Foreword

The Black Sea matters to us and to wider Euro-Atlantic security. Long before the renewed invasion of Ukraine last month, Russian aggression in the region began in Chechnya, continued with the invasion of Georgia (2008), and then the seizure of Crimea and the insurrection in the Donbas (2014).

I was the first British defence secretary to have to respond to this new area of threat: I sent the British Army in to train the Ukrainian forces, and I deployed the Royal Air Force for the first time to conduct air policing from Romania. Our Royal Navy destroyers also began a series of visits to Black Sea ports. We worked to persuade the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) that its southeastern quadrant was just as vulnerable as the Baltic states further north.

In this important Policy Paper, Alexander Lanoszka and James Rogers help us appreciate the true challenge that Russia’s current invasion now poses, not just for the region, but for our wider Euro-Atlantic security. Keeping the Black Sea open and free matters for Britain’s long-term maritime interests. For more than two centuries the region has been vital for our trading routes to the east, and each time it has been threatened, we have had to intervene.

The paper examines several scenarios but, however the war ends, we will need to step up again. Ukraine itself will require a massive international programme of reconstruction, and should be offered a clearer and faster path to proper integration with the Euro-Atlantic community.

The paper also suggests that Britain should play a bigger role, championing a new political grouping of all the Black Sea states including Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova, and Georgia. Some of the littoral states will need our help in building stronger defence systems. We could establish a joint naval force, as we have done with the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) for our northern friends, whether they are in NATO or not.

The renewed Russian attack on Ukraine is already forcing all of us to rethink our security: witness the debates now on German defence spending, the American commitment to NATO, even Swedish neutrality. But what is certain is that the Black Sea must never again be overlooked.

This stimulating paper should be read by all those – military officers, officials, parliamentarians – who care not just about Ukraine, but about our wider Euro-Atlantic security.

– Sir Michael Fallon

Secretary of State for Defence, 2014-2017

Executive summary

- The Kremlin’s renewed offensive against Ukraine has left the Black Sea region as a zone of conflict that the Kremlin now plainly seeks to dominate. The United Kingdom’s (UK) stake in the Black Sea region has been elevated as a result, calling for Her Majesty’s (HM) Government to adapt to, and shape, the new geopolitical reality.

- The Black Sea region now forms a central bulwark in Britain’s outer defence system in the Euro-Atlantic area and is essential for the UK’s ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific: any power controlling the Black Sea would be able to exert significant pressure on the key maritime communication lines from Europe to the Indo-Pacific.

- The UK’s humanitarian and military support for Ukraine since 2014 has done much to help Kyiv resist the Russian onslaught, as have recent HM Government efforts to deepen ties with Poland and Ukraine through the trilateral group.

- Insofar as conflict in the Black Sea region affects British interests, it is necessary to think about the region’s future. In this Policy Paper, we construct four potential scenarios for the region:

- Russia triumphant: Russia’s successful offensive sees it dominate the Black Sea and threaten other countries in the region, such as Moldova and Georgia.

- Russia contained: Russia gets bogged down in a protracted insurgency in Ukraine and employs brutal counterinsurgency tactics. The Black Sea remains a nervous region yet the Russian threat, whilst still acute, is manageable.

- Russia embittered: Russia’s invasion fails to achieve its objectives, yet effectively destroys Ukraine. Immense refugee flows to Black Sea states cause a humanitarian crisis, and maritime governance breaks down.

- Russia defeated: The Kremlin’s renewed offensive in Ukraine is thrust back, and the security of Ukraine and the Black Sea, and beyond that, the Euro-Atlantic, mostly assured.

- Although not equally likely, these four scenarios allow British strategists and policymakers to think about the future of the Black Sea region. Of the four, ‘Russia triumphant’ is the least desirable. While the war rages, HM Government should do everything in its power, beyond getting directly involved in the fighting, to assist the Ukrainian Government and prevent other countries from diplomatic meddling, which might empower the Kremlin and jeopardise a Ukrainian victory. There should be no misunderstanding as to what a triumphant Russia would entail for Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific security.

- Looking to the war’s aftermath – much of which is, of course, contingent on how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine proceeds – HM Government can already take steps in a manner that cuts across the three other scenarios to advance British and NATO interests – as well as those of Ukraine – in the Black Sea region:

- Gather and exchange lessons from the war: The war presents an important opportunity to gather and exchange lessons about Russian military capabilities. HM Government should convene a project to learn how Russia uses military force en masse as well as what Ukraine did well, or less well, in responding to it, and how the Kremlin might adjust operations in the future.

- Restore and uphold freedom of navigation and maritime law: Russia has acted with impunity in its assault on Ukraine. The UK and its allies ought to contemplate appropriate responses to adversaries infringing on maritime law and agreements such as the Montreux Convention. Such an exercise is vital to ensure freedom of navigation and uphold openness in the Black Sea region.

- Help Black Sea states deter existential threats: HM Government should assist NATO allies and partners surrounding the Black Sea to improve their military capabilities. Improved capabilities would complicate Russian targeting and threaten new costs if the Kremlin decides to attack its neighbours in the future.

- Empower and create new Black Sea ‘plurilateral’ initiatives: Working more with the governments of littoral states in the Black Sea region, HM Government should:

- Push ahead with the trilateral initiative with Poland and Ukraine.

- Convene a summit to bring together Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, Turkey and Ukraine to form a ‘Black Sea grouping’.

- Convene a Joint Naval Force (JNF) with a specific mandate to undertake patrols under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Montreux Convention.

- Prepare for the reconstruction of Ukraine: Insofar as the reconstruction of Ukraine will be a generational project, planning ahead cannot start too early. HM Government ought to apply diplomatic pressure to advance Ukraine’s European Union (EU) membership bid; prioritise Ukraine in its evolving international development strategy; and emphasise the importance of the Three Seas Initiative for Black Sea security and connectivity.

Map 1: The Black Sea region (March 2022)

1.0 Introduction

As Map 1 shows, Russia’s renewed military offensive against Ukraine, commencing on 24th February 2022, has thoroughly upended the uneasy strategic balance across the Black Sea. Once relatively peaceful, if not especially prosperous, the Black Sea region has become a zone of conflict that the Kremlin now plainly seeks to dominate. Russia’s government is determined to re-establish a sphere of influence in the region, where autocracy reigns, democracy is discredited, and might makes right. This unprovoked assault has thrust the Black Sea region, and Ukraine in particular, into the strategic limelight in the United Kingdom (UK).

It has not always been this way. The 2010 National Security Strategy (NSS) and Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) did not mention the Black Sea, Ukraine, or, for that matter, Georgia – a country that Russia invaded just two years before.1See: ‘A Strong Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The National Security Strategy’, HM Government, 18/10/2010, https://bit.ly/3DecM6c (found: 17/03/2022) and ‘The Strategic Defence and Security Review: Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty’, HM Government, 19/10/2010, https://bit.ly/3JJ7X7B (found: 17/03/2022). The combined 2015 NSS and SDSR also omitted mention of the Black Sea, though it did cite Ukraine several times – unsurprisingly, given that the review occurred shortly after the Kremlin annexed Crimea.2‘National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015’, HM Government, 23/11/2015, https://bit.ly/3JHZ26f (found: 17/03/2022). The 2021 Integrated Review – ‘Global Britain in a competitive age’ – noted the Black Sea only once. Admittedly, the associated Defence Command Paper – ‘Defence in a competitive age’ – referred to it five times, more times than the Baltic Sea, despite how Estonia and Poland have received significant British strategic support to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO).3See: ‘NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence 2022 Factsheet’, NATO, 02/2022, https://bit.ly/3qAZGeo (found: 17/03/2022) and ‘Boosting NATO’s presence in the east and southeast’, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, 28/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3E0GfjT (found: 17/03/2022); and ‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 16/03/2022) and ‘Defence in a competitive age: Defence Command Paper’, Ministry of Defence, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3LmXM97 (found: 17/03/2022). There was some interest in the region when Russia attacked Georgia in 2008 and annexed Crimea in 2014. Still, British strategists and policymakers have often seen the Black Sea region as little more than a periphery of the Euro-Atlantic theatre.

In light of the Kremlin’s renewed assault on Ukraine, the Council on Geostrategy has compiled this Policy Paper to focus on the Black Sea region – an area where the UK has growing stakes. Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine necessitates a more wide-ranging discussion of how the region matters to ‘Global Britain’, and how Her Majesty’s (HM) Government should adapt to, and shape, the new geopolitical reality. Although Russia has moved beyond the ‘grey zone’ to undertake bold conventional military operations against Ukraine, the UK does not need to respond in kind, which would risk nuclear war. Instead, Britain should embrace the ‘campaigning’ approach outlined in the 2020 Integrated Operating Concept and broaden its geostrategic presence in the region to reinforce the efforts of Ukraine – and other Black Sea countries – to defend themselves.4‘Integrated Operating Concept’, Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, 2020, https://bit.ly/ioc2025 (found: 17/03/2022).

We begin by outlining the UK’s evolving historical interests in the Black Sea theatre, before examining Britain’s renewed geostrategic posture with special reference to the Integrated Review and the Defence Command Paper, as well as the 2020 Integrated Operating Concept.5Ibid. Thereafter, we construct four potential scenarios which might fundamentally reshape the Black Sea region. For the sake of analytical simplicity, we construct these scenarios using a matrix with two axes: one accounts for the degree of Russian success or failure in Ukraine; the second accounts for the resulting political order derived from the Kremlin’s actions. Having delineated these scenarios, we evaluate the strategic impact that each would have on the Black Sea region, the Euro-Atlantic, and, ultimately, the UK, before concluding with a series of recommendations for HM Government.

2.0 Britain’s enduring interests in the Black Sea region

As an insular ‘seapower state’ adjacent to the European continent and dependent on access to its surrounding seas, the UK’s enduring geostrategic interest has been to uphold openness, both internationally and at sea.6For more on the concept of seapower states, see: Andrew Lambert, Seapower States: Maritime Culture, Continental Empires, and the Conflict that Made the Modern World (New Haven, Massachusetts: Yale University Press, 2018). Since most global trade occurs by sea, an open international order, alongside freedom of navigation, allows an archipelagic trade-oriented economy such as Britain’s to flourish because it creates predictability and reduces the risk of predation. Alternatively, large continental powers often seek to do the opposite: by ‘continentalising’ maritime spaces, they can reduce the influence of maritime powers or extract tribute when their ships pass into waters continental states claim as their own.7‘Continentalisation’ refers to the process whereby terrestrial powers attempt to close the sea and to incorporate it into their borders. Ibid, p. 320. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Britain identified the Black Sea region as integral to British interests: initially, because it provided a sea route to Persia that bypassed the Russian-controlled Caucasus; later, because, with the construction of the Suez Canal, the Black Sea could be used to exert pressure on the ‘Royal Route’ to the Middle East, Asia and Oceania.

Yet the geography of the Black Sea, which is sandwiched between Europe, Eurasia and the Middle East, and practically enclosed except for the narrow Dardanelles and Bosphorus, encourages geopolitical rivalry. Turkey and Russia both border the Black Sea, and the UK’s pervasive maritime presence, essential to uphold the openness of all European seas, substantiates competition. These three major powers have regularly fought one another to control access. In 1806, Britain warred with the Ottoman Empire to prevent France from closing the Black Sea, and in 1841 agreed to the London Straits Convention – closing the Dardanelles to all ships, including those from countries allied to the Ottoman Empire – out of fear that the Ottomans were incapable of ensuring the Black Sea remained open. Rivalry between Russia and the UK in the Black Sea has also been intense, culminating in the 1853-1856 Crimean War8.Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History (New York City: Picador, 2012).

The opening of the Suez Canal – establishing the ‘Royal Route’ – only accentuated the Black Sea’s significance in the UK’s geostrategic calculus; any country lording over the region would be able to push down into the Eastern Mediterranean, potentially threatening the UK’s newfound economic lifeline. Early in the 20th century, however, Britain’s naval reach began to wane as the Soviet Union and Turkey emerged. Turkey thwarted the Gallipoli Campaign during the First World War. At the same time, the encroachment of Soviet continental power – particularly during and after the Second World War – eventually encased the Black Sea on three sides. Only through Turkey’s inclusion in NATO in 1952, which the UK came to support, was access upheld.

Despite falling tensions in the Black Sea after the Cold War, the Kremlin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 gave way to a new round of ‘continentalisation’. Under cover of the Minsk Accords – from inception ‘a rotting corpse slumped over the conference table’9Mark Galeotti, ‘The Minsk Accords: Should Britain declare them dead?’, Council on Geostrategy, 24/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3ICl8Wx (found: 24/03/2021). – Russia consolidated control over Crimea and the Donbas. The Kremlin developed sly ‘boa constrictor’-like tactics to close off the Sea of Azov and nearby maritime spaces, allowing it to extend Russian influence over the Black Sea.10Ihor Kabanenko, ‘Freedom of Navigation at Stake in Sea of Azov: Security Consequences for Ukraine and Wider Black Sea Region’, The Jamestown Foundation, 06/11/2018, https://bit.ly/35kVMig (found: 28/03/2021). In turn, the Kremlin’s hand grew stronger in the Caucasus, thus putting more pressure on Georgia, as well as the Eastern Mediterranean, where Russia enjoyed a freer hand to meddle in Syria.

A strengthened Russia in the Black Sea region gains additional significance due to HM Government’s ambitions in the Integrated Review to ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific, where the UK aims to be ‘the European partner with the broadest and most integrated presence’ in the Indo-Pacific zone by 2030.11‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 16/03/2022). First, any power dominant in the Black Sea region would have extensive influence over the Eastern Mediterranean, which hosts British military facilities, and the critical ‘Royal Route’. Second, as competition between the United States (US) and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) intensifies, the US will likely refine its Euro-Atlantic commitments in order to allocate more resources to the Indo-Pacific. Underwriting Black Sea security will become more of a task for, and thus much more significant to, the UK.

Should Russia be allowed to consolidate its position in the Black Sea region, it would almost certainly strengthen its reach into the Eastern Mediterranean, potentially threatening key NATO allies’ interests in the Indo-Pacific, not least those of the UK (see Box 1). At the very least, NATO allies have a clear interest in preventing the Black Sea from becoming a Russian ‘lake’ or a Chinese franchise. Besides being connected to the Mediterranean Sea, developments in and around the Black Sea also bear on the Baltic Sea, not least as any failure on NATO’s part to show resolution in resisting Russian adventurism in one region may encourage challenges in the other.

2.1 British economic interests

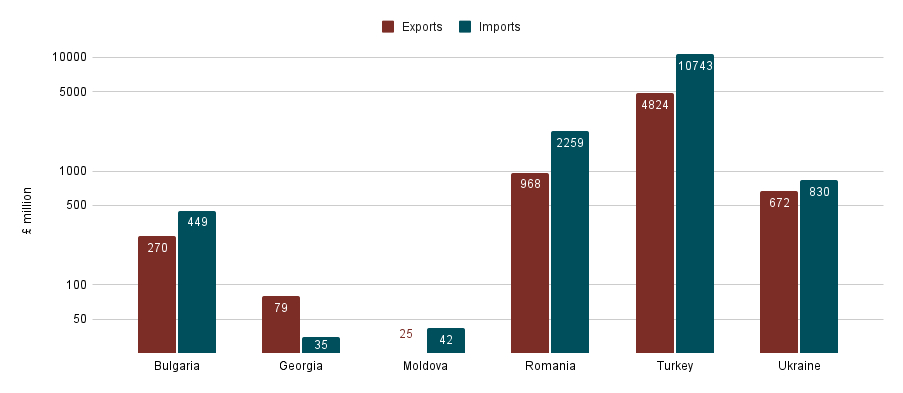

Beyond its geostrategic importance, the Black Sea region has additional economic significance.12Because Russia’s renewed offensive against Ukraine has undermined commercial activity between the UK and Russia, these calculations and statistics exclude Russia. As Graph 1 shows, Britain conducted £21 billion worth of bilateral trade with the region in 2021, making up 2.1% of the British economy’s total imports and 3% of its total exports.13These statistics are drawn from the Office for National Statistics. See: ‘UK Trade: January 2022’, Office for National Statistics, 11/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3DeMHnC (found: 17/03/2022). Those figures seem small, but as Graph 2 shows, trade with the region has steadily increased since the Soviet Union fell, particularly with relatively high-growth Ukraine and Turkey. More importantly, Black Sea states provide the UK, and the world, with a large share of critical commodities. For example, Ukraine provides a significant amount of Britain’s cooking oil, supplying 9% of total vegetable oil and fats imports and 12.5% of oil-seeds and oleaginous fruits imports – both significant shares. The volume of Ukrainian vegetable oil and fats imports coming into the UK has increased by 263% in the last five years, underpinning a growing British reliance on Ukraine for the product.

Given the significance of Ukraine’s agricultural output, conflict there may also have significant consequences for other theatres, particularly the Middle East and North Africa. For example, Egyptians consume approximately 37% of their calories from wheat.14Kibrom Abay et al., ‘The Russia-Ukraine crisis poses a serious food security threat for Egypt’, International Food Policy Research Institute, 14/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3iFXPR2 (found: 23/03/2022). Ukraine makes up roughly just over 10% of the global wheat market, and Egypt imports 25% of its wheat from Ukraine.15These statistics are drawn from the United Nations’ Comtrade Database. See: ‘Comtrade Database’, United Nations, 2022, https://bit.ly/3qGGyvw (found: 24/03/2022). Yemen, already in the midst of a civil war, also imports 14.5% of its wheat from Ukraine, with 31% having come from there in the past three months.16Ibid and ‘Yemen: Millions at risk as Ukraine war effect rocks region’, World Food Programme, 14/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3wGvfqT (found: 23/03/2022). Rising wheat prices and associated costs will almost certainly harm both Egypt and Yemen. Food insecurity fuelled protests in Egypt in 2010, arguably contributing to the so-called ‘Arab Spring’, which swept across the Levant and North Africa, with all of its associated consequences.

Graph 1: UK imports and exports to the Black Sea region 2021

Graph 2: Total trade value between the UK and Black Sea states, 1990-2020

3.0 Britain’s contemporary posture in the Black Sea

The UK’s ability to influence the Black Sea is conditioned by its geopolitical position: it is the only country with sovereign territories in three European locations – the British Isles, Gibraltar and the Sovereign Bases on Cyprus – which provides it access to, and a degree of control over, Europe’s maritime communication lines, which connect the continent to North America, Africa and the Indo-Pacific.17For more on the UK’s unique geostrategic position in Europe, see: Nicholas Spykman, America’s Strategy in World Politics (London: Transaction Publishers, 2008 [1942]), p. 98. The UK upholds this European geopolitical footprint with a unique set of national capabilities, which are underpinned by the world’s third-largest defence budget (and the largest in Europe).18‘Military Balance 2022: Further assessments’, International Institute for Strategic Studies, 15/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3uAmg89 (found: 13/03/2022). The Royal Navy, equipped with two supercarriers, nuclear attack submarines, and a fleet of escorts and auxiliaries, is the heaviest in Europe; it is also armed with a guaranteed second-strike nuclear capability, which is capable of inflicting grievous harm on any adversary.19See: ‘The UK’s nuclear deterrent: what you need to know’, Defence Nuclear Organisation, 22/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3Npr0Wz (found: 17/03/2022). With the British Army and Royal Air Force, Britain is forward-deployed broadly and extensively to NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP) in the Baltic and Black sea policing missions,20See: ‘NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence 2022 Factsheet’, NATO, 02/2022, https://bit.ly/3qAZGeo (found: 17/03/2022) and ‘Boosting NATO’s presence in the east and southeast’, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, 28/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3E0GfjT (found: 17/03/2022). while the UK’s cyber capabilities are world-leading in both defensive and offensive dimensions.21Julia Voo et al., ‘National Cyber Power Index 2020: Methodology and Analytical Considerations’, Belfer Centre, 09/2020, https://bit.ly/3DcGJn8 (found: 17/03/2022).

Unsurprisingly, Britain sees itself as Europe’s preeminent power and NATO’s foremost European guarantor. HM Government’s Integrated Review asserts not only that ‘the UK will be the greatest single European contributor to the security of the Euro-Atlantic area to 2030’, but also that ‘the UK will remain the leading European ally in NATO’.22‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 16/03/2022). Emphasis added. For this reason, Britain has been quick to emphasise threats to openness in the Euro-Atlantic area. Building on the 2015 NSS and SDSR, the Integrated Review highlights the ‘intensification’ of ‘geopolitical competition’ and pinpoints Vladimir Putin’s Russia as the ‘most acute direct threat’ to the UK and, by extension, NATO.23Ibid. The 2015 NSS and SDSR used the term ‘wider state competition’. See: ‘National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015’, HM Government, 23/11/2015, https://bit.ly/3JHZ26f (found: 17/03/2022). It claims that ‘Russia will be more active around the wider European neighbourhood’ – a reference to Russian ‘continentalisation’ around Europe’s maritime fringes – where most countries are smaller, weaker, and less capable of resisting the Kremlin’s will.24Ibid.

Insofar as the risk of nuclear escalation has not subsided, Britain intends to compete with peer and near-peer competitors, such as Russia, in the so-called ‘grey zone’ between ‘peace’ and ‘war’.25See: Nick Carter, Speech: ‘Dynamic security threats and the British Army’, Ministry of Defence, 23/02/2018, https://bit.ly/3tR5eU9 (found: 17/03/2022). In accordance with the 2020 Integrated Operating Concept, competing against such rivals on this ‘continuum of conflict’ requires a willingness and ability to constrain opponents by escalating and de-escalating across and through domains, as well as within them.26‘Integrated Operating Concept’, Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, 2020, https://bit.ly/ioc2025 (found: 17/03/2022). In part, this will involve an operating framework based on ‘constant campaigning’ to move ‘seamlessly from operating to war fighting’ and a ‘more persistent’ form of global engagement.27‘Defence in a competitive age: Defence Command Paper’, Ministry of Defence, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3LmXM97 (found: 17/03/2022). The military thus ‘will no longer be held as a force of last resort, but become more present and active around the world.’ It will aim to operate ‘below the threshold of open conflict’ to uphold British values, secure UK interests, and partner with friends and enable allies ‘in the Euro-Atlantic, the Indo-Pacific, or beyond.’28Ibid. As such, HM Government intends to use military power as a core component of British state power, not only to destroy or compel enemies, but also to dissuade or to deter geopolitical rivals by establishing a geostrategic presence and by making allies and partners more resilient.

3.1 Contemporary British engagement in the Black Sea region

Although the Integrated Review confirms that the UK will operate ‘across the Euro-Atlantic region’, it affirms that it will ‘focus on the northern and southern flanks of Europe’, where the threat from Russia is most severe. There, it states that Britain ‘will support collective security from the Black Sea to the High North, in the Baltics, the Balkans and the Mediterranean’.29Ibid. This mention of the Black Sea is the only one in the Integrated Review, however. As HM Government has focused on reinforcing NATO’s EFP in the Baltic, to which the UK is the largest contributor, it has also moved, albeit in a novel way, to shore up security in the Black Sea region, to the extent that the region now forms a central bulwark in Britain’s outer defence perimeter.

Indeed, although the UK’s new operating model – ‘campaigning’ – was outlined in the 2020 Integrated Operating Concept, it has arguably been hammered out in the Black Sea theatre. Since Russia’s offensive against Ukraine began in 2014, the British Army set up Operation ORBITAL, successfully training over 22,000 personnel to enhance the resilience and fighting power of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Meanwhile, the Royal Air Force sent Typhoon fighters to Romania as part of NATO’s Black Sea air policing mission. And with its interest in maritime openness, the UK has paid particular attention to Russia’s naval activities in the Black Sea. The Defence Command Paper explains:

We will work with other partners in the Black Sea region, notably Bulgaria, Greece, Romania and Turkey, to ensure freedom of navigation and security. As part of this we will continue to exercise our freedom to operate in the Black Sea, in strict accordance with the Montreux Convention, both through NATO and on stand-alone deployments.30Ibid.

With 11 vessels deployed since 2017, the Royal Navy has established a more persistent naval presence in the region than in previous years.31The Black Sea has seen Royal Navy warships deployed 11 times since 2014: HMS Chiddingford (2014), HMS Duncan (2015, 2017, 2018, and 2019), HMS Daring (2017), HMS Echo (2018-2019), HMS Dragon (2020), HMS Trent (2021) and HMS Defender (2021). Indeed, in April 2021, as part of the maiden voyage of the Carrier Strike Group, HMS Defender was deployed to challenge the Kremlin’s illegal claims on maritime spaces around Crimea.32See: Molly McKew, ‘HMS Defender goes for a pleasure cruise through Russian narrative warfare in the Black Sea’, Great Power, 23/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3tKsl2z (found: 13/03/2022). Additionally, the UK has provided £1.7 billion in loans to help develop Ukraine’s navy, both in terms of Black Sea bases and new warships.33For a good overview of this agreement, see: Eren Waitzman, ‘UK-Ukraine Credit Support Agreement’, House of Lords Library, 16/12/2021, https://bit.ly/36A6PEH (found: 28/03/2021).

Box 1: Strategic ties between the UK and countries in the Black Sea region

Bulgaria

- Fellow NATO ally (2004)

- Support for the Tailored Forward Presence (2016-)

- Expanding strategic partnership (2014-)

- Agreement concerning the Protection of Classified Information (2013)

Georgia

- Strategic Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (2019)

- Wardrop Strategic Dialogue (2014-)

Moldova

- Strategic Partnership, Trade and Cooperation Agreement

Romania

- Fellow NATO ally (2004)

- Support for the Tailored Forward Presence (2016-)

- Strategic Partnership (2003-)

Turkey

- Fellow NATO ally (1952)

- Free Trade Agreement (2020)

- Framework Agreement on Military Cooperation (2019)

- Security Agreement concerning the Protection of Defence Classified Information (2016)

Ukraine

- Poland-Ukraine-UK trilateral (2022)

- Framework Agreement on Official Credit Support for the Development of the Capabilities of the Ukrainian Navy (2021)

- Political, Free Trade and Strategic Partnership Agreement (2020)

- Operation ORBITAL (2015)

As Box 1 shows, beyond these forward deployments and ‘campaigns’, HM Government has actively cultivated British bilateral relations with countries surrounding the Black Sea. It has deepened Britain’s relationship with Ukraine. Many Ukrainian foreign policy thinkers now consider the UK to be the second most friendly country in the world to Ukraine.34‘Annual Survey of Ukrainian Experts’, Ukrainian PRISM, 24/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3iW753L (found: 17/03/2022). This cooperation intensified in 2021 when the two powers signed a ‘Political, Free Trade and Strategic Partnership Agreement’, which paved the way for the UK to provide Ukraine with Brimstone naval missiles, NLAW anti-tank weapons and the Starstreak surface-to-air missile system. Ukraine is also central to Britain’s attempts to develop more novel forms of cooperation which mirror those it has developed in Northern Europe, such as the Joint Expeditionary Force. In mid-February 2022, Liz Truss, the Foreign Secretary, announced the formation of a new trilateral grouping composed of the UK, Poland and Ukraine to facilitate cooperation in four priority areas: coordinating the International Crimea Platform; cyber security; energy security; and strategic communications to counter disinformation – ostensibly from Russia.35Poland may not be in the Black Sea region itself, but nevertheless has importance given its positioning between that body of water and the Baltic Sea. Poland has provided the main logistical hub for arms shipments intended to help Ukraine fight Russia. See: ‘United Kingdom, Poland and Ukraine foreign ministers’ joint statement’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 17/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3NnbxpX (found: 17/03/2022).

4.0 Russia’s Black Sea offensive

The threat Russia posed to the Black Sea region moved out of the ‘grey zone’ on 24th February 2022 when the Kremlin launched a fully-fledged invasion of Ukraine. This renewed military offensive has sought to decapitate the Ukrainian Government of Volodymyr Zelenskyy, eliminate Ukrainian democracy, and destroy the economic foundations of Ukrainian society. The Kremlin’s broader geostrategic objectives, beyond the absorption of Ukraine into a Russian sphere of influence, are opportunistic. Although the Putin regime may have a strategic vision – restoring Russia to the status of an imperial power in Eurasia and particularly in Eastern Europe – its lack of material capability forces it to adopt an ‘anti-systemic’ approach.36For more on the Kremlin’s approach, see: James Rogers and Alexander Lanoszka, ‘A ‘Crowe Memorandum’ for the twenty-first century’, Council on Geostrategy, 02/03/2021, https://bit.ly/385eN9q (found: 17/03/2022). This involves spoiling the prevailing Euro-Atlantic order or preventing neighbours from becoming part of it. In Ukraine, as of writing, the Russian offensive pushes slowly forward despite significant setbacks and stiff Ukrainian resistance.

4.1 Scenarios

At this stage, how Russia’s offensive in Ukraine will pan out is impossible to predict because too many variables are in play. Insofar as the war may drag on for months or even years, the Kremlin has condemned the Black Sea region to violent conflict, at least for the short term. Given that Russian victory is far from certain, how the Black Sea region will look in the medium term (next five years) is not known, to say nothing of the longer-term (next ten years). That said, we can still identify the key outcomes that are likely to shape the Black Sea region. In so doing, we can narrow down, and construct using a matrix, scenarios that may have a significant geopolitical impact on British and allied interests. These scenarios will not be accurate glimpses of how the region will look in five to ten years from now. Still, they contain sufficient detail to allow for the identification of geopolitical possibilities.37See: Charlie Edwards, ‘Futures thinking (and how to do it…)’, Demos, 2005,https://bit.ly/3iCnLNd (found: 15/03/2022). Moreover, the scenarios are not equally probable; given the fluid dynamics that characterise the war today, we do not assign likelihoods to them, though we do assign relative desirability.

The key to this exercise is Russia’s ability to prevail. If despite initial failures the Kremlin achieves its geopolitical objectives in Ukraine, Russia will enjoy a position of supreme dominance – even hegemony – over the Black Sea region, which may further allow the Kremlin to consolidate its hand in Southeastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean. If it fails, Russia will be much weakened. Ukraine could perhaps come out of the struggle stronger and more interconnected with the Euro-Atlantic than before the war. In this sense, Russian power – and its ability to succeed against Ukrainian opposition – is the most important variable for constructing the matrix. At the same time, what level of political order – or chaos – might prevail in the Black Sea region is vital to consider. For example, the Kremlin may find military success but have difficulties imposing its rule within Ukraine and perhaps Russia itself because of sanctions and popular unrest. This dimension forms the second axis for the matrix.

From this matrix, we can delineate four scenarios for the Black Sea region:

Below, we construct these four scenarios in more detail. Each would have significant geopolitical consequences for Ukraine and the broader Black Sea region, as well as the Euro-Atlantic order. We also assess how these scenarios might affect British strategic interests with reference to the following concerns:

- What would the scenario’s impact be on British partners and allies in the Black Sea region?

- What impact would the scenario have on British commercial activities in the Black Sea region?

- What would the impact of the scenario be on freedom of navigation and economic openness in the Black Sea region?

- To what extent would the scenario threaten NATO?

- What impact, if any, would the scenario have on Britain’s force posture in Europe, particularly in relation to the Black Sea region?

- To what extent would the scenario jeopardise the military dimension of Britain’s ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific?38Using the following adjectives – extreme, severe, significant, moderate, limited, low or inconsequential – we specify the extent to which these concerns would affect British interests.

Of course, these concerns are highly linked. The correlation between them, however, will not be perfect. Even within the scenarios themselves, there is plenty of room for contingency – ‘wildcards’ – which we discuss towards the end of this section.

4.1.1 Russia triumphant

In our first scenario, the Kremlin prevails. Despite stiff resistance from the Ukrainian Armed Forces, the renewed Russian offensive against Ukraine eventually succeeds and the democratic government led by Zelenskyy falls. Russia annexes all of Ukraine east of the Dnipro River and renders the rest of the country a puppet state under the Kremlin’s control. Ukrainians, morally and economically drained by the fighting and devastation, submit to the new order. The Kremlin secures its position, which boosts the authority and popularity of Putin’s regime within Russia, enabling it to dominate the Black Sea region.

Geopolitical impact on the Black Sea region: A victorious Russia, however depleted, would be able to position itself as the dominant power in the Black Sea, over which the capture of key Ukrainian cities in the south would cement its hold. An emboldened Russia may threaten other Black Sea countries, such as Moldova or Georgia. Any independent Ukraine that might somehow re-emerge in the future would be hobbled severely by its lack of access to its former ports and the maritime communication lines that they serve. Russia would thus be able to ‘continentalise’ the Black Sea even though the Montreux Convention – should an emboldened Russia still adhere to it – would still limit its ability to project naval power directly into the Mediterranean.

Geopolitical influence on the Euro-Atlantic order: Euro-Atlantic security would be jeopardised most severely in this scenario. If Russia succeeds in defeating Ukraine, then its position in Eastern Europe would be significantly strengthened. The Kremlin would end its renewed assault on Ukraine with far more military mass in the region than it did before 2021, not least because Belarus would also be suborned. Of course, success could still be very costly for Russia: it would still need to come up with the funds necessary to maintain the vassalage of Ukraine and to repair itself amid the massive sanctions imposed upon it. For countries on NATO’s northeastern flank, the damage inflicted on the Russian economy may not provide much assurance: the Soviet Union too was devastated after the Second World War but it still had the wherewithal to dominate Eastern Europe and to pose a severe threat to Western Europe for several decades.

What would a triumphant Russia mean for Britain?

| Threat to allies and partners surrounding the Black Sea | Extreme |

| Impact on British commercial activity in the Black Sea | Severe |

| Ramifications for freedom of navigation in the Black Sea | Extreme |

| Threat to NATO | Severe |

| Impact on British force posture in Europe | Severe |

| Impact on the Indo-Pacific ‘tilt’ | Extreme |

For Britain, this scenario is very bleak: local allies and partners would face a confident, bossy and imperious Russia, while freedom of navigation and maritime law would be under greater duress, and, due to sanctions, commercial opportunities would significantly shrink. A Russia in control of Ukraine could pose an even more serious terrestrial threat for neighbouring Poland and Romania, to say nothing of Moldova and Georgia, compelling the UK to focus much more on the Euro-Atlantic than anticipated even by the Integrated Review and the Defence Command Paper. The UK would have to put more stock in the British Army and Royal Air Force than what the Defence Command Paper envisioned to bolster NATO’s ability to deter and defend, jeopardising the UK’s ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific. Having significantly strengthened its hold over Ukraine, and by extension, boosting its power in the Black Sea, Russia would be well-positioned to expand its influence into the Eastern Mediterranean. If successful, it would be able to threaten, directly or indirectly, the ‘Royal Route’ to the Indo-Pacific.

4.1.2 Russia contained

Russia succeeds in its conventional military operations against Ukraine, but gets bogged down in a protracted insurgency. Fanned on by assistance from the Euro-Atlantic democracies, this insurgency prevents Russia from consolidating control over a hostile population. Russia’s control of the Black Sea falls short of what would have been the case had its victory over Ukraine been decisive, but the security ramifications are extensive. As it vies for supremacy in Ukraine and attempts to reconstitute its military power, Russia would remain a major strategic challenge which demands containment rather than engagement strategies from the Euro-Atlantic democracies. In addition, the protracted humanitarian crisis that resulted from Russia’s initial invasion and counterinsurgency would continue to destabilise countries in Central and Northeastern Europe.

Geopolitical impact on the Black Sea region: Although Russia’s invasion of Ukraine would see the predominant use of conventional military tactics in its initial phases, the eventual emergence of a Ukrainian insurgency would put an even greater premium on counterinsurgency warfare. Already an international pariah, the Kremlin would not hold back: its methods would horrify countries worldwide and cause additional refugee flows. Although fighting the Ukrainian resistance would constrain Russia, it would nevertheless continue to make countries adjacent to the Black Sea nervous. It is hard to see how commercial activity in and around the Black Sea, including maritime movements, would be unimpeded under such circumstances. Maritime governance would be under stress because the Black Sea would be the site of continued fighting and instability, eroding maritime law and norms.

Geopolitical influence on the Euro-Atlantic order: Although the Euro-Atlantic would fare better than if Russia prevailed decisively in Ukraine, its security would nevertheless remain jeopardised. The impact of the Ukrainian insurgency would be felt far and wide and would almost certainly continue to spill over. In an attempt to hit back at the Euro-Atlantic democracies for fuelling the Ukrainian resistance movement, the Kremlin would likely employ greater ‘grey zone’ warfare. This would force NATO to remain on high alert, though some allies – further from the Black Sea region – may adopt a more emollient stance towards Russia, which the Kremlin would probably exploit.

What would a contained Russia mean for Britain?

| Threat to allies and partners surrounding the Black Sea | Significant |

| Impact on British commercial activity in the Black Sea | Significant |

| Ramifications for freedom of navigation in the Black Sea | Moderate |

| Threat to NATO | Moderate |

| Impact on British force posture in Europe | Moderate |

| Impact on the Indo-Pacific ‘tilt’ | Limited |

For Britain, a contained Russia would remain ‘an acute and direct threat’ but it would be more manageable than one where the Kremlin triumphs. The UK and other Euro-Atlantic allies would not perceive as strong a need for a significant ground presence as if Russia would decisively prevail in Ukraine. Still, NATO would probably need to deploy lighter forces (such as engineers) to assist with the refugee flows and potential Russian or Belarussian ‘grey zone’ tactics. While this would not significantly affect the UK’s ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific, it may have ramifications for the country’s European force posture.

4.1.3 Russia embittered

Another scenario involves Russia and Ukraine having fought so hard that they both effectively lose. In this scenario, the renewed Russian invasion fails to achieve its political objectives due to the tenacity of the Ukrainian Government and Armed Forces. As the Kremlin becomes more desperate, it deploys a combination of large thermobaric and chemical weapons to shock the Ukrainian Government and force its submission. It also uses defoliants to disrupt Ukrainian agriculture, particularly rapeseed production in Western Ukraine. This leaves the centres of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv, and Odesa as burnt-out shells and undermines Ukrainian agricultural production – critical for Kyiv’s ability to resist. Many Ukrainians die, but their resistance to Russia grows. Unable to prevail in Ukraine, the Kremlin begrudgingly sues for peace; it surrenders control over the so-called ‘People’s Republics’, but holds onto Crimea and even parts of Donetsk and Luhansk. Primarily destroyed, Ukraine has become a lawless zone of chaos.

Geopolitical impact on the Black Sea region: Although the Kremlin’s offensive eventually failed, millions of refugees continued to flee Ukraine, many to Moldova and Romania, putting immense pressure on their respective governments. Facing one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes in European history, NATO allies would need to respond to stabilise their southeastern flank. As commercial activity is severely hampered and maritime governance breaks down, regional states may need to prepare for potential pirate activity in the Sea of Azov and around Ukraine’s broader coastline.

Geopolitical influence on the Euro-Atlantic order: The resulting state weakness in Russia and Ukraine would create unique risks for the Euro-Atlantic region. The ongoing humanitarian crises would mean major outflows of Ukrainian refugees or, in the case of Belarusian and Russian citizens, asylum seekers. Not only would such outflows require military assistance to the affected parties, but they could reignite the populism seen in Europe in the mid-2010s as social services strain and job competition intensifies. While Russia may be sufficiently weakened to the extent that it no longer poses a major military threat to neighbouring countries, to say nothing of NATO, fears may persist over the command and control of its large nuclear arsenal, not unlike after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

What would an embittered Russia mean for Britain?

| Threat to allies and partners surrounding the Black Sea | Moderate |

| Impact on British commercial activity in the Black Sea | Significant |

| Ramifications for freedom of navigation in the Black Sea | Moderate |

| Threat to NATO | Minor |

| Impact on British force posture in Europe | Limited |

| Impact on the Indo-Pacific ‘tilt’ | Minor |

For Britain, with an embittered Russia the Black Sea region would become even more anarchic than what had been the case before the invasion of Ukraine. Ukraine would be unable to reconstitute its navy, whereas Russia could still have the naval assets to play a spoiler role, so long as it is able to maintain them. Freedom of navigation and maritime law would be under the greatest pressure in areas adjacent to Ukrainian and Russian shores. Other actors would be ascendant. Turkey would be an even stronger power in the Black Sea, and the PRC may move in to pick up the pieces at Russia’s expense. However, instability would define the region, not least because of the sustained humanitarian crisis that the war precipitated. Along with its Euro-Atlantic partners, the UK may be called upon to provide or contribute ground forces to a stabilising or humanitarian response force. The impact that this might have on the UK’s broader geostrategic interests – including the Indo-Pacific ‘tilt’ – would be manageable or limited.

4.1.4 Russia defeated

In this scenario, Ukraine, supported by the Euro-Atlantic democracies, eventually gains the upper hand over Russia. Under robust economic sanctions, the Kremlin sues for peace and surrenders control of the so-called ‘People’s Republics’ in Donetsk and Luhansk – areas Ukraine has retaken – but clings tenaciously to Crimea. Ukraine surrenders sovereignty of Crimea in exchange for fast-tracked entry into the EU and NATO. Kyiv also receives an extensive financial assistance and development package from the UK, US, Canada and the EU to help stabilise the Ukrainian economy and enable post-war reconstruction.

Geopolitical impact on the Black Sea region: For the Black Sea region itself, the resulting security environment – the most benign of all the scenarios – would permit greater cooperation, as Russia would be less able to dominate or disrupt the prevailing order. If Ukraine could upgrade its status vis-à-vis the EU, the Three Seas Initiative would gain even more importance as it could become a critical vector that allows Ukraine to rebuild its economy and to enhance its energy independence, while assisting with its EU membership bid. For their part, Georgia and Moldova would become less susceptible to Russian influence and thus realign themselves more closely with the Euro-Atlantic community.

Geopolitical influence on the Euro-Atlantic order: In the event of a clear Russian defeat, the security of the Euro-Atlantic order would be mostly assured. Russia would face an uphill battle in its efforts to rebuild its economy and revive its military. It may even need international assistance to provide basic services and restore order. At least through the medium term, international terrorism and the rise of the PRC would receive greater priority as the pacing geostrategic issues that dominate the Euro-Atlantic agenda. Of course, concerns about Russia would not necessarily disappear because of its military defeat – its nuclear arsenal would remain intact, for example. However, its capacity for mischief would be much weakened. NATO’s northeastern flank would be even stronger thanks to the influx of new investment for European defence – not least from Poland and Germany – that Russia’s invasion helped precipitate.

What would a defeated Russia mean for Britain?

| Threat to allies and partners surrounding the Black Sea | Limited |

| Impact on British commercial activity in the Black Sea | Moderate |

| Ramifications for freedom of navigation in the Black Sea | Minor |

| Threat to NATO | Limited |

| Impact on British force posture in Europe | Minor |

| Impact on the Indo-Pacific ‘tilt’ | Minor |

For Britain, this scenario would allow HM Government to build closer bilateral relations with Ukraine and develop the trilateral group between Poland, Ukraine and the UK. Turkey would emerge an even stronger ally, given its growing defence-industrial ties with Ukraine and the laudable performance of the TB2 Bayraktar drones. Countries in the region might restore, even deepen, some of the maritime governance that had withered away after 2014 when Russia seized Crimea and began to militarise that peninsula with a mixture of defensive and offensive systems. Because Russia would be unable to ‘continentalise’ the Black Sea for the foreseeable future, the UK could still rely on using air and naval assets to extend military support to allies and partners, including Romania and Bulgaria, as it has already. This permissive environment would allow the UK to pursue its ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific with greater lee-way Russia’s ‘acute’ and ‘direct’ would be much reduced.

4.2 Potential ‘wildcards’

The futures outlined above are heuristic devices for thinking about how a range of outcomes relating to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could affect British and allied interests. However, much is contingent given the number of variables at play. Four are worth highlighting precisely because they can either exacerbate the worst elements or attenuate the best aspects of each scenario.

- The sustainability of NATO cohesion: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has incited major investments in defence across the alliance and new multinational deployments along the Eastern flank. In the spring of 2022, NATO is very unified. Yet alliance cohesion may weaken as the war draws on or whether some wish to engage in unilateral accommodation of Russia, for whatever reason. Strategies of containment may be strained again if cracks in NATO resurface over, for example, sanctions and Russian natural gas.

- Turkey’s international strategy: Turkey has supplied Ukraine with combat-effective TB2 Bayraktar drones and expressed diplomatic support for Kyiv throughout the war. However, questions about its overall reliability as a NATO ally might persist, especially if it decides to soften its démarche towards Russia. Such a change may be out of step with its recent competitive strategy, whether in Libya, the Caucasus, or elsewhere. Still, it cannot be ruled out considering that Turkey has leveraged its NATO role to extract concessions on issues relating to its Middle Eastern interests.

- Russian nuclear brinkmanship: Considering its hardware and manpower losses in Ukraine, the Kremlin’s defence establishment and political leadership may lean more on nuclear weapons in crisis diplomacy with NATO regardless of success or failure in Ukraine. It could play greater nuclear brinkmanship in order to wrest concessions, whether with respect to the Black Sea region or else. This willingness may stem from how the Kremlin believes nuclear blackmail works to its advantage, putting a premium on how NATO responds at the outset to Russian nuclear signalling.

- Russian domestic politics: Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine will almost certainly discredit Putin and his regime, possibly setting in train enough political upheaval that new rulers come to power. A regime espousing liberal democratic principles would be most welcome for Britain and the Euro-Atlantic community. Frictions might persist between Russia and NATO, but political liberalisation within Russia itself might lessen the impact and salience of those disagreements. Alternatively, politicians even more hardline than Putin could take power and still have revanchist ambitions towards Black Sea countries, even NATO, whatever the result of the invasion.

5.0 Conclusion

In a few short weeks, the Black Sea region has been transformed from an anarchic environment to a crisis zone. The Kremlin has proven its willingness to escalate beyond the ‘grey zone’ by launching a fully-fledged invasion to decapitate the Ukrainian Government. There should be no misunderstanding about the extent to which a triumphant Russia would ‘continentalise’ the Black Sea, further erode Euro-Atlantic security, and force ‘Global Britain’ to focus more on the defence of Europe at the expense of its broader interests. If Russia succeeds in the conventional phase but gets tied down because of an insurgency, its containment should be easier, but NATO disagreements on how to go about it might widen. If both sides – Ukraine and Russia – effectively lose, the resulting instability and human suffering would create uncertainty that would roil the larger region for the years to come. If Russia fails decisively in Ukraine, then the future of the Black Sea region may be brighter, even if Ukraine suffers in the interim.

5.1 Policy recommendations

Although the Kremlin has escalated vertically out of the ‘grey zone’, the UK has no reason to respond in kind. While the war rages, HM Government should do everything in its power, beyond getting directly involved in the fighting, to ensure that the Kremlin fails (or at least so that it does not triumph). So long as the Ukrainians are willing to resist the aggressor, the UK should ramp up sanctions on Russia’s kleptocracy and provide Ukraine with financial help and whatever weapons and other forms of military assistance it needs. It should also apply pressure – even public pressure – on allies and partners who might seek to compel the Ukrainians to end the conflict, particularly on unfavourable terms, or by providing a premature ‘off-ramp’ for the Kremlin. This means taking a firm line if the Kremlin requests ‘peace talks’, particularly if they are nothing more than a ruse to undercut the Ukrainians and secure a strategic advantage.

Looking beyond the prospect of a triumphant Russia, much still depends on how the renewed invasion of Ukraine proceeds. Yet it is not too early to think about the post-war environment; not only does the future need to be shaped now, but ‘campaigns’ launched now would help to prevent the Kremlin from again seizing the initiative and writing the future unimpeded. Besides viewing the Black Sea region as a distinct geostrategic space, HM Government should consolidate its recent success in strategic thought leadership and narrative projection. Accordingly, it would do well to take steps in a manner which cut across the three remaining scenarios to advance British and NATO interests – as well as those of Ukraine:

- Gather and exchange lessons from the war: Russia embarked on a large-scale and high-intensity military operation that broke with much of its stated military doctrine. Meanwhile, beyond its successes in the information domain, Ukraine, for its part, offered far more capable kinetic resistance than most observers expected of it – especially during the first few weeks of the fighting. As such, the war presents an important opportunity to gather and exchange lessons about Russian military capabilities and force employment among multiple vectors of operation. HM Government should convene a project to learn how Russia uses military force en masse as well as what Ukraine did well, or less well, in responding to it. This process should also consider how the Kremlin might adjust its operations in the future, and how the UK could ‘campaign’ against it.

- Restore and uphold freedom of navigation and maritime law: Throughout its renewed assault on Ukraine, Russia has acted with relative impunity, having attacked civilian ships with little consequence while ships belonging to the littoral NATO Black Sea members remain in port. Early in the war, confusion abounded as to whether Turkey would close the Dardanelles and Bosphorus to Russian warships, and how such a closure might affect conflict dynamics or lead to escalation. Local allies and partners can no longer take for granted that malign actors like Russia would abide by the Montreux Convention and other maritime laws. Accordingly, the UK and its allies and partners ought to contemplate what might happen if adversaries discount these agreements and what the appropriate responses would be. Such an exercise is important to ensure freedom of navigation in the region and prepare for worst-case scenarios that might see maritime law wholly undermined.

- Help Black Sea states deter existential threats: HM Government should assist NATO allies and partners surrounding the Black Sea to improve their military capabilities regardless of Russia’s near-term military performance. Considering the distances involved in the Black Sea and adjacent regions, enhancing local militaries with theatre-range strike capabilities could help deter the Kremlin by holding Russian forces directly at risk from greater distances. Anti-ship missiles would be especially useful to thwart Russian military operations at sea; even those with shorter ranges would be useful for negating the Russian Navy’s advantages in the Black Sea littorals. These capabilities would complicate Russian targeting and threaten new costs if the Kremlin decides to attack neighbours again.39Luis Simón and Alexander Lanoszka, ‘The Post-INF European Missile Balance: Thinking About NATO’s Deterrence Strategy’, Texas National Security Review, 3:3 (2020), pp. 12-30. As local NATO allies have refrained from patrolling their own waters for lack of surface ships, the UK should encourage and assist them in developing those capabilities so they are not similarly hamstrung in the future.

- Empower and create new Black Sea ‘plurilateral’ initiatives: Regardless of how the Kremlin’s military operations unfold, HM Government ought to intensify cooperation with the governments of littoral states in the Black Sea region. An observation made all too commonly about them is that differences in their threat assessments and capabilities have undermined local collective action. Russia’s actions against Ukraine underscore the need for the other Black Sea countries to overcome their disagreements and work more effectively together to advance their shared interests. With the Joint Expeditionary Force with the Baltic and Nordic nations, AUKUS with Australia and the US, and the trilateral with Poland and Ukraine, the UK has shown itself to be flexible and creative in forming new ‘plurilateral’ arrangements to boost regional cooperation and security. Consequently, HM Government should:

- Push ahead with the trilateral initiative with Poland and Ukraine, which the three countries announced in February 2022, expanding the initiative to focus on assisting Ukraine after the war;

- Convene a summit to bring together Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, Turkey, and, of course, Ukraine, to form a ‘Black Sea grouping’. With British support, this group – mixing NATO allies and non-NATO partners – could work together to boost regional security and to resist Russian aggression through the development of a Common Black Sea Strategy;

- Convene a Joint Naval Force (JNF) with a specific mandate to undertake patrols in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Montreux Convention to uphold the maritime interests of Black Sea stakeholders and to resist future Russian aggression, both in the ‘grey zone’ and outside of it. Potentially headquartered in Ukraine after the war has ended and drawing inspiration from the Joint Expeditionary Force, the JNF could include regional countries as well as extra-regional powers, such as France, Germany and the US, which could contribute aerial and naval assets.

- Prepare for the reconstruction of Ukraine: However the war ends, the impact on Ukrainian society will be immense. After only three weeks of fighting, an estimated 6.5 million Ukrainians have been displaced in their own nation, and over three million have already fled to neighbouring countries.40Jamey Keaten, ‘United Nations says 6.5 million people have been displaced inside Ukraine’, PBS News Hour, 18/03/2022, https://to.pbs.org/3wWmGIP (found: 18/03/2022). Thus, almost a quarter of Ukrainians have been uprooted; their lives destroyed. The Ukrainian economy is in ruins, threatening the global wheat supply, particularly in relation to the volatile Middle East and North Africa. Insofar as the reconstruction of Ukraine will be a generational project, planning ahead cannot start too early. HM Government should apply diplomatic pressure to advance recognition of Ukraine’s membership bid with the European Union (EU), which Zelenskyy has made a national priority.41See: Benjamin Tallis, ‘Drop the excuses and embrace Ukraine’, Britain’s World, 22/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3tI9sgI (found: 23/03/2022). It should also consider prioritising Ukraine (and the countries which depend on Ukrainian agriculture) in its evolving international development strategy; greater assistance for Ukraine was one of the ambitions Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister, had when merging the Department for International Development into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.42See: Boris Jonhson, ‘Global Britain’, Hansard, 16/06/2020, https://bit.ly/3JLiBdM (found: 25/03/2022).

About the authors

Dr Alexander Lanoszka is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Waterloo, Canada and an Ernest Bevin Associate Fellow in Euro-Atlantic Geopolitics at the Council on Geostrategy. He has previously taught at City, University of London, and was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Dickey Centre for International Understanding at Dartmouth College, and a Stanton Nuclear Security Postdoctoral Fellow at Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Security Studies Programme. Dr Lanoszka has worked for the United States Department of Defence and has consulted for Global Affairs Canada. He holds a PhD in Philosophy and an MA in Politics, both from Princeton University.

James Rogers is Co-founder and Director of Research at the Council on Geostrategy, where he specialises in the connections between Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific geopolitics and British strategic policy. Previously, he held positions at the Henry Jackson Society, the Baltic Defence College, and the European Union Institute for Security Studies. He has been invited to give oral evidence at the Foreign Affairs, Defence, and International Development committees in the House of Commons. He holds an MPhil in Contemporary European Studies from the University of Cambridge and an award-winning BSc Econ (Hons) in International Politics and Strategic Studies from the University of Wales, Aberystwyth.

Acknowledgments

The Council on Geostrategy would like to express appreciation to Ferrexpo PLC for sponsoring the publication of this Policy Paper.

Equally, the authors would like to thank Patrick Triglavcanin, Research Assistant at the Council on Geostrategy, for his support in drafting this Policy Paper. In addition, they would like to thank the officials and experts who attended the research workshop held on 21st March to consider the ideas contained in this Policy Paper.

Disclaimer

This publication should not be considered in any way to constitute advice. It is for knowledge and educational purposes only. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Council on Geostrategy or the views of its Advisory Council.

No. SBIPP07 | ISBN: 978-1-914441-20-2

- 1See: ‘A Strong Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The National Security Strategy’, HM Government, 18/10/2010, https://bit.ly/3DecM6c (found: 17/03/2022) and ‘The Strategic Defence and Security Review: Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty’, HM Government, 19/10/2010, https://bit.ly/3JJ7X7B (found: 17/03/2022).

- 2‘National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015’, HM Government, 23/11/2015, https://bit.ly/3JHZ26f (found: 17/03/2022).

- 3See: ‘NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence 2022 Factsheet’, NATO, 02/2022, https://bit.ly/3qAZGeo (found: 17/03/2022) and ‘Boosting NATO’s presence in the east and southeast’, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, 28/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3E0GfjT (found: 17/03/2022); and ‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 16/03/2022) and ‘Defence in a competitive age: Defence Command Paper’, Ministry of Defence, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3LmXM97 (found: 17/03/2022).

- 4‘Integrated Operating Concept’, Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, 2020, https://bit.ly/ioc2025 (found: 17/03/2022).

- 5Ibid.

- 6For more on the concept of seapower states, see: Andrew Lambert, Seapower States: Maritime Culture, Continental Empires, and the Conflict that Made the Modern World (New Haven, Massachusetts: Yale University Press, 2018).

- 7‘Continentalisation’ refers to the process whereby terrestrial powers attempt to close the sea and to incorporate it into their borders. Ibid, p. 320.

- 8.Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History (New York City: Picador, 2012).

- 9Mark Galeotti, ‘The Minsk Accords: Should Britain declare them dead?’, Council on Geostrategy, 24/05/2021, https://bit.ly/3ICl8Wx (found: 24/03/2021).

- 10Ihor Kabanenko, ‘Freedom of Navigation at Stake in Sea of Azov: Security Consequences for Ukraine and Wider Black Sea Region’, The Jamestown Foundation, 06/11/2018, https://bit.ly/35kVMig (found: 28/03/2021).

- 11‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 16/03/2022).

- 12Because Russia’s renewed offensive against Ukraine has undermined commercial activity between the UK and Russia, these calculations and statistics exclude Russia.

- 13These statistics are drawn from the Office for National Statistics. See: ‘UK Trade: January 2022’, Office for National Statistics, 11/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3DeMHnC (found: 17/03/2022).

- 14Kibrom Abay et al., ‘The Russia-Ukraine crisis poses a serious food security threat for Egypt’, International Food Policy Research Institute, 14/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3iFXPR2 (found: 23/03/2022).

- 15These statistics are drawn from the United Nations’ Comtrade Database. See: ‘Comtrade Database’, United Nations, 2022, https://bit.ly/3qGGyvw (found: 24/03/2022).

- 16Ibid and ‘Yemen: Millions at risk as Ukraine war effect rocks region’, World Food Programme, 14/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3wGvfqT (found: 23/03/2022).

- 17For more on the UK’s unique geostrategic position in Europe, see: Nicholas Spykman, America’s Strategy in World Politics (London: Transaction Publishers, 2008 [1942]), p. 98.

- 18‘Military Balance 2022: Further assessments’, International Institute for Strategic Studies, 15/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3uAmg89 (found: 13/03/2022).

- 19See: ‘The UK’s nuclear deterrent: what you need to know’, Defence Nuclear Organisation, 22/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3Npr0Wz (found: 17/03/2022).

- 20See: ‘NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence 2022 Factsheet’, NATO, 02/2022, https://bit.ly/3qAZGeo (found: 17/03/2022) and ‘Boosting NATO’s presence in the east and southeast’, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, 28/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3E0GfjT (found: 17/03/2022).

- 21Julia Voo et al., ‘National Cyber Power Index 2020: Methodology and Analytical Considerations’, Belfer Centre, 09/2020, https://bit.ly/3DcGJn8 (found: 17/03/2022).

- 22‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3vX8RGY (found: 16/03/2022). Emphasis added.

- 23Ibid. The 2015 NSS and SDSR used the term ‘wider state competition’. See: ‘National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015’, HM Government, 23/11/2015, https://bit.ly/3JHZ26f (found: 17/03/2022).

- 24Ibid.

- 25See: Nick Carter, Speech: ‘Dynamic security threats and the British Army’, Ministry of Defence, 23/02/2018, https://bit.ly/3tR5eU9 (found: 17/03/2022).

- 26‘Integrated Operating Concept’, Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, 2020, https://bit.ly/ioc2025 (found: 17/03/2022).

- 27‘Defence in a competitive age: Defence Command Paper’, Ministry of Defence, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3LmXM97 (found: 17/03/2022).

- 28Ibid.

- 29Ibid. This mention of the Black Sea is the only one in the Integrated Review, however.

- 30Ibid.

- 31The Black Sea has seen Royal Navy warships deployed 11 times since 2014: HMS Chiddingford (2014), HMS Duncan (2015, 2017, 2018, and 2019), HMS Daring (2017), HMS Echo (2018-2019), HMS Dragon (2020), HMS Trent (2021) and HMS Defender (2021).

- 32See: Molly McKew, ‘HMS Defender goes for a pleasure cruise through Russian narrative warfare in the Black Sea’, Great Power, 23/06/2021, https://bit.ly/3tKsl2z (found: 13/03/2022).

- 33For a good overview of this agreement, see: Eren Waitzman, ‘UK-Ukraine Credit Support Agreement’, House of Lords Library, 16/12/2021, https://bit.ly/36A6PEH (found: 28/03/2021).

- 34‘Annual Survey of Ukrainian Experts’, Ukrainian PRISM, 24/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3iW753L (found: 17/03/2022).

- 35Poland may not be in the Black Sea region itself, but nevertheless has importance given its positioning between that body of water and the Baltic Sea. Poland has provided the main logistical hub for arms shipments intended to help Ukraine fight Russia. See: ‘United Kingdom, Poland and Ukraine foreign ministers’ joint statement’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 17/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3NnbxpX (found: 17/03/2022).

- 36For more on the Kremlin’s approach, see: James Rogers and Alexander Lanoszka, ‘A ‘Crowe Memorandum’ for the twenty-first century’, Council on Geostrategy, 02/03/2021, https://bit.ly/385eN9q (found: 17/03/2022).

- 37See: Charlie Edwards, ‘Futures thinking (and how to do it…)’, Demos, 2005,https://bit.ly/3iCnLNd (found: 15/03/2022).

- 38Using the following adjectives – extreme, severe, significant, moderate, limited, low or inconsequential – we specify the extent to which these concerns would affect British interests.

- 39Luis Simón and Alexander Lanoszka, ‘The Post-INF European Missile Balance: Thinking About NATO’s Deterrence Strategy’, Texas National Security Review, 3:3 (2020), pp. 12-30.

- 40Jamey Keaten, ‘United Nations says 6.5 million people have been displaced inside Ukraine’, PBS News Hour, 18/03/2022, https://to.pbs.org/3wWmGIP (found: 18/03/2022).

- 41See: Benjamin Tallis, ‘Drop the excuses and embrace Ukraine’, Britain’s World, 22/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3tI9sgI (found: 23/03/2022).

- 42See: Boris Jonhson, ‘Global Britain’, Hansard, 16/06/2020, https://bit.ly/3JLiBdM (found: 25/03/2022).