For the foreseeable future, the United Kingdom (UK) looks set to be the most purposeful European diplomatic and security actor in Eastern Europe. Over the past five years, Britain has ‘tilted’ towards the region with a range of military deployments and practical demonstrations of its commitment to address threats and challenges.

Central to the UK’s Eastern European tilt is Russia, to which London has a distinctive policy to those of Europe’s two other large European states, France and Germany. With major elections in prospect in both and the likely changes of leadership to not profoundly alter their current stances on Russia, the UK’s contribution to Eastern Europe’s security looks set to remain the most purposeful of Europe’s large states. And with the European Union (EU) struggling to forge a collective voice on Russia, the UK’s guarantor role in Eastern Europe may grow further still.

Importantly, Britain’s position corresponds with the Russia element of the new administration of Joe Biden in the United States (US). Unlike France and Germany, the US approach appears to be focused on re-establishing ‘stability’ in the US-Russia relationship rather than a transformational warming. This emerging UK and US correspondence of approaches contrasts with the French-German position which seeks ‘normalisation’ with the current regime in Russia.

Britain’s European presence and action

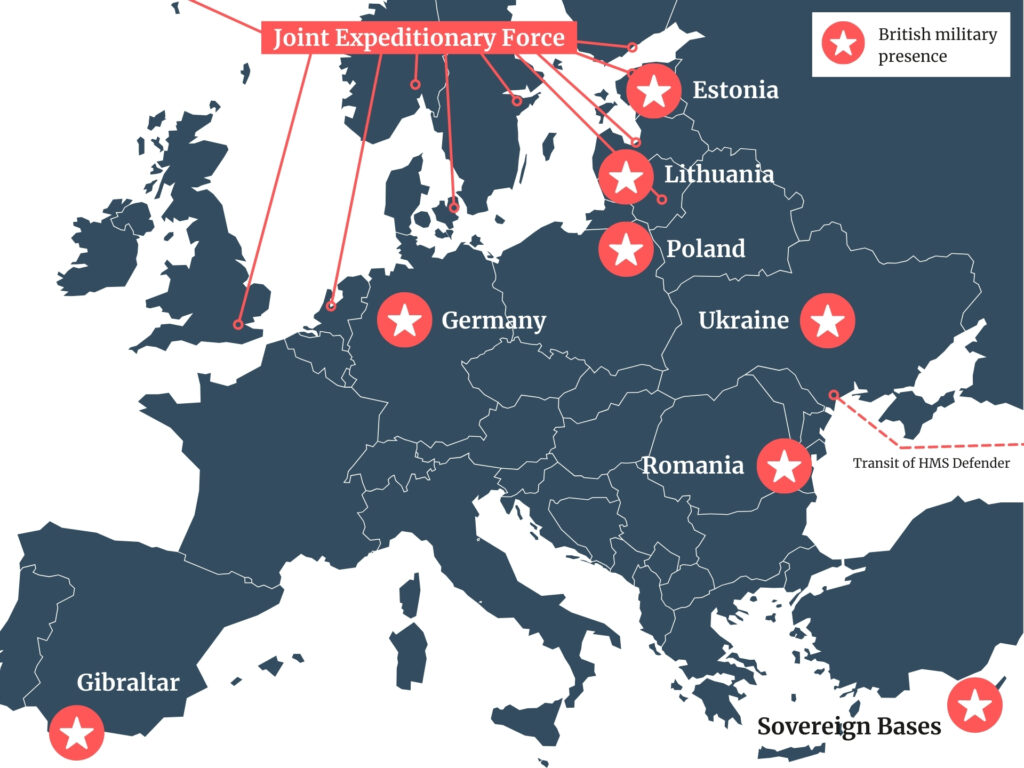

Today, the British strategic presence in Eastern Europe is broader than ever. Not only does the UK provide more troops to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO) Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP) than any other ally (including the US), but it is also present through the EFP in more allies than any other ally. As the framework nation in Estonia, Britain provides approximately 800 troops, while it contributes an additional 150 troops in support of the US (as framework nation) in Poland. At the same time, the UK has provided a persistent presence within NATO’s Baltic Air Policing mission operating Royal Air Force (RAF) Typhoon interceptors out of Armari Air Station in Estonia and Siauliai Air Station in Lithuania. In 2018, Britain also decided to partly reverse the closure – announced in 2010 – of its military and logistical facilities in Germany in the event that its presence further east requires reinforcement.

As it has bolstered the Baltic, the UK has also led the way in the Black Sea. Through Operation ORBITAL, Britain has provided Ukraine with military trainers, over £1.25 billion in loans to finance the reconstruction of the Ukrainian Navy’s shore facilities, and a new generation of fast missile craft. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy has upheld a persistent presence in the Black Sea, most recently manifested by HMS Trent and HMS Defender. As it travelled between Ukraine and Georgia, the latter vessel, a potent Type 45 class air defence destroyer, steamed through the territorial waters of Russian-occupied Crimea on 23rd June, demonstrating that the UK is willing to negate Russia’s territorial claims, unlike other large European powers.

Map: The UK’s geostrategic footprint in Eastern Europe

The UK has also demonstrated considerable leadership in Northern European security with its role in creating and developing the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF). The 10 nation JEF includes NATO and non-NATO states and focuses on developing interoperability between its participants to contribute to the security of the Baltic, ‘Wider North’ and North Atlantic. The JEF is a good example of where the UK is contributing to building new capability for European security by being willing to look beyond institutional theology to add value.

Confusion in other major European capitals

The UK’s presence and action in Eastern Europe is driven by the assumption that Vladimir Putin’s self-serving kleptocracy is – in the words of the Integrated Review – ‘a direct acute threat’ to European security. Consequently, there is a marked difference of analysis and action on Russia emerging between Europe’s major powers: insofar as Russia is a danger, Britain favours the Kremlin’s exclusion from European security, while France and Germany prefer dialogue in an attempt to draw it in.

The British position on Russia therefore contrasts markedly with the approach of the French and German governments. Both Emmanuel Macron, President of France, and Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany, have placed stress on a softer approach towards Russia and held out the prospect of a broad ‘dialogue’ despite the Kremlin’s ongoing occupation of Ukraine and other efforts to undermine European security. Last month’s French-German attempt at the EU’s European Council to bounce other EU members into a summit with Putin demonstrated a concerning lack of regard for maintaining a unified European approach on Russia. It also had the effect of dramatically illustrating the lack of a collective EU policy towards the Kremlin, not least because Poland, the Netherlands and the Baltic states were especially strong in their opposition to the French and German initiative.

Despite the best efforts of Josep Borrell, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, to square a profound difference of opinion on Russia with a new approach predicated on ‘push back’, ‘constrain’ and ‘engage’, the lack of trust between the EU’s ‘Russia realists’ and ‘Russia normalisers’ is as wide as ever. Any evidence of EU push back or constraint of Russia is minimal. France and Germany would simply block it.

Moreover, the EU’s approach towards Russia looks unlikely to evolve substantially without a major shift of position on the part of its two largest states. Unfortunately, Merkel’s departure as chancellor and the upcoming Federal Elections in Germany will not herald a major shift in the direction of Russia policy. Armin Laschet, the Christian Democrats’ contender for the chancellory has stressed the need for more dialogue with the Kremlin, just as he has asserted that NordStream II will be an ‘additional good part of the energy supply’ – despite the fact that Eastern and Central European countries have expressed their contempt for the project.

For his part, Macron has continued with his approach of maintaining a direct bilateral ‘strategic dialogue’ with Putin over recent years. Although the French president’s prospects of re-election in the April 2022 French Presidential Elections are uncertain, he was considered to have the toughest position on Russia of France’s candidates contesting the presidency in 2017. Consequently, Putin may have little to fear from the outcome of France’s 2022 election as a preference for embedding Russia in Europe’s security architecture remains a predominant view among the French strategic elite.

France and Germany’s positions have coalesced on the fantasy that relations with the Kremlin can be ‘normalised’. This position seems to be at odds with that of the current US administration which, as the Biden-Putin Summit in Geneva demonstrated, is to contest and contain Russia, directly challenging egregious behaviour while cooperating on issues (such as nuclear arms control) that contribute to strategic stability.

There is a significant chance that the vaunted EU-US high level dialogue on Russia agreed at the joint summit in June with the ambition to coordinate policy and actions will struggle to deliver substantive outcomes. The Biden administration’s disillusion with French-German positions on Russia could soon be apparent.

Britain: leader of the ‘Russia realists’

With France and Germany leading a rearguard action to establish a caucus of ‘Russia normalisers’, dividing the EU, the UK is the only major European power to offer a realistic approach that is supported by the countries closest to Russia. Unlike Berlin and Paris, London sees Russia’s kleptocracy as a challenger to the European security order and one that needs to be countered. The UK clarity of analysis and action provides a model for like-minded European states, particularly in Eastern Europe, to follow.

To no small extent, the direction of US policy will determine which of these approaches prevails. The big question, at least in the medium to longer term, is whether the US will try to have its own dialogue with the Kremlin in an attempt to constrain the People’s Republic of China (PRC). And if so, the question then becomes: will the US accept tradeoffs in Eastern Europe in exchange for Russian support over the PRC?

Time will tell. What is known is that, today, French and German policy on Russia is unrealistic, the EU is divided, and US thinking is evolving. In this dynamic geopolitical environment, the Baltic states, Poland, Romania and Ukraine, as well as others, would do well to coordinate their policies more directly with London. And the UK ought to prepare to ‘tilt’ further towards the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea region, as well as towards the Baltic, as the new pivot point of European security. Keeping Russia out and preventing other large European countries from inviting Russia in is the key to European peace in the twenty-first century.

Prof. Richard Whitman is Professor of Politics and International Relations at the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent. James Rogers is Director of Research at the Council on Geostrategy.

Join our mailing list!

Stay informed about the latest articles from Britain’s World