWg (found: 14/06/2021). as does Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s statement issued on the eve of the G7 Summit in Cornwall:

Britain has the biggest defence budget in Europe, making us central to this effort. We are contributing more troops than any other country to NATO’s deployment in Poland and the Baltic states. We have committed our nuclear deterrent and our cyber-capabilities to the alliance. Britain is doing more to guarantee the security of our continent than any other European power.

Wherever you look…Britain is the “buckle that fastens, the hyphen that joins” everything together, to adopt Walter Bagehot’s phrase. We can do this because of the breadth of our capabilities and friendships.14Boris Johnson, ‘G7 Summit is a chance to show the world our values’, 10 Downing Street, 10/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3cQkqYB (found: 14/06/2021).

On occasion, HM Government has also adopted a more offensive approach, even if only when provoked. Theresa May, then Prime Minister, attempted to counter-position the Kremlin in 2017 when she publicly admonished it during her speech to the Lord Mayor’s Banquet. Responding to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and suspected interference in the democratic processes of many free and open countries – including the UK – the prime minister described the Russian kleptocracy as the ‘chief…threat’ to the ‘international order on which we all depend’. She ended with an unambiguous statement:

I have a very simple message for Russia. We know what you are doing. And you will not succeed. Because you underestimate the resilience of our democracies, the enduring attraction of free and open societies, and the commitment of Western nations to the alliances that bind us.15Theresa May, Speech: ‘PM speech to the Lord Mayor’s Banquet 2017’, 10 Downing Street, 13/11/2017, https://bit.ly/39uZRPR (found: 14/06/2021).

Unfortunately, her rebuke was followed only a few months later by a Russian attempt at ‘wetwork’ – with nerve agents – on the streets of Salisbury. While there may not be a linkage between the two, May’s warning clearly failed to deter the Kremlin from thinking that the UK was a soft target. It remains to be seen if the more effective British counter-positioning pushback to the attempted murder of Sergei and Julia Skripal deters the Kremlin from future attacks.

To be sure, a defensive and/or reactive approach has its place: the UK needs to continue to close off its political, economic and cultural institutions from foreign interference, just as it ought to improve at discursive self-projection and repairing any damage inflicted by opponents. In the more competitive geopolitical environment of tomorrow, Britain needs to project confidence and authority, as well as a clearer vision – see Annex 1 – of what it stands for in the middling years of the twenty-first century. Critically, this ought to include discursive pushback against those domestic separatist forces whose objectives are to pull the UK apart.16Nigel Biggar and Doug Stokes, ‘How “progressive” anti-imperialism threatens the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 10/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3gKLGsM (found: 14/06/2021). It should also involve reversing the budget cuts to the British Council and BBC World Service; those cuts have only served to undermine Britain’s ability to project a positive image of itself internationally – and just as authoritarian rivals, such as the PRC and Russia, have poured new resources into their Confucius Institutes, Russkiy Mir Foundations and propaganda mouthpieces.17According to the British Council, the number of Confucius Institutes expanded from 320 to 507 between 2013 and 2018, while the number of Russkiy Mir Foundations increased from 82 to 171 over the same period. See: John Dubber (ed.), ‘Soft power superpowers: Global trends in cultural engagement and influence’, British Council, 2018, https://bit.ly/35EInOy (found: 14/06/2021).

Yet, HM Government can ill-afford to be only defensive and reactive when dealing with opponents. The UK needs to be more prepared to ‘put a bit of stick about’ – to cite the amusing quip by Francis Urquhart, Chief Whip in the political satire House of Cards.18Episode 1, House of Cards, BBC 1, 19/11/1990. In other words, Britain ought to go on the discursive offensive to strategically reposition its authoritarian opponents. Here, the Integrated Review and the IOC2025 that came before it have ambition in terms of pushing back against Britain’s rivals.

The question is: what should a more proactive and offensive strategy look like? First, HM Government would need to attempt to ‘deactivate’ or ‘scramble’ the existing identities of hostile powers. This might involve the de-synchronisation of a target’s historical narrative; publicly questioning a target’s international relevance; and delegitimising a target’s international status and role. Simultaneously, the UK would need to project and construct – working in tandem with disgruntled or separatist domestic political forces (if possible) – a new identity for the target, connecting it to new or pre-existing (but often marginalised) historical myths, before attempting to encourage the adoption and spread of the new position, both domestically (inside the target country), and internationally, among the elites of other countries. The objective of such a strategy would be to put opponents on the back foot, forcing them to spend political time and capital shoring up their own identities, leaving the UK freer to pursue its own interests.

In this sense, the maiden deployment of the Royal Navy’s Carrier Strike Group (CSG), spearheaded by HMS Queen Elizabeth, has the potential to mark the beginning of a more integrated, proactive and offensive approach – particularly if it is underpinned by effective narrative projection. By steaming through seas where revisionist powers have illegitimately indicated ‘special rights’ to international waters – whether in the Black Sea, the South China Sea, or elsewhere – the presence of the CSG (or specific vessels from the group) undermines their authority, reconfirms openness (in the form of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea), and resserts UK geostrategic reach and authority.

For example, the deployment of a British destroyer and a Dutch frigate from the CSG to the Black Sea in June 2021 openly challenges the Kremlin’s regional authority and actively delegitimises its narratives that the Black Sea is an area of privileged Russian interest. At the same time, it gives succor to British allies such as Romania and Bulgaria, and perhaps even more importantly, to the Euro-Atlantic ‘frontier’ states – Ukraine and Georgia. Simultaneously, the deployment actively demonstrates British geostrategic reach and determination to underwrite the defence of Europe, just as it reminds Russia’s kleptocracy – and those who listen to it – that the UK is not a ‘small island’ that ‘nobody listens to’, but a powerful state with the means to ignore the Kremlin’s fiat.19For an excellent analysis of the deployment of HMS Defender (and HNLMS Evertsen) to the Black Sea, see: Mark Galeotti, ‘HMS Defender in the Black Sea: What to expect’, Britain’s World, 14/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3vJp2GG (found: 14/06/2021). With clever signalling and narrative projection,20For a good example of clear and unambiguous British narrative projection, see: ‘CSG21 in the Black Sea’ (Tweet), @smrmoorhouse, 14/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3vJwPUH (found: 14/06/2021). the CSG’s further deployment into the Indo-Pacific, not least the South China Sea, should actively reinforce Britain’s status not only as – in the words of the Integrated Review – ‘one of the world’s most influential countries’, but also a country dedicated to upholding collective security.21‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 16/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 14/06/2021).

HM Government should not stop with the CSG. It should begin proactively positioning Russia’s kleptocracy and the CCP. This does not mean that Britain should adopt the Kremlin’s clumsy techniques or develop its own ‘wolf warrior’ diplomats; as the CCP has discovered, an angry tone and aggressive approach often antagonise more than they achieve.22‘Xi Seeks “Lovable” Image for China in Sign of Diplomatic Rethink’, Bloomberg, 01/06/2021, https://bloom.bg/3xCzsZM (found: 14/06/2021). What it does mean is that the UK needs to craft integrated and comprehensive strategies for discursive statecraft – underpinned by a plethora of discursive techniques – to push back against competitors. It also means that British ministers and officials – at all levels – should be freer to discursively ‘strike’ competitors or swiftly challenge them when they project hostile positions which might undermine the UK’s international standing or influence.

Conclusion

As geopolitical competition intensifies, it will become increasingly discursive. The result will be a multi-faceted struggle between the world’s leading powers for the dominance of particular political and economic narratives. These narratives – discourses – shape how others think and act and even structure what can be said and imagined. Discursive statecraft and the ability to fix meaning is at the heart of the competition for power.

As one of the world’s leading democracies and a free and open nation, the UK cannot shy away from this emerging confrontation. Given its geopolitical reach, capability and strategic intent, it will be a significant target, particularly for authoritarian powers with revisionist policies. For this reason, the Council on Geostrategy has attempted to shed light on this growing phenomenon. Going forward, HM Government ought to monitor how the UK is being positioned by its rivals while also developing positioning strategies of its own.

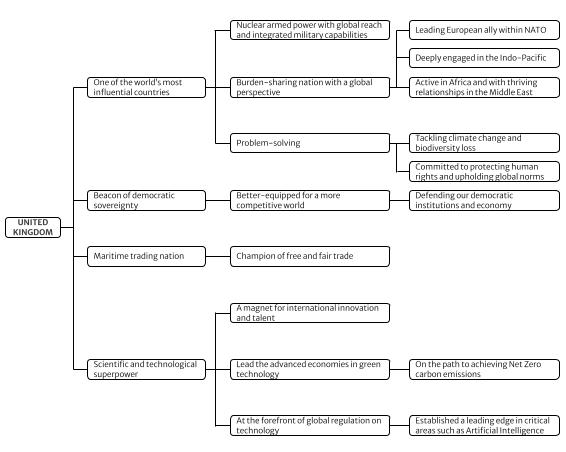

Annex 1: What the UK stands for in the 2020s

As the diagram below shows, HM Government has developed a clear vision for what the UK should stand for on the international stage. These statements, drawn directly from the ‘Prime Minister’s Vision 2030’ in the Integrated Review – and re-emphasised in different iterations throughout the rest of the document – attempt to provide an identity for Britain as a global power for the 2020s.23‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 16/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 14/06/2021). Of course, the UK is a multiparty democracy and an open society, so there are many competing visions of what the country is and what it should be, but the Prime Minister’s Vision 2030 represents the clearest articulation of HM Government’s position for Britain for the 2020s.

What the UK stands for in the 2020s:

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following for their feedback on drafts of this paper: Prof. Mark Galeotti and Prof. Luis Simon, as well as John Dobson and Richard Payne. Of course all responsibility for the contents of this paper including omissions and inaccuracies lie with the author.

About the author

James Rogers is Co-founder and Director of Research at the Council on Geostrategy, where he specialises in geopolitics and British strategic policy. Previously, he held positions at the Henry Jackson Society, the Baltic Defence College, and the European Union Institute for Security Studies. He has been invited to give oral evidence at the Foreign Affairs, Defence, and International Development committees in the Houses of Parliament. He holds an MPhil in Contemporary European Studies from the University of Cambridge and an award-winning BSc Econ (Hons) in International Politics and Strategic Studies from the University of Wales, Aberystwyth.

Disclaimer

This publication should not be considered in any way to constitute advice. It is for knowledge and educational purposes only. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Council on Geostrategy or the views of its Advisory Council.

No. SBIP01 | ISBN: 978-1-914441-09-7

- 1‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 16/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 14/06/2021).

- 2James Rogers, ‘Discursive statecraft: Preparing for national positioning operations’, Council on Geostrategy, 08/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3moT0N7 (found: 14/06/2021).

- 3Ibid. For the Integrated Operating Concept 2025, see: Integrated Operating Concept 2025, Ministry of Defence, 30/09/2020, http://bit.ly/ioc2025 (found: 14/06/2021).

- 4See: Andrew Foxall, ‘How Russia positions the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/35AzaH8 (found: 14/06/2021); Matthew Henderson, ‘How the Chinese Communist Party ‘positions’ the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 22/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3nizzWq (found: 14/06/2021); and Philip Shetler-Jones, ‘How allies ‘position’ the United Kingdom, Council on Geostrategy, 06/05/2021, https://bit.ly/2TJpibc (found: 14/06/2021).

- 5Russia was identified as an ‘acute direct threat’ and the PRC was identified as a ‘systemic competitor’ in the Integrated Review. See: ‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 16/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 14/06/2021).

- 6See: Philip Shetler-Jones, ‘How allies ‘position’ the United Kingdom, Council on Geostrategy, 06/05/2021, https://bit.ly/2TJpibc (found: 14/06/2021).

- 7Andrew Foxall, ‘How Russia positions the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/35AzaH8 (found: 14/06/2021).

- 8Matthew Henderson, ‘How the Chinese Communist Party ‘positions’ the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 22/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3nizzWq (found: 14/06/2021).

- 9Philip Shetler-Jones, ‘How allies ‘position’ the United Kingdom, Council on Geostrategy, 06/05/2021, https://bit.ly/2TJpibc (found: 14/06/2021).

- 10Acheson’s exact statement was: ‘The attempt to play a separate power role – that is, a role apart from Europe, a role based on a special relationship with the US, a role based on being head of a “Commonwealth” which has no political structure, or unity, or strength – that role is about played out.’ See: Gavin Hewitt, ‘US-UK: Strains on a special relationship’, BBC News, 20/04/2016, http://bit.ly/uusoass (found: 14/06/2021).

- 11This point is expanded on thoroughly by Andrew Foxall. See: Andrew Foxall, ‘How Russia positions the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/35AzaH8 (found: 14/06/2021).

- 12See: Patrick Wintour, ‘David Cameron: UK may be a small island but it has the biggest heart’, The Guardian, 06/09/2013, http://bit.ly/dcumbasibihtbh (found: 14/06/2021).

- 13See: ‘Global Britain: delivering on our international ambition’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 13/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3q8VnWg (found: 14/06/2021).

- 14Boris Johnson, ‘G7 Summit is a chance to show the world our values’, 10 Downing Street, 10/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3cQkqYB (found: 14/06/2021).

- 15Theresa May, Speech: ‘PM speech to the Lord Mayor’s Banquet 2017’, 10 Downing Street, 13/11/2017, https://bit.ly/39uZRPR (found: 14/06/2021).

- 16Nigel Biggar and Doug Stokes, ‘How “progressive” anti-imperialism threatens the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 10/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3gKLGsM (found: 14/06/2021).

- 17According to the British Council, the number of Confucius Institutes expanded from 320 to 507 between 2013 and 2018, while the number of Russkiy Mir Foundations increased from 82 to 171 over the same period. See: John Dubber (ed.), ‘Soft power superpowers: Global trends in cultural engagement and influence’, British Council, 2018, https://bit.ly/35EInOy (found: 14/06/2021).

- 18Episode 1, House of Cards, BBC 1, 19/11/1990.

- 19For an excellent analysis of the deployment of HMS Defender (and HNLMS Evertsen) to the Black Sea, see: Mark Galeotti, ‘HMS Defender in the Black Sea: What to expect’, Britain’s World, 14/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3vJp2GG (found: 14/06/2021).

- 20For a good example of clear and unambiguous British narrative projection, see: ‘CSG21 in the Black Sea’ (Tweet), @smrmoorhouse, 14/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3vJwPUH (found: 14/06/2021).

- 21‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 16/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 14/06/2021).

- 22‘Xi Seeks “Lovable” Image for China in Sign of Diplomatic Rethink’, Bloomberg, 01/06/2021, https://bloom.bg/3xCzsZM (found: 14/06/2021).

- 23‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 16/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 14/06/2021).