Foreword

Never before has the relationship between the United Kingdom (UK) and Ukraine been so important. Our two countries, on either side of Europe, are working closely together to ensure that Vladimir Putin fails in his attempt to destroy a democratic European country by force of arms and undermine the security of the whole of Europe.

Our two nations stand united in defence of national sovereignty and the right of all countries to determine their own affairs. The British people stand with the people of Ukraine.

The UK has been by Ukraine’s side throughout this time. Britain acted decisively when Ukraine needed help. It used its intelligence to undermine Russia’s strategic initiative in launching its renewed offensive, just as it provided the Ukrainian Armed Forces with anti-armour weapons to destroy enemy tank columns as they advanced on Kyiv.

We are proud of the enduring Ukrainian-British partnership. Our diplomatic efforts have galvanised allies and partners and isolated Putin’s regime.

Yet, we must think about the future as well as the past. Ukraine must win. It is not enough to ensure that Putin fails. Absent a Ukrainian victory, peace cannot last. Ukraine needs to come out stronger from this war, militarily, politically, and economically, to ensure Russia does not dare to attack it again. Ukraine is grateful to have the UK by its side, determined to facilitate such a strategic outcome.

Britain also wants to lead in supporting the Ukrainian Government’s Reconstruction and Development Plan and will host next year’s Ukraine Recovery Conference.

But we need to do more. This paper, by Alexander Lanoszka, Hanna Shelest and James Rogers, provides options for further deepening the partnership between our two nations. Covering the diplomatic, informational, military and economic dimensions of cooperation, it explains what the British and Ukrainian governments can do now, and in the years ahead, to ensure that we strengthen one another and the open Euro-Atlantic order we both hold dear.

In resisting the actions of the Kremlin and other malign actors attempting to upend global norms and standards, the UK and Ukraine stand united. Under our leadership, as Foreign Secretary and Foreign Minister, both our diplomatic systems – the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine – are working tirelessly to help Ukraine prevail.

– The Rt. Hon. Liz Truss MP

Foreign Secretary of the United Kingdom

– Dmytro Kuleba

Foreign Minister of Ukraine

Executive summary

- Since the United Kingdom (UK) recognised Ukrainian independence in 1992, the bilateral relationship between the two countries has grown ever deeper, particularly since the signing of the Political, Free Trade and Strategic Partnership Agreement (PFTSPA) in 2020.

- This strategic partnership has only deepened with Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine. As intelligence revealed that the Kremlin would renew its offensive, Britain began to provide progressively greater amounts of financial, humanitarian and military support to Ukraine. Decisive action taken by Her Majesty’s (HM) Government in January and February 2022 ensured Ukraine was able to defend Kyiv, and the UK has since continued to lead Europe in supporting Ukraine.

- HM Government is determined to help Ukraine uphold its sovereignty and territorial integrity, protect Ukrainian democracy, and ensure that Russia’s renewed war of aggression fails. British assistance has ensured that the relationship between the two countries is now as close as it has ever been: Ukraine is now one of Britain’s most important partners in Europe, and the UK is one of Ukraine’s.

- Russia’s renewed offensive notwithstanding, the economic relationship between the two countries has also been strengthening since the PFTSPA was signed. Though Ukraine has endured significant damage at the hands of Russia’s military machine, it has great potential as a large market. By retaining at least some access to the Black Sea, Ukraine should remain integrated into the global economy, with the ability to export key products, such as raw materials, and agriculture.

- Against the backdrop of intensifying geopolitical competition – and for Ukraine, outright war – this Policy Paper explores the evolving relationship between the UK and Ukraine. In particular, it explains the importance of the strategic partnership between the two powers, while also identifying options for deepening it even more. In all cases, the ‘DIME’ mode of analysis is adopted, which categorises policy options through Diplomatic, Informational (and cultural), Military, and Economic instruments of national power.

- To deepen relations in the years ahead, the governments of Britain and Ukraine should pursue the following options:

- Diplomatic options:

- Build on the PFTSPA by holding annual Strategic Dialogues, while extending cooperation to biannual 2+2 ministerial meetings, involving the British and Ukrainian foreign and defence secretaries and ministers;

- Move forward with the trilateral agreement between Poland, the UK, and Ukraine, including the establishment of a Track 1.5 process to explore how cooperation might be maximised;

- Support Ukraine’s long-term ambitions in relation to NATO, the EU and the Three Seas Initiative;

- Continue to lead within the G7 on sanctions;

- Lead internationally on issues like justice (in the International Court of Justice), chemical weapons (in the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons) and maritime law;

- Explore multilateral and bilateral options for security guarantees for Ukraine.

- Information options:

- Develop an active and dynamic discursive ‘campaign’ (as envisaged by the UK’s 2020 Integrated Operating Concept) to:

- Push back against anti-Ukrainian, ‘Putinist’ and anti-systemic narratives when articulated by Moscow and/or its proxies and supporters;

- Counter attempts by Russia and other countries to delegitimise or to discount Ukraine’s sovereignty and explain why it is right for Ukrainians to fight to determine their own affairs;

- Re-emphasise the Crimea Platform to pressure Russia and to remind the world that Russia’s annexation of Crimea remains fundamentally illegitimate;

- Continue to present the food crisis and Russia’s deliberate exploitation of it as a violation of human rights to pile on international pressure and allow for different avenues to address it;

- Provide opportunities for Ukrainians to discuss ‘decolonisation’ in terms of the impact of Soviet occupation and Russian imperialism, while emphasising contemporary Russian public attitudes about Ukraine and other countries neighbouring Russia.

- Deepen intelligence cooperation, particularly on releasing intelligence information in a proactive way to deprive Russia and other adversaries of seizing the strategic initiative;

- Promote stronger British-Ukrainian cultural and educational cooperation:

- Establish special programmes for Ukrainian artists and academics, who need to leave Ukraine temporarily;

- Open a representative office of the Ukrainian Institute – Ukraine’s national cultural institute – in London;

- Facilitate cultural exchanges and participation of artists, musicians, researchers, academics in exchange programmes and residencies in both countries. As well as establish student exchange programmes that will allow both sides to raise interests in mutual study.

- Develop an active and dynamic discursive ‘campaign’ (as envisaged by the UK’s 2020 Integrated Operating Concept) to:

- Military options:

- Push forward with training 10,000 Ukrainian troops every 120 days and extend the programme to include NATO allies to increase the number of Ukrainian personnel to be trained;

- Establish an inverted version of Operation ORBITAL;

- Plan for a Royal Navy-led international mission to open maritime communication lines to facilitate Ukrainian exports of agricultural products and undertake de-mining operations in the Black Sea;

- Coordinate international efforts to provide Ukraine with arms over a long period by leading by example in the so-called ‘Ramstein Format’.

- Economic options:

- Join efforts with like-minded allies and partners, particularly the EU, the US, Canada, Norway, Japan and Australia aimed at revitalising Ukraine’s economic fortunes over the long term with a ‘Marshall Plan’ for Ukraine;

- Help Ukraine to rebuild its energy storage facilities and its vast renewable energy potential;

- Provide investment for the speedy recovery Ukraine’s digital and information technology sectors;

- Work with Poland and countries surrounding the Black Sea – particularly Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey – to plan for terrestrial options to facilitate Ukrainian exports given that Russia has blockaded the Ukrainian coast.

1.0 Introduction

That the United Kingdom (UK) and Ukraine would become close strategic partners might have appeared a strange proposition only a few years ago. For some observers, Britain’s recent support for Ukraine – the most extensive of any country other than the United States (US) – has even come as a surprise: arguments have been heard that London was too compromised by corrupt Russian money (so-called ‘Londongrad’), too estranged from European security affairs following its exit from the European Union (EU), too uneven in its historical support for Eastern Europe, and too focused on ‘tilting’ towards the Indo-Pacific, to be a reliable security provider for Ukraine. And yet, the UK has become one of Ukraine’s leading partners. Among others, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, President of Ukraine, was invited to address the House of Commons, and Boris Johnson, British Prime Minister, made two surprise visits to Kyiv in early April and mid-June 2022, respectively.1‘Ukraine: Johnson pledges aid to Zelensky in Kyiv meeting’, British Broadcasting Corporation, 10/04/2022, https://bbc.in/39zpx0G (checked: 14/07/2022). These gestures are the pinnacle of a relationship which has been established for over three decades, particularly after the signing of the Political, Free Trade and Strategic Partnership Agreement (PFTSPA) in October 2020.2‘UK-Ukraine political, free trade and strategic partnership agreement’, Department for International Trade, 09/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3NXzYtW (checked: 14/07/2022).

Though on different sides of Europe, Britain and Ukraine have a direct geostrategic and geoeconomic interest in one another. For years, the kleptocratic regime of Vladimir Putin, deeply fearful of political change in Russia, has sought to extinguish democratic alternatives in surrounding nations, which might act as sources of inspiration for Russian opposition forces. This is why it has targeted Ukraine, Russia’s largest European neighbour. During the 2000s and 2010s, Ukrainians demanded a more democratic future, which the Russian regime saw as the threat to its own interests. This is why the Kremlin, having attempted to weaken Ukraine for years, mounted its so-called ‘special military operation’ – to decapitate the Ukrainian Government – on 24th February 2022. Though Ukraine successfully repelled the initial onslaught against its capital region and thwarted the Kremlin’s plans to take the strategic cities of Mykolayiv and Odesa, Russia has been gaining ground to the east and south of the country. If the Kremlin were to achieve suzerainty over Ukraine, or worse, take control of the entire country, not only would Ukraine cease to exist in a meaningful sense, but Britain’s European geostrategy would be severely compromised – with untold consequences and implications. For the UK, Ukraine is a bulwark against Russia; for Ukraine, Britain is a critical provider of strategic support as it resists attempts to erase it from the map of Europe.

Equally, the two countries are increasingly important economic partners. Though Ukraine has endured significant damage at the hands of Russia’s military machine – over 10% of Ukrainians have been displaced, whole cities and communities have been destroyed, and suffering has been inflicted which will last generations – it remains a large and growing market. By retaining at least some access to the Black Sea, Ukraine assures itself of its long-term place in the global economy and ability to export key products, such as raw materials, and agriculture. Moreover, the rebuilding of the country offers significant opportunities to modernise infrastructure and housing. In this sense, the British-Ukrainian partnership is vital to both sides and has the potential to grow in further significance in the years to come.

With this in mind, the purpose of this Policy Paper is to explore the evolving relationship between the UK and Ukraine, to explain its importance, and to identify options for how to deepen it even more. In all cases, the ‘DIME’ mode of analysis is adopted, which categorises policy options through Diplomatic, Informational (and cultural), Military, and Economic instruments of national power. While diplomatic, military and economic elements are self-explanatory, this Policy Paper embraces an expansive definition of the information dimension to cover the cultural domain as well. Information therefore includes ‘discursive statecraft’ (including combatting disinformation and propaganda campaigns), intelligence cooperation, cyber security, and educational or cultural initiatives.

In terms of structure, this Policy Paper begins by outlining the history of relations between the UK and Ukraine since Ukraine seceded from the Soviet Union in 1991. It then analyses their diplomatic, informational, military and economic relations, as well as how both countries tend to see one another on the international stage. The paper moves on to explain why Britain and Ukraine make for ideal partners, before, finally, outlining how the two powers – one replete with its financial and military wherewithal, the other determined to prevail against a foreign invasion – could work together over the coming months and years to ensure that their shared vision for an open international order is upheld and realised.

2.0 Contemporary history of British-Ukrainian relations

The UK recognised Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union on 31st December 1991 and the two countries established formal diplomatic relations within two weeks (see Appendix 1 for a timeline of subsequent relations). Britain first became involved in Ukrainian security affairs in 1992 when, along with Belarus and Kazakhstan, Ukraine began plans to dismantle the strategic nuclear weapons it had inherited from the Soviet Union. The Budapest Memorandum was drafted partly in response to an urgent request from the Ukrainian Government to the British Embassy for a document to undergird Ukrainian territorial sovereignty in response to calls in 1994 from the then ‘President of Crimea’ – a position abolished by the Ukrainian Parliament in 1995 – for the transfer of Crimea to Russia.3Email correspondence with Raymond Asquith, Counsellor, British Embassy, Kiev (1992-1997) on 16/06/2022. With this document, Britain, Russia, and the US, pledged not to violate Ukraine’s territorial integrity in exchange for Ukraine giving up its remaining Soviet nuclear arms. This agreement also involved assurances to Belarus and Kazakhstan following their own decisions to renounce nuclear weapons.

During the post-Cold War era, most cooperation between the two countries happened through the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), as well as through United Nations (UN) or Group of Seven (G7) initiatives. The UK also lent financial assistance and civil society support to Ukraine as it attempted its fitful transition to democracy and a market-based economy.4World Bank, ‘Ukraine Country Assistance Evaluation’, Report No. 21358, 08/11/2000, https://bit.ly/3OiaqI0 (checked: 14/07/2022), pp. 12-13 and ‘Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between EU and Ukraine’, European Commission, 14/06/1994, https://bit.ly/3aQl61R (checked: 14/07/2022). Following the 2004 Orange Revolution, the UK backed Ukraine’s aspirations to join the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and NATO. The next decade saw some stagnation in bilateral relations, but they picked up after Russia’s occupation of Crimea and destabilisation of the Donbas region in 2014. British and Ukrainian businesses also began enjoying the opportunities provided by the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement of 2014.5‘Association Agreement between the European Union and its Member States, of the one part, and Ukraine, of the other part’, Official Journal of the European Union, 29/05/2014, https://bit.ly/3OdvYVZ (checked: 14/07/2022).

In 2015, Operation ORBITAL (see Box 1) was launched by Sir Michael Fallon, then the British Secretary of State for Defence , to help make the Ukrainian Armed Forces more resilient and to enhance their ability to deter aggression. At the same time, the UK took a leading role in NATO’s Trust Fund on Command, Control, Communications and Computers (C4) (initiated in 2014), assisting Ukraine in modernising its C4 structures and capabilities. These efforts helped Ukraine resist Russia’s initial assault in February 2022.

Box 1: Operation ORBITAL

Operation ORBITAL was launched by Her Majesty’s (HM) Government in early 2015 in response to Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea. Its main purpose was to provide non-lethal military training and support to the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Since it began, the scope of Operation ORBITAL expanded significantly. The initial deployment of 30 British troops focused on providing logistics, medical, and general training to the Ukrainian military. The number of British troops stationed in Ukraine eventually grew to 100. British personnel operated in ‘short term training teams’ on a rotating basis, and collaborated with NATO members in the training.6Ministry of Defence, ‘Operation ORBITAL explained: Training Ukrainian Armed Forces’, Voices of the Armed Forces via Medium, https://bit.ly/3MVoiGJ (checked: 14/07/2022). The operation was suspended in February 2022 shortly before Russia stepped up offensive operations against Ukraine. Operation ORBITAL trained some 22,000 Ukrainian personnel.7See: ‘PM considers a major military offer to NATO’, Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, 30/01/2022, https://bit.ly/3NRguY9 (checked: 14/07/2022) and Dan Sabbagh and Clea Skopeliti, ‘UK troops sent to help train Ukrainian army to leave country’, The Guardian, 12/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3tSXalb (checked: 14/07/2022).

2.1 How both nations view one another in their national strategies

The growing closeness of the relationship between Britain and Ukraine is apparent in how the two countries have ‘framed’ one another in recent years, not least in a number of strategic reviews. Even if the two countries see one another differently, this framing does not appear to be intentional and strategic – as a form of ‘discursive statecraft’ (see Box 2).8For more on discursive statecraft and national positioning strategies, see: James Rogers, ‘Discursive statecraft: Preparing for national positioning operations’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3tA3cHm (checked: 14/07/2022). Rather, it appears to reflect changing assumptions about where the other fits in relation to Europe and the wider world, as well as the relative importance of the bilateral relationship between the UK and Ukraine.

Box 2: ‘Discursive Statecraft’

‘Discursive statecraft’ accounts for attempts by governments to articulate concepts, ideas, and objects into new discourses in order to degrade existing political and ideological frameworks or generate entirely new ones. It could be likened to offensive soft power.

In the final instance, such efforts are designed to (re-)structure how people can think and act, as well as what can be said and thought. This can involve the projection of vast new ideological or geostrategic formations, such as ‘democratic liberalism’, ‘Soviet communism’, ‘the West’, the ‘non-aligned’, and ‘the Third World’, as seen during the Cold War, or the recent emergence of the ‘free and open’ Indo-Pacific. But it can also involve positioning operations to alter and to restructure another country’s understanding of its place in the world, and encourage its leaders (and other nations) to accept new narratives about the target.

2.1.1 How Ukraine sees the UK

In 2020-2021, Ukraine adopted a number of strategic documents that define its foreign and security policy vision. In all of them, the UK was framed as a major power with which collaboration is essential to achieve its national security objectives. The UK receives two mentions in the 2020 National Security Strategy of Ukraine and seven mentions in the 2021 Foreign Policy Strategy of Ukraine.9See: ‘Стратегія національної безпеки України’ [‘National Security Strategy of Ukraine’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 14/09/2020, https://bit.ly/3zTeXwD (checked: 14/07/2022) and ‘Стратегія зовнішньої політики України’ [‘Strategy of Ukraine’s foreign policy’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 26/08/2021, https://bit.ly/3zz4vdm (checked: 14/07/2022).

- National Security Strategy of Ukraine (2020): In this document, which lays out Ukraine’s national security priorities and the direction policy must take to achieve them, ‘developing relations’ with the UK is seen as vital in ‘counter[ing] common challenges and threats’ to Ukraine.10‘Стратегія національної безпеки України’ [‘National Security Strategy of Ukraine’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 14/09/2020, https://bit.ly/3zTeXwD (checked: 14/07/2022), Article 6. The Ukrainian Government also sees ‘comprehensive cooperation’ with the UK as a ‘strategic priority for Ukraine [that] is aimed at strengthening guarantees of independence and sovereignty, promoting democratic progress and [the] development of Ukraine.’11Ibid., Article 35.

- Foreign Policy Strategy of Ukraine (2021): As Ukraine’s first foreign policy strategy, this document defines the country’s priorities and mechanisms, and identifies relations with individual states and regions.12‘Стратегія зовнішньої політики України’ [‘Strategy of Ukraine’s foreign policy’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 26/08/2021, https://bit.ly/3zz4vdm (checked: 14/07/2022). Article 99 reconfirms the ‘strategic character’ of relations with the UK, as outlined in the 2020 National Security Strategy.13Ibid., Article 99. Articles 109 and 110 further outline Ukraine’s strategic vision for relations with the UK: Britain is labelled an ‘influential state outside the EU’ and a ‘strategic partner that plays an important role in the formation and preservation of international solidarity in support of the state sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine’.14Ibid., Articles 109 and 110. The PFTSPA between Ukraine and the UK is cited as the document that will guide the future development of the bilateral relationship.15‘UK-Ukraine political, free trade and strategic partnership agreement’, Department for International Trade, 09/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3NXzYtW (checked: 14/07/2022).

2.1.2 How the UK sees Ukraine

While Ukraine has come to see the UK as a major power, Britain continues to frame Ukraine as a European country in need of strategic support. In the 2015 National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review, Ukraine was mentioned 13 times, though largely in the context of Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014 and British attempts to shore up security in the Euro-Atlantic region. The strategy did, however, state that HM Government would ‘continue to work to uphold Ukraine’s sovereignty, assist its people and build resilience.’16‘National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015’, Cabinet Office, 23/11/2015, https://bit.ly/3xwWumq (checked: 14/07/2022). This framing was largely unchanged in the 2021 Integrated Review on defence, security, development and foreign policy, which was described, on announcement, as the ‘deepest review’ of Britain’s strategic posture since the end of the Cold War.17‘Boris Johnson Pledges Security, Defence And Foreign Policy Review’, Forces Network, 01/12/2019, https://bit.ly/39w2QdN (checked: 14/07/2022). This review resulted in two strategies:

- Global Britain in a competitive age (2021): In this document, which approximates a ‘grand strategy’ for the UK, Ukraine is mentioned only twice, again more as an object in a wider geopolitical theatre.18‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/37DZx3n (checked: 14/07/2022). HM Government commits itself to ‘support others in the Eastern European neighbourhood and beyond to build their resilience to state threats. This includes Ukraine, where we will continue to build the capacity of its armed forces.’19Ibid. Furthering the work of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine is also mentioned.20Ibid.

- Defence in a competitive age (2021): This document, which provides the military dimension of British grand strategy, mentions Ukraine three times. First, Ukraine is framed primarily as a country which ‘has suffered significant territorial loss as a result of Russian aggression’.21‘Defence in a competitive age: Defence Command Paper’, Ministry of Defence, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3Ho0MBi (checked: 14/07/2022). Second, the UK pledges to ‘help to build Ukraine’s resilience to the continued aggressive tactics – conventional and sub-threshold – used by its neighbour. Our capacity building mission, which includes both land and maritime training, will support the development of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and their interoperability with NATO’. Third, Ukraine is identified as a ‘partner’, albeit indirectly as part of a ‘campaign’ to build ‘capacity’ and ‘resilience’ among the Ukrainian Armed Forces.22Ibid.

2.2 The emergence of a strategic partnership

Prior to 2016, the UK was firmly part of the EU and gave strong support to Ukraine’s EU and NATO aspirations; both countries saw one another largely, though not exclusively, through an EU and NATO prism. Under these circumstances, Britain and Ukraine saw little need for a deeper bilateral relationship. The British withdrawal from the EU, however, provided an incentive for the two countries to forge a more resolute and bilaterally-focused relationship across the diplomatic, informational, military and economic spheres. Moreover, the two countries began to share a common interest in that they had both been on the receiving end of Russia’s aggression.23Beyond the poisonings of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in March 2018, the Kremlin has also targeted the UK with ‘discursive statecraft’. See: Andrew Foxall, ‘How Russia “positions” the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3Hq0A4s (checked: 14/07/2022). The first changes were evident after the Kerch Bridge incident in November 2018, after which the UK increased its support for the development of the Ukrainian Navy.24Claire Mills, ‘Military Assistance to Ukraine 2014-2021’, House of Commons Library, 04/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3Qmac4g (checked: 14/07/2022), p. 3. These were followed by a raft of assistance measures designed to help modernise the Ukrainian State and make it more effective, inclusive, and transparent, as well as enhanced support for the Ukrainian military.25‘UK programme assistance to Ukraine in 2019-2020’, British Embassy Kyiv, 13/09/2019, https://bit.ly/3OaJmtS (checked: 14/07/2022).

But it was the signing of the PFTSPA in October 2020, which provided the framework for deeper and more structured bilateral cooperation.26‘UK-Ukraine political, free trade and strategic partnership agreement’, Department for International Trade, 09/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3NXzYtW (checked: 14/07/2022). Whereas Britain’s post-Brexit deals with Moldova and Georgia were almost identical to their EU Association Agreements, the PFTSPA with Ukraine is almost 600 pages long, implying that Britain and Ukraine intend to take their political and economic cooperation to a higher level and broader plane. Indeed, although the agreement’s free trade component was developed to reflect British needs and Ukrainian capabilities, especially in agriculture, the main objective of the PFTSPA was to establish a strategic partnership between the two nations. The key aims of this partnership were defined as: developing political and economic cooperation based on common values; promoting, preserving, and strengthening peace; countering Russian aggression; supporting Ukrainian reforms and pace towards EU and NATO membership; cooperating on the international stage; and enhancing collaboration in the fields of justice and law enforcement, as well as cultural exchange.27Ibid.

2.2.1 Diplomatic relations

In December 2021, Britain and Ukraine, following on from the PFTSPA, held their first ‘Strategic Dialogue’ meeting at the senior ministerial level. This resulted in a ‘Joint Communique’ where the two countries declared their commitment to one another:

The UK reaffirms our unwavering commitment to Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and support for Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic path. Ukraine reaffirms, with UK support, its commitment to implementing comprehensive internal reforms, which will build resilience, attract foreign investment and strengthen prosperity.28‘UK-Ukraine joint communique’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3Qnejx1 (checked: 14/07/2022).

Two months later, a new ‘trilateral grouping’ – consisting of Poland, the UK and Ukraine – was announced by Dmytro Kuleba, the Ukrainian Foreign Minister, and Liz Truss, the British Foreign Secretary. This was in line not only with Ukraine’s preference for ‘small alliances’, but also the UK’s growing interest in ‘plurilateralism’ along the so-called eastern and northern ‘flanks’ of Europe.29James Rogers, ‘A new European triumvirate: Plurilateralism in action’, Britain’s World, 02/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3tC5VQD (checked: 14/07/2022). Though the three countries’ foreign ministers met in Kyiv to announce the initiative on 17th February 2022, the accompanying memorandum was not taken forward due to Russia’s renewed assault on Ukraine only a week later.30‘Joint statement by the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland and Secretary of State of the United Kingdom’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, 17/02/2022, https://bit.ly/39XJezE (checked: 14/07/2022). The three sides expected to boost economic, technological and energy cooperation, alongside security coordination.

In keeping with the trajectory of their strategic partnership, vigorously promoted in each country by their respective ambassadors, Melinda Simmons and Vadym Prystaiko, Britain has stood by Ukraine throughout Russia’s aggression. By 1st July 2022, HM Government had provided Ukraine with approximately US$6.25 billion of bilateral financial, military and humanitarian support, more than any country other than the US.31‘Ukraine Support Tracker’, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, 07/07/2022, https://bit.ly/3Oi6tmE (checked: 14/07/2022). This support has been underpinned by significant cross-party cooperation in the Houses of Parliament and the personal support of Johnson, Truss, and Ben Wallace, the Secretary of State for Defence. Zelenskyy was invited to address the House of Commons on 9th March 2022, while Johnson’s visit to Kyiv on 9th April 2022 – the first of a leader from a major power – boosted trust between the two countries, so much so that Zelenskyy described the UK as his ‘great ally’ and the UK and Ukraine as ‘brothers and sisters’.32See: ‘Speaker Hoyle invites “courageous” Ukrainian President to give Commons address’, UK Parliament, 09/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3yjSCab (checked: 14/07/2022); Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Interview: ‘Volodymyr Zelenskyy in conversation with Roula Khalaf’, Financial Times, 07/06/2022, https://on.ft.com/3tD8XDZ (checked: 14/07/2022); and ‘“We’re lucky UK is our friend” says Ukrainian MP after Boris Johnson addresses Kyiv parliament’, ITV, 03/05/2022, https://bit.ly/3NwkhJp (checked: 14/07/2022). The British prime minister followed up with a subsequent visit to the Ukrainian capital on 17th June 2022, making him the only foreign leader, alongside Andrzej Duda, President of Poland, to have visited more than once since Russia’s renewed assault began.33Boris Johnson, Speech: ‘Prime Minister’s remarks at a press conference in Kyiv: 17 June 2022’, Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, https://bit.ly/3xZF8im (checked: 14/07/2022).

2.2.2 Informational activities

The UK, alongside the US, was the first large nation to signal that it was paying serious attention to the possibility of a renewed Russian attack on Ukraine. It was also the first to actively release intelligence during December 2021 and January 2022 in an attempt to undermine the Kremlin’s invasion plans.34Dan Sabbagh, ‘Ukraine crisis brings British intelligence out of the shadows’, The Guardian, 18/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3xOlTIL (checked: 14/07/2022).

In contrast to working together to thwart Russia’s ambitions, cultural and educational activities have never been a priority between the two countries. This oversight was not helped by the fact that the Ukrainian diaspora in the UK had not been particularly visible before 2014, perhaps owing to its relatively small size. This diaspora is represented by two major diaspora waves that are not always interconnected: the ‘old’ wave of post-Second World War immigrants and ‘new’ immigrants from independent Ukraine.35‘Population of the UK by country of birth and nationality’, Office for National Statistics, 25/09/2021, https://bit.ly/3Nn2u79 (checked: 14/07/2022). Both waves have strongly assimilated with British society, but they became more active in terms of promoting Ukraine, its interests and culture after 2014 due to Russian aggression.

To mark 30 years of diplomatic relations, however, 2022 was expected to be a year of Ukrainian culture in Britain, and British culture in Ukraine, but Russia’s aggression stalled these plans. Nevertheless, adaptations were made and the British Council and Ukrainian Institute launched the UK/Ukraine ‘season’ on 24th June 2022, with more in-person events taking place in Britain and greater online access, as well as a shift in focus to the ‘changing needs and priorities of the Ukrainian cultural sector.’36‘UK/Ukraine season: About’, British Council and Ukrainian Institute, undated, https://bit.ly/3u49e2W (checked: 14/07/2022). Significant opportunity exists for building greater cultural awareness between the two countries and enhancing the perception of one another, particularly on the British side (see Box 3).

Box 3: British perceptions of Ukraine

Research conducted by the Ukrainian Institute in Autumn 2021 demonstrated a low level of awareness among Britons about Ukrainian culture, as well as a tendency to mix it with Russian and Soviet cultures.37Sergiy Gerasymchuk and Hanna Shelest, ‘Perception of Ukraine and Ukrainian culture abroad. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’, Ukrainian Institute, 22/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3O9AKEz (checked: 14/07/2022). This research also found that Russian narratives have had a major impact, especially on British public perceptions on historical events such as World War II, Holodomor, Crimea annexation, etc. At the same time, this lack of knowledge opens up perspectives for promoting and exploring Ukrainian phenomena and modern culture in Britain.

The British elite remained open towards Russia until 2022, irrespective of whether those surveyed supported the Conservative or Labour parties, considered themselves part of the upper class, or were engaged in cultural activities.38‘Johnson on first Moscow visit by UK top diplomat in 5 years?’, Associated Press, 22/12/2017, https://bit.ly/3QytG5Q (checked: 14/07/2022). Russophilia among Britons does not, however, necessarily translate into support for the Kremlin; Britons tend to be highly critical of the Russian State and its policies. Instead, Russophilia primarily manifests itself as admiration of Russia as a country, the Russian people, their history, and culture.

2.2.3 Military cooperation

Despite increased dialogue, even on defence and security, the UK continued to display caution in terms of supplying Ukraine with advanced weapons. Britain preferred to provide Ukraine with training assistance through Operation ORBITAL, which was complemented by the establishment of a Maritime Training Initiative in December 2020 to bolster the Ukrainian Navy.39‘UK launches multinational training to enhance Ukrainian Navy against threats from the East’, Ministry of Defence, 18/08/2020, https://bit.ly/3mMn4TQ (checked: 14/07/2022). As British intelligence started to gather evidence during July 2021 that Russia was planning a renewed offensive against Ukraine, the UK stepped up Operational ORBITAL and began to signal its intention to supply the Ukrainian Armed Forces with advanced weapons. With the signing of a Memorandum of Implementation between the British and Ukrainian ministries of defence and Babcock, an instrument was established for the delivery of Brimstone anti-ship missiles, two Sandown class minehunter vessels, and eight guided-missile craft to the Ukrainian Navy, the construction of two new naval bases, and the training of additional Ukrainian naval personnel.40‘Parliament ratified Ukrainian-British agreement on development of Ukrainian Navy capabilities’, Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, 27/01/2022, https://bit.ly/3QkIapV (checked: 14/07/2022).

Further, as Russia’s bellicose intentions became increasingly apparent, the UK was the first, starting in January 2022, to supply Ukraine with large volumes of anti-armour weapons. Wallace authorised the transfer by airlift of over 2,000 Next-generation Light Anti-tank Weapons (NLAW)41‘Statement by the Defence Secretary in the House of Commons, 17 January 2022’, Ministry of Defence, 17/01/2022, https://bit.ly/3xTUINy (checked: 14/07/2022) and ‘Defence Secretary statement to the House of Commons on Ukraine: 9 March 2022’, Ministry of Defence, 09/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3MXGUpI (checked: 14/07/2022). – armaments which were important in helping Ukraine resist Russia’s subsequent assault, particularly on the Kyiv region. Since then, the UK has supplied Ukraine with an additional 3,000 NLAW and 1,500 other anti-tank weapons, as well as Starstreak anti-air missile batteries, Harpoon anti-ship missiles, heavy artillery, multiple-launch rocket systems, and armoured vehicles – with even more pledged.42‘Praise for Ukraine support as Defence industry offers more help’, Ministry of Defence, 20/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3byyuIc (checked: 14/07/2022). Most recently, in June 2022, the UK announced its intention to train 10,000 Ukrainians every 120 days for service in the Ukrainian Army.43‘UK to offer major training programme for Ukrainian forces as Prime Minister hails their victorious determination’, Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, 17/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3xWoQa6 (checked: 14/07/2022). At the same time, the UK has helped its smaller allies and partners get military equipment to Ukraine, just as it has sent Challenger II battle tanks to Poland to ‘backfill’ to enable the Polish Government to transfer its own tanks – similar to those used by the Ukrainian Army – to Ukraine.44‘Defence Secretary statement to the House of Commons on Ukraine: 25 April 2022’, Ministry of Defence, 25/04/2022, https://bit.ly/3A7QrYt (checked: 14/07/2022).

2.2.4 Economic interaction

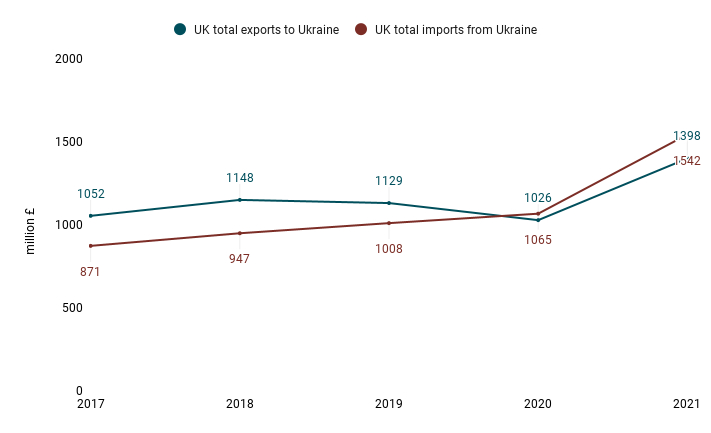

For the past 20 years, bilateral trade between the UK and Ukraine has been on an upward trajectory. This was hardly affected by Covid-19, and British-Ukrainian trade experienced a significant increase after the PFTSPA. Indeed, British exports to Ukraine rose by 36%, and Ukrainian exports to the UK by 45%, between 2020 and 2021 (see Graph 1). Moreover, the UK is one of the few countries which has almost parity in Ukrainian trade in goods and services. Although Britain has never been one of Ukraine’s leading 10 trade partners for goods, it ranked fourth in 2021 in terms of services.45‘Annual volume of Ukraine’s foreign trade of services with countries of the world (by the type of service)’, State Statistics Service of Ukraine, 01/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3u403Q3 (checked: 14/07/2022). Since October 2020, when Baroness Meyer was appointed by the British prime minister to enhance trade between the two nations, Britain has had a Trade Envoy to Ukraine – representing HM Government’s belief in the potential of the relationship.46‘Prime Minister’s Trade Envoys’, HM Government, undated, https://bit.ly/3z2bkU7 (checked: 14/07/2022).

According to 2021 data, the biggest export categories from Ukraine to the UK were ferrous metals (26.6% of total), fats and oils of animal or vegetable origin (16.6%), oil seeds (15.1%), grains (13.4%), and electrical machinery (7.5%).47‘Foreign trade in certain types of goods by country in 2021’, State Statistics Service of Ukraine, 24/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3u403Q3 (checked: 14/07/2022). Britain exported land transport, except railway (22.6% of total), nuclear reactors and machinery (15.3%), chemical products (8%), mineral fuels, oil and products of its distillation (8%), alcohol (6.6%) to Ukraine.48Ibid. The UK imported virtually no oil-seeds and oleaginous fruits from Ukraine until 2019, and vegetable oil and fats imports have increased by approximately 263% over the past five years, underscoring Ukraine’s increasingly important role in providing these products.49‘Trade in goods: country-by-commodity imports historical data 1997 to 2017’, Office for National Statistics, 11/11/2021, https://bit.ly/3tRidEM (checked: 14/07/2022) and ‘Trade in goods: country-by-commodity imports’, Office for National Statistics, 13/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3QUR8dU (checked: 14/07/2022). Indeed, due to Russia’s renewed offensive, British supermarkets are currently rationing some cooking oils to limit customer stockpiling, and prices of the product have increased by 10%-20%.50Zoe Wood, ‘Tesco to ration cooking oil purchases as war in Ukraine hikes food prices’, The Guardian, 22/04/2022, https://bit.ly/3yaUZfy (checked: 14/07/2022).

Graph 1: Trade in goods and services between the UK and Ukraine

In terms of services, 2021 statistics show that Ukraine exported telecommunications and information technology (62% of total), transport services (19.1%), and business services (13.6%).52‘Annual volume of Ukraine’s foreign trade of services with countries of the world (by the type of service)’, State Statistics Service of Ukraine, 01/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3u403Q3 (checked: 14/07/2022). The UK exported business services (27.2%), financial activities (15%), travel services (14.7%), and royalty and other services connected with intellectual property rights (14.6%).53Ibid.

3.0 Why Britain and Ukraine should deepen relations

As a result of Russia’s renewed military thrust into Ukraine, the relationship between the UK and Ukraine has deepened substantially. There is no reason why it cannot – or indeed, should not – deepen further still, particularly given the interests that the two countries increasingly share in common. Although Britain and Ukraine sit at the opposite ends of Europe, have different levels of economic development, and different perceptions of the utility of the EU, the two countries share – as Box 4 shows – a number of national interests, even if their degree of prioritisation is not entirely the same.

Box 4: Shared national interests according to the two countries’ security strategies

Britain’s national interests:

- Sovereignty: the ability of the British people to elect their political representatives democratically in line with their constitutional traditions, and to do so free from coercion and manipulation.

- Security: the protection of our people, territory, CNI [Critical National Infrastructure], democratic institutions and way of life.

- Prosperity: the ability of the British people to enjoy a high level of economic and social well-being, supporting their families and seizing opportunities to improve their lives.54‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/37DZx3n (checked: 14/07/2022).

Ukraine’s national interests:

- Defending independence and state sovereignty;

- Restoration of territorial integrity within the internationally recognised state border of Ukraine;

- Social development, first of all development of human capital;

- Protection of the rights, freedoms and legitimate interests of the citizens of Ukraine;

- European and Euro-Atlantic integration.55‘Стратегія національної безпеки України’ [‘National Security Strategy of Ukraine’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 14/09/2020, https://bit.ly/3zTeXwD (checked: 14/07/2022), Article 5.

For starters, both countries see Russia as, in Britain’s case, an ‘acute’ and ‘direct threat’, or in Ukraine’s case, as an ‘aggressor state’, to their own security, as well as the broader geopolitical order in the Euro-Atlantic area.56‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security,Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/37DZx3n(checked: 14/07/2022) and ‘Стратегія національної безпеки України’ [‘National Security Strategy of Ukraine’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 14/09/2020, https://bit.ly/3zTeXwD (checked: 14/07/2022), Article 39. Both are committed to upholding their own sovereignty, including protecting their national institutions and democracies, right to determine their own affairs, and way of life. Both are committed to maintaining an open international order, particularly in Europe and its neighbouring regions and seas. Britain, an insular state on an archipelago with two territories in other parts of Europe, and Ukraine, a large country to the north of the Black Sea, both have interests in preventing the ‘continentalisation’ of the sea.57‘Continentalisation’ refers to the process whereby terrestrial powers attempt to close the sea and to incorporate it into their borders. See: Andrew Lambert, Seapower States: Maritime Culture, Continental Empires, and the Conflict that Made the Modern World (New Haven, Massachusetts: Yale University Press, 2018), p. 320. Indeed, given their dependence on maritime communication lines, both pay homage to open seas and freedom of navigation.58Ibid. and Ibid., Article 17. And both countries are also aware of the strategic significance of NATO and the EU, even if the UK is a member only of NATO, while Ukraine seeks accession to both organisations – an objective of which it has enshrined in its constitution in 2019.59‘Конституція України’ [‘Constitution of Ukraine’], Законодавство України [Legislation of Ukraine], 1996 with amendments of 2019, https://bit.ly/3xUDUq2 (checked: 14/07/2022).

Moreover, the UK and Ukraine are ideally suited to work together due to their complementary capabilities. Both are also populous – the UK’s population is 68 million, while Ukraine’s is 42 million – with large markets. Economically, Ukraine has a growing service sector, particularly in terms of its role as a digital hub for information technology and software development. And, militarily, the UK has a strong navy, while the Ukrainian Armed Forces are ever-more battle-hardened, having fought for years against a ruthless nuclear power bent on territorial conquest.

Looking forward, the UK and Ukraine make for ideal strategic partners. Ukraine has become a central node in Britain’s newfound vision for Europe, which stretches from ‘the northern’ to the ‘southern flanks of Europe’, where HM Government intends to ‘support collective security from the Black Sea to the High North, in the Baltics, the Balkans and the Mediterranean.’60‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/37DZx3n (checked: 14/07/2022). Given Russia’s expansionist intent, Ukraine, though not a NATO ally, has become the central defensive bulwark of the Euro-Atlantic area insofar as it has been condemned to absorb the Kremlin’s aggressive lunges.61Alexander Lanoszka and James Rogers, ‘Why Britain should continue to support Ukraine’, Britain’s World, 16/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3xOLGR5 (checked: 14/07/2022). Meanwhile, for Ukraine, the UK – independent of Russia for energy and all the baggage it entails – makes for an ideal European partner: British economic, military and intelligence wherewithal has proven invaluable in helping Ukraine enhance its resilience and resist Russian aggression. Both countries are also critical to one another in their efforts to broaden multilateral cooperation in Europe: the trilateral group formed in February 2022 with Poland has much potential to expand in scope and function.

3.1 Strategic policy options

Irrespective of Russia’s ongoing offensive, the UK and Ukraine have a number of options across the diplomatic, informational, military and economic domains where they can deepen their strategic partnership:

- Diplomatic options: Close and personal diplomatic coordination between the UK and Ukraine has been invaluable to deepening the strategic partnership between the two countries. British diplomatic support for Ukraine has been significant in the face of Russia’s aggression, just as Ukraine’s support for the UK has helped the country recover its reputation as a major Euro-Atlantic power after leaving the EU. Moving forward, the two countries should:

- Build on the PFTSPA by holding annual Strategic Dialogues, while extending cooperation to biannual 2+2 ministerial meetings, involving the British and Ukrainian foreign and defence secretaries and ministers;

- Move forward with the trilateral agreement between Poland, the UK, and Ukraine, including the establishment of a Track 1.5 process to deepen links between the diplomatic, political and expert communities in the three countries and to explore how cooperation might be maximised;

- Support Ukraine’s long-term ambitions in relation to NATO, the EU and the Three Seas Initiative, not least by working with like-minded allies and partners such as Poland, Romania, the Baltic and Nordic states, Canada and the US. Whatever Ukraine’s prospects for joining NATO, Kyiv will search for closer cooperation in different spheres and possible establishment of multilateral (especially trilateral) formats which involve the UK;

- Continue to lead within the G7 on sanctions. Of course the EU and the US are the big players, but the UK can do a lot of thought leadership on sanctions options, and sometimes lead by example (e.g., as on oil);

- Lead internationally on issues like justice (in the International Court of Justice), chemical weapons (in the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons) and maritime law. As a permanent member of the UN Security Council, the UK should also amplify its ‘discursive statecraft’ on Russian behaviour and do more to shape global opinions;

- Explore multilateral and bilateral options for security guarantees for Ukraine (see Box 5), particularly with the US, Canada, Poland, Turkey, Romania and the Baltic and Nordic states. To be credible, any guarantee would need to significantly enhance Ukraine’s ability to deter a future Russian assault once a cease fire or peace treaty has been agreed. Such agreements should also not limit Ukrainian options for search of additional security arrangements, including NATO membership.

Box 5: Security Guarantees

A state might issue a security guarantee to another state in the event that its interests directly align. A security guarantee can take a number of forms:

- A multilateral military alliance, such as the Western Union Defence Organisation (1948) or NATO (1949). With this form of guarantee one or more major powers pledges to defend, through a legally-binding treaty, a number of allies in the event that one or more of them comes under foreign attack.

- A bilateral military alliance, such as the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 or the Treaty of Dunkirk (1947). With this kind of guarantee, a great power proclaims, through a legally-binding instrument, that it will come to the aid of its ally in the event that it comes under attack from a foreign power (often under specific conditions).

- A formal consultative assurance, such as the Five Power Defence Arrangement (1971) between the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia and Singapore. With this form of guarantee, the parties agree to consult with one another if certain conditions are met – e.g., if an aggressor attacks a certain ally or if an attack takes place in a specific geographic area.

- An informal security assurance, similarly to those issued to Finland and Sweden by the UK in May 2022. With this kind of guarantee, a major power agrees – albeit not through a legally binding instrument – to come to the aid of a smaller state if it is attacked by an aggressor.

All four of these guarantees could involve either structured cooperation to assist an ally enhance its armed forces to improve national defence and resilience, or the forward deployment of a major power’s armed forces to a vulnerable ally’s national homeland to deny it to a foreign aggressor. Although a formal treaty demonstrates strategic intent, structured attempts to enhance a vulnerable ally or partner’s security or the forward-positioning of forces in sufficient numbers to its territory can have an equal, if not even greater impact on deterring an adversary.

At the very least, Ukraine would not be satisfied with a new version of the Budapest Memorandum, which was predicated on pledges and consultative assurances that were never honoured. Indeed, Ukraine would be dissatisfied just with consultative guarantees as this mechanism already exists within the Ukraine-NATO Distinctive Partnership Charter.

- Information options: Irrespective of Russia’s renewed assault on Ukraine, both countries have a broader interest in countering and pushing back against the Kremlin’s wider offensive against the Euro-Atlantic order of which its attempt to deny Ukraine sovereignty is a key part. Meanwhile, although cultural and educational exchange might be difficult for Ukraine at the moment, the two countries continue to share interests in boosting their awareness of one another. Moving forward, the two countries would do well to:

- Develop an active and dynamic discursive ‘campaign’ (as envisaged by the UK’s 2020 Integrated Operating Concept)62The Integrated Operating Concept explains ‘campaigning’ in the following way: ‘We need to create multiple dilemmas that unhinge a rival’s understanding, decision-making and execution. This requires a different way of thinking that shifts our behaviour, processes and structures to become more dynamic and pre-emptive, information-led and selectively ambiguous. In essence, a mindset and posture of continuous campaigning in which all activity, including training and exercising, will have an operational end.’ to:

- Push back against anti-Ukrainian, ‘Putinist’ and anti-systemic narratives when articulated by Moscow and/or its proxies and supporters. This should develop an integrated vision for what a free and open international order in the Euro-Atlantic stands for – political, economic and cultural freedom for citizens, geopolitical openness, including freedom of navigation – and why it is superior to the visions of authoritarian rivals;

- Counter attempts by Russia and other countries to delegitimise or to discount Ukraine’s sovereignty and explain why it is right for Ukrainians to fight to determine their own affairs;63The British Foreign Secretary and Ukrainian Foreign Minister have already partnered to project such narratives. See: Liz Truss and Dmytro Kuleba, ‘We must ignore the defeatist voices who propose to sell out Ukraine’, Daily Telegraph, 25/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3ONOqFa (checked: 14/07/2022).

- Re-emphasise the Crimea Platform to pressure Russia and to remind the world that Russia’s annexation of Crimea remains fundamentally illegitimate;

- Continue to present the food crisis and Russia’s deliberate exploitation of it as a violation of human rights to pile on international pressure and allow for different avenues to address it;

- Provide opportunities for Ukrainians to discuss ‘decolonisation’ in terms of the impact of Soviet occupation and Russian imperialism, while emphasising contemporary Russian public attitudes about Ukraine and other countries neighbouring Russia.

- Deepen intelligence cooperation, particularly on releasing intelligence information in a proactive way to deprive Russia and other adversaries of seizing the strategic initiative; Ukraine’s status as a NATO Enhanced Opportunity Partner provides a formal framework for this;

- Promote stronger British-Ukrainian cultural and educational cooperation, particularly as Ukraine has captured the public imagination within the UK, and vice versa:

- Establish special programmes for Ukrainian artists and academics, who need to leave Ukraine temporarily, which may trigger longer-term cultural exchange;

- Open a representative office of the Ukrainian Institute – Ukraine’s national cultural institute – in London;

- Facilitate cultural exchanges and participation of artists, musicians, researchers, academics in exchange programmes and residencies in both countries. As well as establish student exchange programmes that will allow both sides to raise interests in mutual study.

- Develop an active and dynamic discursive ‘campaign’ (as envisaged by the UK’s 2020 Integrated Operating Concept)62The Integrated Operating Concept explains ‘campaigning’ in the following way: ‘We need to create multiple dilemmas that unhinge a rival’s understanding, decision-making and execution. This requires a different way of thinking that shifts our behaviour, processes and structures to become more dynamic and pre-emptive, information-led and selectively ambiguous. In essence, a mindset and posture of continuous campaigning in which all activity, including training and exercising, will have an operational end.’ to:

- Military options: The initial packages of British military aid were important in helping Ukraine resist the Kremlin’s original strategic objectives, namely seizing Kyiv and decapitating the Ukrainian Government. Now Ukraine needs a continuous flow of advanced weapons, in significant quantities, or else it will lose further ground to Russia. Indeed, the Kremlin is almost certainly counting on free and open countries, such as the UK, to grow increasingly fatigued by the conflict, to the extent that deliveries of weapons dry up. More importantly, every day where Ukraine lacks the means to fight, more Ukrainian soldiers and civilians die unnecessarily. Under these circumstances, the two countries ought to:

- Push forward with training 10,000 Ukrainian troops every 120 days and extend the programme to include NATO allies to increase the number of Ukrainian personnel to be trained;

- Establish an inverted version of Operation ORBITAL: the Ukrainian military has already gained much experience in fighting an interstate war against a large and ruthless adversary. Ukrainian personnel have much to teach British Army officers (and their NATO counterparts) about techniques, tactics, and procedures in fighting a great power adversary on land and with air defence. This could be implemented by establishing a joint UK-Ukraine Centre of Excellence on Contemporary Warfare;

- Plan for a Royal Navy-led international mission to open maritime communication lines to facilitate Ukrainian exports of agricultural products and undertake de-mining operations in the Black Sea;

- Coordinate international efforts to provide Ukraine with arms over a long period by leading by example in the so-called ‘Ramstein Format’ – monthly donors’ conferences for Ukraine’s partners to coordinate their efforts to provision the Ukrainian Armed Forces with the equipment they need to resist Russia. Indeed, the UK ought to prepare itself to act as an ‘arsenal’ for Ukraine, with all the financial obligations and defence-industrial requirements this might entail.

- Economic options: Irrespective of the future, the Ukrainian economy has been crippled by Russia’s renewed offensive, to the extent that it must contend with destroyed infrastructure, property damage, and disinvestment. Ukraine’s main post-war task will be to rebuild its critical national infrastructure, which has already started in the liberated territories. An unreconstructed and impoverished Ukraine would create further instability in the Black Sea region, with long-term humanitarian and political implications for neighbouring countries. With this in mind, the two countries should:

- Join efforts with like-minded allies and partners, particularly the EU, the US, Canada, Norway, Japan and Australia aimed at revitalising Ukraine’s economic fortunes over the long term with a ‘Marshall Plan’ for Ukraine. This programme may involve repairing and developing Ukrainian transportation and logistics infrastructure as well as boosting its information and telecommunications industries;

- Help Ukraine to rebuild its energy storage facilities and its vast renewable energy potential, which could not only generate much-needed revenue for reconstruction but also help the EU to diversify away from Russia and towards a more reliable and trustworthy supplier;64For more on how Ukraine could assist Europe in terms of energy security, see: Alexander Lanoszka, James Rogers and Patrick Triglavcanin, ‘A new energy policy for Europe: The significance of Ukraine’, Council on Geostrategy, 08/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3NaeuZC (checked: 14/07/2022).

- Provide investment for the speedy recovery Ukraine’s digital and information technology sectors;

- Work with Poland and countries surrounding the Black Sea – particularly Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey – to plan for terrestrial options to facilitate Ukrainian exports given that Russia has blockaded the Ukrainian coast.

4.0 Conclusion

Irrespective of Russia’s ambitions, the partnership between Britain and Ukraine should be deepened. But the scale of Russia’s ongoing offensive means that the relationship needs also to be responsive to changing circumstances. After all, the extent to which Ukraine can stop Russia’s ‘special military operation’ and return, if not to the situation prior to February 2014, then certainly to 24th February 2022, will shape the future of the strategic partnership between Kyiv and London. If Ukraine prevails in reversing Russia’s renewed onslaught, it will recover and make for a stronger strategic partner for the UK. If Russia seizes control of the Donbas and other territories, Ukraine will be permanently threatened, demanding prolonged British support. And if Russia pushes into Odesa, Ukraine will be crippled and the strategic environment in Europe might quickly deteriorate even more, risking further miscalculation on the part of the Kremlin – even systemic war. Undoubtedly, Ukrainians have demonstrated extraordinary resolve and heroism in resisting Russia’s ‘special military operation’, but it is unclear what Ukraine will look like in the future unless the Ukrainian Government receives greater international assistance.65‘Thirteen All-Ukrainian Sociological Survey: Foreign Policy Orientations’, Rating Group Ukraine, 20/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3HXE6be (checked: 14/07/2022).

HM Government’s Integrated Review pledges that the UK will remain the ‘leading European Ally within NATO’ by 2030.66‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/37DZx3n (checked: 14/07/2022). If Britain is to realise this strategic objective, it would do well to do everything in its power to ensure that Ukraine prevails over Russia’s aggression. It is important to remember that the Kremlin’s strategic objectives – with Peter the Great’s conquests as their point of reference – do not stop at Ukraine’s borders; if Russia prevails there, the Russian leadership, looking to uphold its power, will almost certainly look to its next target, feeling bolder and less constrained than ever.67Speaking on 10th June 2022 in Moscow, Putin explained: ‘Apparently, it is also our lot to return [what is Russia’s] and strengthen [the country]. And if we proceed from the fact that these basic values form the basis of our existence, we will certainly succeed in solving the tasks that we face.’ See: Andrew Roth, ‘Putin compares himself to Peter the Great in quest to take back Russian lands’, The Guardian, 10/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3I50IXy (checked: 14/07/2022). British diplomatic leadership, informational coordination, military transfer and economic assistance, can help Ukraine stop and reverse Russia’s advance. The Ukrainian people – over 90% according to opinion polls – are prepared to fight to prevail.68‘Thirteen All-Ukrainian Sociological Survey: Foreign Policy Orientations’, Rating Group Ukraine, 20/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3HXE6be (checked: 14/07/2022). If HM Government provides Ukraine with progressively greater support, an increasingly robust relationship will be formed with the British people, which will not only help the two countries navigate a more competitive era, but will also open opportunities for deepened trade and cultural exchange.

Appendix 1

Timeline of British-Ukrainian relations since Ukraine’s independence

| January 1992 | Formal diplomatic relations established |

| February 1993 | Leonid Kravchuk, President of Ukraine, visits the UK |

| December 1994 | The UK signs the Budapest Memorandum with the US and Russia pledging not to violate Ukraine’s sovereignty |

| December 1995 | Leonid Kuchma, President of Ukraine, visits the UK |

| April 1996 | John Major, British Prime Minister, visits Ukraine |

| October 2005 | Viktor Yuschenko, President of Ukraine, visits the UK |

| May 2008 | Joint Statement by Viktor Yuschenko and Gordon Brown that officially declared the strategic nature of Ukrainian-British relations |

| 2008-2009 | Viktor Yuschenko, President of Ukraine, visits the UK three times |

| February 2015 | Operation ORBITAL launched by the UK |

| April 2017 | Petro Poroshenko, President of Ukraine, visits the UK |

| August 2020 | UK-led Maritime Training Initiative launched to train the Ukrainian Navy |

| October 2020 | Volodymyr Zelenskyy, President of Ukraine, visits the UK |

| October 2020 | UK-Ukraine PFTSPA signed |

| April 2021 | HMS Defender upholds Ukrainian sovereignty near Crimea |

| June 2021 | Memorandum of Implementation signed to push Ukrainian naval capabilities enhancement projects forward. Projects include: Delivery of new naval platforms and defensive shipborne armaments; Training of Ukrainian Navy personnel; Creation of new naval bases; Transfer of two Sandown class minehunter vessels. |

| December 2021 | First UK-Ukraine Strategic Dialogue under the PFTSPA held |

| January 2022 | Britain begins supplying Ukraine with NLAWs |

| April 2022 | Boris Johnson, British Prime Minister, visits Kyiv |

| June 2022 | The UK agrees, alongside the US and Germany, to provide Ukraine with heavy artillery |

| June 2022 | Boris Johnson, British Prime Minister, visits Kyiv |

| June 2022 | Britain agrees to train 10,000 Ukrainian forces every 120 days |

About the authors

Dr Alexander Lanoszka is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Waterloo, Canada and an Ernest Bevin Associate Fellow in Euro-Atlantic Geopolitics at the Council on Geostrategy. He has previously taught at City, University of London, and was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Dickey Centre for International Understanding at Dartmouth College, and a Stanton Nuclear Security Postdoctoral Fellow at Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Security Studies Programme. Dr Lanoszka has worked for the United States Department of Defence and has consulted for Global Affairs Canada. He holds a PhD in Philosophy and an MA in Politics, both from Princeton University.

James Rogers is Co-founder and Director of Research at the Council on Geostrategy, where he specialises in the connections between Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific geopolitics and British strategic policy. Previously, he held positions at the Henry Jackson Society, the Baltic Defence College, and the European Union Institute for Security Studies. He has been invited to give oral evidence at the Foreign Affairs, Defence, and International Development committees in the House of Commons. He holds an MPhil in Contemporary European Studies from the University of Cambridge and an award-winning BSc Econ (Hons) in International Politics and Strategic Studies from the University of Wales, Aberystwyth.

Dr Hanna Shelest is the Director of Security Programmes at the Foreign Policy Council ‘Ukrainian Prism’ and Editor-in-chief at UA: Ukraine Analytica. Before this, she had served for more than ten years as a Senior Researcher at the National Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of Ukraine, Odesa Branch. In 2014, Dr Shelest was a Visiting Research Fellow at the NATO Defense College in Rome. Since 2006, she has been a guest lecturer for the Diplomatic Academy of Ukraine, George C. Marshall European Centre for Security Studies, Swedish Defence University, National Defence College of the United Arab Emirates, NATO Defence College, World Economic Forum, and Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The Council on Geostrategy would like to express appreciation to Ferrexpo PLC for sponsoring the publication of this Policy Paper.

Equally, the authors would like to thank Patrick Triglavcanin, Research Assistant at the Council on Geostrategy, for his support in drafting this Policy Paper. In addition, they would like to thank the officials and experts who attended the research workshop held on 16th June 2022 to consider the ideas contained in this Policy Paper.

Disclaimer

This publication should not be considered in any way to constitute advice. It is for knowledge and educational purposes only. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Council on Geostrategy or the views of its Advisory Council. Any conclusions drawn from data included in this publication are the responsibility of the author and not that of the issuing body.

No. SBIPP08 | ISBN: 978-1-914441-25-7

- 1‘Ukraine: Johnson pledges aid to Zelensky in Kyiv meeting’, British Broadcasting Corporation, 10/04/2022, https://bbc.in/39zpx0G (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 2‘UK-Ukraine political, free trade and strategic partnership agreement’, Department for International Trade, 09/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3NXzYtW (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 3Email correspondence with Raymond Asquith, Counsellor, British Embassy, Kiev (1992-1997) on 16/06/2022.

- 4World Bank, ‘Ukraine Country Assistance Evaluation’, Report No. 21358, 08/11/2000, https://bit.ly/3OiaqI0 (checked: 14/07/2022), pp. 12-13 and ‘Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between EU and Ukraine’, European Commission, 14/06/1994, https://bit.ly/3aQl61R (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 5‘Association Agreement between the European Union and its Member States, of the one part, and Ukraine, of the other part’, Official Journal of the European Union, 29/05/2014, https://bit.ly/3OdvYVZ (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 6Ministry of Defence, ‘Operation ORBITAL explained: Training Ukrainian Armed Forces’, Voices of the Armed Forces via Medium, https://bit.ly/3MVoiGJ (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 7See: ‘PM considers a major military offer to NATO’, Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, 30/01/2022, https://bit.ly/3NRguY9 (checked: 14/07/2022) and Dan Sabbagh and Clea Skopeliti, ‘UK troops sent to help train Ukrainian army to leave country’, The Guardian, 12/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3tSXalb (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 8For more on discursive statecraft and national positioning strategies, see: James Rogers, ‘Discursive statecraft: Preparing for national positioning operations’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3tA3cHm (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 9See: ‘Стратегія національної безпеки України’ [‘National Security Strategy of Ukraine’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 14/09/2020, https://bit.ly/3zTeXwD (checked: 14/07/2022) and ‘Стратегія зовнішньої політики України’ [‘Strategy of Ukraine’s foreign policy’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 26/08/2021, https://bit.ly/3zz4vdm (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 10‘Стратегія національної безпеки України’ [‘National Security Strategy of Ukraine’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 14/09/2020, https://bit.ly/3zTeXwD (checked: 14/07/2022), Article 6.

- 11Ibid., Article 35.

- 12‘Стратегія зовнішньої політики України’ [‘Strategy of Ukraine’s foreign policy’], Ради національної безпеки і оборони України [National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine], 26/08/2021, https://bit.ly/3zz4vdm (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 13Ibid., Article 99.

- 14Ibid., Articles 109 and 110.

- 15‘UK-Ukraine political, free trade and strategic partnership agreement’, Department for International Trade, 09/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3NXzYtW (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 16‘National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015’, Cabinet Office, 23/11/2015, https://bit.ly/3xwWumq (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 17‘Boris Johnson Pledges Security, Defence And Foreign Policy Review’, Forces Network, 01/12/2019, https://bit.ly/39w2QdN (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 18‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, Cabinet Office, 07/03/2021, https://bit.ly/37DZx3n (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 19Ibid.

- 20Ibid.

- 21‘Defence in a competitive age: Defence Command Paper’, Ministry of Defence, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3Ho0MBi (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 22Ibid.

- 23Beyond the poisonings of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in March 2018, the Kremlin has also targeted the UK with ‘discursive statecraft’. See: Andrew Foxall, ‘How Russia “positions” the United Kingdom’, Council on Geostrategy, 07/04/2021, https://bit.ly/3Hq0A4s (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 24Claire Mills, ‘Military Assistance to Ukraine 2014-2021’, House of Commons Library, 04/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3Qmac4g (checked: 14/07/2022), p. 3.

- 25‘UK programme assistance to Ukraine in 2019-2020’, British Embassy Kyiv, 13/09/2019, https://bit.ly/3OaJmtS (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 26‘UK-Ukraine political, free trade and strategic partnership agreement’, Department for International Trade, 09/11/2020, https://bit.ly/3NXzYtW (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 27Ibid.

- 28‘UK-Ukraine joint communique’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3Qnejx1 (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 29James Rogers, ‘A new European triumvirate: Plurilateralism in action’, Britain’s World, 02/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3tC5VQD (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 30‘Joint statement by the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland and Secretary of State of the United Kingdom’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, 17/02/2022, https://bit.ly/39XJezE (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 31‘Ukraine Support Tracker’, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, 07/07/2022, https://bit.ly/3Oi6tmE (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 32See: ‘Speaker Hoyle invites “courageous” Ukrainian President to give Commons address’, UK Parliament, 09/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3yjSCab (checked: 14/07/2022); Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Interview: ‘Volodymyr Zelenskyy in conversation with Roula Khalaf’, Financial Times, 07/06/2022, https://on.ft.com/3tD8XDZ (checked: 14/07/2022); and ‘“We’re lucky UK is our friend” says Ukrainian MP after Boris Johnson addresses Kyiv parliament’, ITV, 03/05/2022, https://bit.ly/3NwkhJp (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 33Boris Johnson, Speech: ‘Prime Minister’s remarks at a press conference in Kyiv: 17 June 2022’, Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, https://bit.ly/3xZF8im (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 34Dan Sabbagh, ‘Ukraine crisis brings British intelligence out of the shadows’, The Guardian, 18/02/2022, https://bit.ly/3xOlTIL (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 35‘Population of the UK by country of birth and nationality’, Office for National Statistics, 25/09/2021, https://bit.ly/3Nn2u79 (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 36‘UK/Ukraine season: About’, British Council and Ukrainian Institute, undated, https://bit.ly/3u49e2W (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 37Sergiy Gerasymchuk and Hanna Shelest, ‘Perception of Ukraine and Ukrainian culture abroad. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’, Ukrainian Institute, 22/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3O9AKEz (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 38‘Johnson on first Moscow visit by UK top diplomat in 5 years?’, Associated Press, 22/12/2017, https://bit.ly/3QytG5Q (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 39‘UK launches multinational training to enhance Ukrainian Navy against threats from the East’, Ministry of Defence, 18/08/2020, https://bit.ly/3mMn4TQ (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 40‘Parliament ratified Ukrainian-British agreement on development of Ukrainian Navy capabilities’, Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, 27/01/2022, https://bit.ly/3QkIapV (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 41‘Statement by the Defence Secretary in the House of Commons, 17 January 2022’, Ministry of Defence, 17/01/2022, https://bit.ly/3xTUINy (checked: 14/07/2022) and ‘Defence Secretary statement to the House of Commons on Ukraine: 9 March 2022’, Ministry of Defence, 09/03/2022, https://bit.ly/3MXGUpI (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 42‘Praise for Ukraine support as Defence industry offers more help’, Ministry of Defence, 20/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3byyuIc (checked: 14/07/2022).

- 43‘UK to offer major training programme for Ukrainian forces as Prime Minister hails their victorious determination’, Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, 17/06/2022, https://bit.ly/3xWoQa6 (checked: 14/07/2022).