Foreword

In the last year, geopolitics and energy policy have become interlinked as never before. Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine has forced Europe to tear itself away from cheap Russian gas and accelerate investment in renewable energy. At the same time, the Chinese Communist Party is seeking to establish a stranglehold over the supply of products the world will need to reach net zero, from electric car batteries to solar panels.

Yet this convergence between environmental, foreign, and domestic policy will pale in comparison to what is to come as climate change worsens. No transnational threat is as global in nature as climate change and biodiversity loss, and the impact of these challenges in each country or region will inevitably affect the prosperity and security of others around the world.

More frequent, more extreme weather events, natural disasters, and the degradation of the environment will drive poverty and instability in countries around the world. Many of the small island nations most at risk from rising sea levels are our friends in the Commonwealth, from Jamaica to Singapore.

The poverty and instability that climate change provokes in developing countries will further mass migration into Europe and to the shores of the English Channel, exacerbating our existing difficulties in stopping illegal crossings. The impact of climate change on migration into the United Kingdom (UK) has already begun, with social unrest in Syria, exacerbated by droughts, helping to start the civil war in that country.

To support our longstanding allies in the Commonwealth and to reduce mass migration into our country, Britain needs to build resilience to climate change, both at home and abroad. That is why I welcome this report from the Council on Geostrategy, which sets out practical actions that His Majesty’s Government can take to achieve this.

Domestically, we need to develop a greater understanding of migrant flows into the UK, the extent to which they are driven by climate change, and how this compares to other European countries. Internationally, we need to step up our climate adaptation efforts and work with other developed countries in the Commonwealth to help more vulnerable member states prepare for the worst.

This report sets out some fresh ideas to tackle these intensifying challenges and will be important reading for political parties and policymakers.

– The Rt. Hon. The Lord Hague of Richmond

Foreign Secretary (2010-2014) and Leader of the Conservative Party (1997-2001)

Executive summary

- The issue of ‘climate migration’ has risen up the agenda. However, it remains poorly understood and ill-defined. Common references of the scale of climate-linked migration are often of worst case scenario projections that do not include cross-border migration.

- Nevertheless, the planet is warming, which will bring more frequent, more extreme weather events. Problems will arise for His Majesty’s (HM) Government and it must prepare. The Policy Paper proposes a distinction between ‘climate-linked’ and ‘climate-provoked’ migration. The former meaning climate change is just one of several factors that encourages the movement of people, while the latter is where climate change is the dominant factor.

- The issues of adaptation and climate-linked or -provoked migration are directly linked to the debate around loss and damage at the United Nations, which are proving slow and combative. HM Government should explore other routes for more direct cooperation with the United Kingdom’s (UK) closest friends through the Commonwealth to speed up adaptation financing, especially for Commonwealth small island developing states (SIDS), but also other climate vulnerable states.

- In the refresh of the Integrated Review, special consideration should be given to improving the resilience of vulnerable states to improve their ability to withstand migratory pressures. A particular focus should be on equipping vulnerable states to deal with natural disasters and shock migration.

- HM Government should seek to boost the Commonwealth’s capacity to build resilience overseas through adaptation. It should also propose the creation of a forum to prepare for the regrettable but increasingly likely eventuality that orderly resettlement from some Commonwealth nations may be necessary to avert humanitarian disaster.

- The Cabinet Office should report annually on migration flows abroad and to the UK. This report would build public confidence in Britain’s immigration system and help to improve transparency. It would likewise help to identify the primary factors driving migration abroad, climate-linked or otherwise, and help HM Government better understand the interplay between climate change, migration, and state-based systemic competition.

1.0 Introduction

‘Climate migration’ has crept into national and international debate. Dramatic projections of millions of people – at times even billions – displaced by climate change have found fertile ground in the popular imagination, especially of those already sensitised to the threat of climate catastrophe and uncontrolled migration.1‘Over one billion people at threat of being displaced by 2050 due to environmental change, conflict and civil unrest’, Institute for Economics and Peace, 09/09/2020, http://bit.ly/3TnAELj (checked: 23/01/2023). For example, alongside fireworks in the colours of the Ukrainian flag, London’s 2023 New Year Fireworks display proudly announced that the capital ‘stands with all those around the world displaced by conflict, strife and the climate crisis’, as though the three automatically go together.2‘Happy New Year Live! London Fireworks 2023 BBC’, BBC via Youtube, 01/01/2023, http://bit.ly/3CiIK25 (checked: 23/01/2023). Meanwhile, journalists and commentators rarely reference the high-end projections of research on the issue, such as the World Bank’s ‘Groundswell’ reports, in their appropriate context, creating a politically compelling but potentially false narrative, which risks overreaction from politicians and policymakers.

The risk here is that popular emotion and media speculation in the world’s most powerful countries, such as the United Kingdom (UK), provokes governments into disproportionate responses, or even costly overreaction. More concerningly, it could encourage vulnerable people in developing countries to move – at significant cost – when they do not need to.3Jan Selby and Gabrielle Daoust, ‘Rapid evidence assessment on the impacts of climate change on migration patterns’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/07/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ep40oj (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 40. Open-ended, poorly thought through or drafted positions on the subject could also be exploited by unscrupulous actors, be they people traffickers or hostile authoritarian states. Attempting to legislate and develop policy through the lens of ‘climate migration’ is therefore challenging and possibly even counterproductive. Although the subject of climate ‘linked’, ‘induced’ or ‘related’ migration is significant,4In this Policy Paper, the phenomenon will be described as ‘climate-linked migration’. it will probably remain inadequately defined and quantified over the next decade.5‘Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities’, Government Office for Science, 20/10/2011, http://bit.ly/3G8MZjp (checked: 23/01/2023). There is no clear definition of a ‘climate migrant’, though the UN’s first Special Rapporteur on Human rights and Climate Change, appointed in March 2022, plans to examine this, see: Michelle Langrand, ‘UN climate expert: I want to find the wormhole between human rights and climate change’, Geneva Solutions, 24/06/2022, http://bit.ly/3Tu2Pba (checked: 23/01/2023). For the most part, the primary drivers of internal displacement and cross border migration will remain poor governance (especially inadequate preparedness for natural disasters), local conflict, competition over scarce resources, and weak economic growth. While these (particularly the latter) may be accentuated by climate change, direct attribution of climate change to migration flows will remain contentious.

That said, it is clear that climate change will shape the activities of people living in the most exposed regions of the world, such as small insular states in the Indo-Pacific and the Caribbean, and arid states in the Levant and North Africa, even if in ways that will be difficult to track. It is therefore sensible to prepare for a future in which migration – climate-linked or otherwise – becomes an enduring feature of both developed and developing countries. In line with the Integrated Review,6The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3v8NUtr (checked: 23/01/2023). which is currently being ‘refreshed’, and the recent speech by James Cleverly, the Foreign Secretary, on future opportunities for British foreign policy,7‘British foreign policy and diplomacy: Foreign Secretary’s speech’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 12/12/2022, https://bit.ly/3PIEcrh (checked: 23/01/2023). the broad answer to this issue is to build resilience, not least in those Commonwealth nations most at risk from climate change. The UK’s ambition should be to prevent ‘shock’ migration and enhance foreign countries’ preparedness in the event of climate-related natural disasters.

With these assumptions in mind, this Policy Paper examines how analysis of climate related migration has been formulated as well as the debates that are founded on and fed into this research. It then examines the primary issues of climate change’s implications for ‘climate-linked’ and ‘climate-provoked’ migration, and how it may affect British interests. Any position taken by His Majesty’s (HM) Government should take into account both the moral duty to protect human life and the need to maintain a secure British border, the foundation of national sovereignty. Consequently, this Policy Paper concludes with a series of recommendations around three themes: building resilience at home, enhancing resilience overseas, and challenging divisive narratives.

2.0 The state of the debate: Claims and credibility

The spectre of migration caused by climate change is a powerful one; it is not uncommon to to see stories referencing a ‘great upheaval’ in the headlines.8Gaia Vince, ‘The century of climate migration: why we need to plan for the great upheaval’, The Guardian, 18/09/2022, http://bit.ly/3Gptx2b (checked: 23/01/2023). ‘Climate migration’ is always a prominent feature of catastrophic narratives. At a more technical level, the issue has crept up the political and strategic agendas: in 2020, the United Nations (UN) High Commission for Refugees published a Strategic Framework for Climate Action; in 2021, the White House published its report on the Impact of Climate Change on Migration; and in 2022, the UN appointed its first Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Climate Change, building on the prior work of the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, a position which lasted from 2015 to 2018.

The extent to which climate change will drive migration remains, however, unclear. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) acknowledges that there are a wide range of estimates for climate induced migration by 2050, ranging from 25 million to one billion.9‘Outlook on Migration, Environment and Climate Change’, International Organisation for Migration, 19/11/2014, https://bit.ly/3WEcxdl (checked: 23/01/2023). The most frequently referenced analysis is the World Bank’s ‘Groundswell Report’ which was published in two parts, in 2018 and 2021, respectively.10‘Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration’, World Bank, 19/03/2018, http://bit.ly/3E7l6FY (checked: 23/01/2023) and ‘Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration’, World Bank, 13/09/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ek7M15 (checked: 23/01/2023). The 2018 headline findings were that 143 million people could be displaced within their countries by 2050 due to climate change. In the latter report, which had greater geographic scope, the forecast was 216 million.11Ibid.

To put these numbers into perspective, over the thirty year period analysed (2020-2050), this amounts to approximately 7.2 million people annually. New internal displacements in 2020 alone were 40.5 million according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), or 48 million according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.12See: ‘Global Report on Internal Displacement 2021’, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 20/05/2021, http://bit.ly/3NWlSdc (checked: 23/01/2023) and ‘Global Trends Report 2021’, United Nations High Commission for Refugees, 01/07/2022, http://bit.ly/3Ey7QeZ (checked: 23/01/2023). International migration in 2020 was 281 million according to the IOM.13‘World Migration Report 2022’, International Organisation for Migration, 01/12/2021, http://bit.ly/3G97lJs (checked: 23/01/2023). 7.2 million people per year, at approximately 17% of current displacements, is significant, but existing displacement patterns clearly pose a greater challenge.

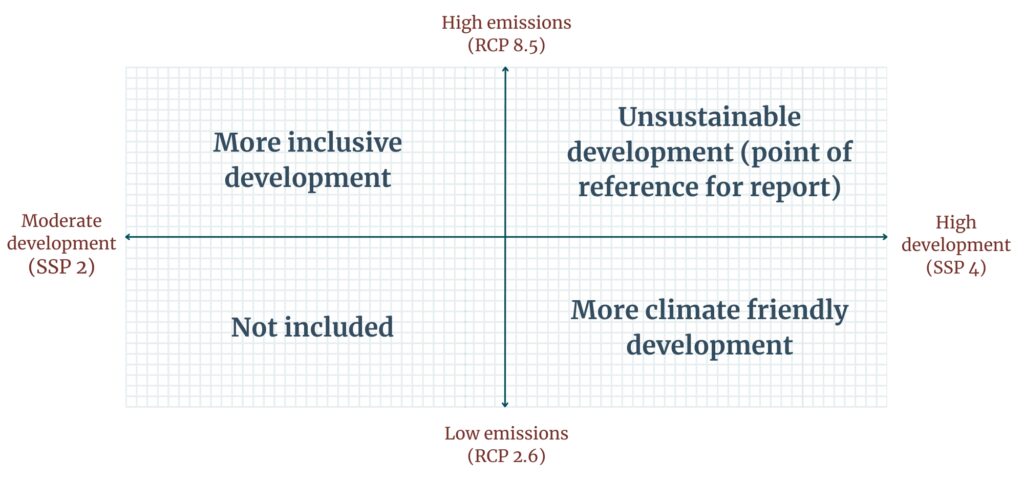

The Groundswell reports are intended to inform worst case planning. As such, they focus on three scenarios, with combinations of population growth, economic projections, and emission pathways. The second report’s headline number of 216 million combines the worst of these – a population growth pathway with high levels of inequality (SSP4) combined with a high emissions pathway (RCP 8.5) – and derives displacement numbers compared to a world with no climate impact.14‘Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration’, World Bank, 13/09/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ek7M15 (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 320.

Analytically this structure may make sense, but two oversights undermine the conclusions. First, despite having four potential combinations (two population pathways and two emissions pathways) only three are presented – the combination of a low emissions pathway (RCP2.6) and a moderate development pathway (SSP2) is not included (see Matrix 1). Secondly, the high emissions scenario of RCP 8.5 arguably lacks credibility as it does not take into account the dramatic reduction in renewable energy technology costs seen since 2004.15Justin Ritchie and Hadi Dowlatabadi, ‘Why do climate change scenarios return to coal?’, Energy, 140:1 (2017), https://bit.ly/3hIi2Zz (checked: 23/01/2023). The case has only been strengthened due to recent progress, particularly in renewable deployment due to cost and energy security concerns regarding fossil fuels following Russia’s renewed aggression against Ukraine. The International Energy Agency’s most recent projection sees renewables overtake coal as the largest source of global electricity generation by early 2025, for example.16‘Renewables 2022’, International Energy Agency, 12/2022, https://bit.ly/3GcPC3t (checked: 23/01/2023).

Matrix 1: Climate-development scenarios used to develop migration assessments in the Groundswell Report

It is also important to note that the Groundswell studies focus on internal migration, which they conclude will comprise the vast majority of climate-linked migration. This was also acknowledged by expert testimony to the Home Affairs Sub-Committee of the House of Lords’ Select Committee on the European Union (EU) in 2020.18Roger Zetter, ‘Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee, Uncorrected oral evidence: Climate change and migration’, House of Lords, 11/03/2020, http://bit.ly/3hsiRFf (checked: 23/01/2023). However, this fact is frequently lost when the report is referenced more widely.

Further cautions can be found in a Rapid Evidence Assessment completed for the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in 2021. The assessment claims that the Groundswell research ‘“reduces the future to climate” plus population growth’ and that it, like ‘all other’ high-end projections makes:

…no allowance for in-place adaptation, despite the extensive evidence of in-place adaptation provided by studies of present-day climate-related migration. For this reason in particular, high-end projections of climate-related migration are not considered credible.19Jan Selby and Gabrielle Daoust, ‘Rapid evidence assessment on the impacts of climate change on migration patterns’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/07/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ep40oj (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 56.

The Government Office of Science also highlights the challenges of predicting migration in the future.20‘…making predictions of migration into the future is beset by problems: formulating a precise quantification is unlikely to be possible as even the data on recent trends are estimated with limited accuracy. Many expert predictions of migration flows have turned out to be significantly flawed.’ See: ‘Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities’, Government Office for Science, 20/10/2011, http://bit.ly/3G8MZjp (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 55. It states: ‘the range and complexity of the interactions between these drivers means that it will rarely be possible to distinguish individuals for whom environmental factors are the sole driver’ for their migration.21Ibid., p. 9. In turn, it is notable that the Groundswell report only focuses on migration induced by slow onset climate change. It does not address natural disasters.

It is finally worth a note of caution that there is no agreement – and to date no appetite for agreement – on how to define a ‘climate migrant’. It is extremely difficult to disentangle ‘climate’ from the other factors which may trigger a person’s decision to move. Even more contentious is the term ‘climate refugee’. As Alex Randall, then-Climate Change and Migration Project Manager at the Climate and Migration Coalition, advised in the aforementioned inquiry held by the House of Lords: ‘If you speak to people from some of the Pacific island states, such as Kiribati and Tuvalu, they actively reject the term “climate refugee”. They do not wish to become that.’22Alex Randall, ‘Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee, Uncorrected oral evidence: Climate change and migration’, House of Lords, 11/03/2020, http://bit.ly/3hsiRFf (checked: 23/01/2023). Dr Caroline Zickgraf, Deputy Director of the Hugo Observatory, has also confirmed that it is not a term used by scholars who study migration.23Alex Randall and Dr Caroline Zickgraf, ‘Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee, Uncorrected oral evidence: Climate change and migration’, House of Lords, 11/03/2020, http://bit.ly/3hsiRFf (checked: 23/01/2023).

In sum, it is important to keep in mind that projections of large numbers of migrants fleeing climate change are worst case and sometimes completely outdated. None are by any means certain and there remains significant scope for shaping the future to prevent the need of people to uproot. However, there certainly are important junctures between climate change and migration which already exist which Britain ought to prepare for. Here, a distinction ought to be made between the ways climate change may exacerbate the movement of people. In most cases, it appears climate change will be one of many factors which cause people to move, mostly internal migration, in keeping with the findings of the Groundswell reports and others. This might be called ‘climate-linked’ migration. In the future, however, there is greater chance for what could be called ‘climate-provoked’ migration, where climate change, in specific cases, is the primary driver. In the next two sections, the two are examined, including their implications for British security.

3.0 Climate-linked migration

Ahead of the most recent UN Climate Change Conference (COP) in Sharm El-Sheikh (commonly referred to as COP27), the UN Environment Programme estimated that the world will experience an increase in temperature of between 2.4°c and 2.6°c by the end of this century,24‘Climate change: No “credible pathway” to 1.5C limit, UNEP warns’, United Nations Environment Programme, 27/10/2022, https://bit.ly/3jqzcLW (checked: 23/01/2023). while the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that an increased frequency of extreme weather events has already exposed millions to acute food and water insecurity in vulnerable regions.25‘Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability’, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, https://bit.ly/3YE46Al (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 9. The world is currently 1.1°c warmer than before the industrial revolution, and while the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has clearly brought down emissions scenarios through the Paris Agreement and subsequent COPs, the target of 1.5°c warming above pre-industrial levels set out in the treaty is still nowhere near to being reached. Indeed, the growing impact of climate change is already more tangible with extreme weather events, including in the UK, and logic follows that it will only get worse. In other words, despite the uncertainty of climate change’s impact on migration and how it will evolve, it will evolve.

The Government Office for Science’s report ‘Foresight: Migration and Global Environmental Change’ makes for a valuable starting point in thinking about the impact climate change might have on migration because it focuses on the importance of an analytical framework and the drivers of change and their interaction, rather than anchoring conclusions in specific numbers of potential migrants.26‘Foresight: Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities’, Government Office for Science, 20/10/2011, http://bit.ly/3G8MZjp (checked: 23/01/2023). Although in trying to model specific numbers the Groundswell Report could be seen as the logical next step following the Foresight Report, the framework is unavoidably lost in the process. Importantly, the Foresight report concludes that preventing harmful environmental (including climate) change will reduce climate-linked migration but not halt it; that migration can be a transformational form of adaptation to environmental change; that environmental change is equally likely to make migration less possible as more probable; and that some cities in low-income countries are experiencing rapid growth but are exposed to environmental change.27Ibid., p. 10.

The findings of both the Foresight and Groundswell reports appear to underpin the Home Affairs Sub-Committee of the House of Lords’ Select Committee on the EU proceedings in 2020, which noted that the majority of climate induced migration is ‘very likely to be domestic’, with minor spillover into neighbouring countries, and will occur ‘primarily in the global south [sic.], internally and between neighbouring countries’.28Dr Ricardo Safra de Campos and Alex Randall, ‘Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee, Uncorrected oral evidence: Climate change and migration’, House of Lords, 11/03/2020, http://bit.ly/3hsiRFf (checked: 23/01/2023). That said, neither report addresses cross border migration in much detail; indeed, just because the majority of climate-linked migration is set to occur within developing countries does not mean that British interests will remain unaffected.

Already, in Syria, a country wracked by years of internal strife, the world has borne witness to how climate change can combine with other factors to provoke migration. The obvious primary ignition of revolution in Syria in 2011 was the Syrian Government’s failure to respond to demands for political change. However, environmental factors and their economic consequences acted as a catalyst for the conflict. Following years of drought, poverty rates in Syria’s urban southern region doubled between 2007 and 2011, compounding pre-existing stress from Palestinian and Iraqi refugees.29Lahcen Achy, ‘Syria: Economic Hardship Feeds Social Unrest’, Los Angeles Times, 31/03/2011, https://bit.ly/3HUQ9bu (checked: 23/01/2023). This exacerbated other stresses caused by poor environmental and resource policies, including unsustainable levels and methods of freshwater extraction.30Shiloh Fetzek and Jeffrey Mazo, ‘Climate, Scarcity and Conflict’, Survival, 56:5 (2014), p. 145. Tensions grew over resources and employment opportunities within cities. The Syrian Government’s policy of offering cash for farmers to return to drought-stricken land inevitably failed.

So while climate change may not be the prime driver of internal or cross-border migration, it will act as an amplifier, even a threat multiplier, in countries and regions with poor governance (especially inadequate preparedness for natural disasters), local conflict, competition over scarce resources, and weak economic growth. Here, it is worth noting that in many developing countries, the agricultural sector often represents a large proportion of the labour force.31Max Roser, ‘Employment in Agriculture’, Our World in Data, 2013, https://bit.ly/3joAc3b (checked: 23/01/2023). Climate and weather related shocks impact on the agricultural sector perhaps more acutely than any other. This can place unbearable pressure upon cities and governments in developing countries which are either under-resourced or not competent enough to adequately deal with its implications. The FCDO’s rapid evidence assessment found that climate and weather related ‘shocks’ are more likely to either lead to rapid internal migration or prevent people from moving at all in the short term, as their resources and capacity to move are reduced. In a warmer world with more frequent, more extreme weather, similar scenarios to that of Syria in 2011 may emerge if cities cannot absorb internal migration.

3.1 Implications for the UK

At this point, the question may arise as to why Britain should care about climate-linked migration, particularly when there are so many other challenges to deal with. The answer is simple: the past eight years have shown that even a relatively small number of people (compared to those internally displaced elsewhere seeking to cross Europe’s borders) can cause significant political and social disruption, evident not just in terms of the horrific death toll in the Mediterranean Sea, and the strain on national resources across Europe, but also through the exacerbation of political tensions at home. Indeed, that the Levant and North Africa are especially vulnerable to climate change and contain a number of pre-existing social and economic tensions, which hostile states, such as Russia, have actively exploited, should be a particular cause for concern. These regions cut across the UK’s main maritime communication line to the Indo-Pacific and border many important British allies and partners.

In this sense, recent events – both climate and non-climate related – show just how vulnerable the UK is to the fallout from climate-linked migration, despite its relative security as an island state at the heart of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). The fallout from the Syrian civil war was felt far and wide, including by Britain. Besides the large number of people who left Syria in 2015, Daesh, which grew from the war, kidnapped and killed British citizens and posed a significant threat to the UK’s interests in the Levant and Mesopotamia.

3.1.1 Impact on domestic politics

British citizens expect a strong border and a fair immigration system, which are both necessary prerequisites for national sovereignty and a core interest according to the Integrated Review.32The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3v8NUtr (checked: 23/01/2023). It should remain HM Government’s policy to ensure those who arrive in the UK do so through legal means. Failure to deal with irregular and illegal migration causes significant political problems in developed countries; an erosion of public confidence in governments to enforce national borders only benefits Britain’s adversaries.

In 2022, just over 44,000 migrants made it across the English Channel to the UK in small boats, but the cost to the British taxpayer has soared into the billions.33Nick Timothy and Karl Williams, ‘Stopping the Crossings: How Britain can take back control of its immigration and asylum system’, Centre for Policy Studies, 05/12/2022, https://bit.ly/3WCScou (checked: 23/01/2023), p.6. If the public perceives the immigration system to be unfair or, worse, to have failed, various political opportunists, who are hostile to all forms of migration, whether legitimate or not, can intervene to stoke public anger. On the European continent, where there have been far larger numbers of migrants – whether due to government policy or illegal migration – more extremist parties have grown in power,34Anthony Edo and Yvonne Giesing, ‘Has Immigration Contributed to the Rise of Rightwing Extremist Parties in Europe?’, EconPol Policy report, 27/07/2020, http://bit.ly/3Deq3x4 (checked: 23/01/2023), p.10. with their propaganda ‘attributing increases in crime to migrant populations or blaming them for burdening societies in the EU and criticising EU migration policies.’35Europol, ‘European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report’, Publications Office of the European Union, 13/07/2022, http://bit.ly/3JbTPGn (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 57. This fraying of confidence can severely undermine domestic institutions.

3.1.2 Impact on Britain’s allies, partners, and reputation

Finally, it is clear that migration flows – even climate-linked – can be effectively weaponised for geoeconomic and geopolitical gain, evident with Russia’s intervention in the Syrian civil war. In 2016, Philip Breedlove, then Commander, then Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, told the United States Senate Armed Services Committee that the consequent Mediterranean migration crisis was being exploited by Russia and the Assad regime to create divisions within NATO and Europe. He argued that weapons with little military utility were being used ‘to get people on the road and make them someone else’s problem…make them a problem for Europe to bend Europe to the will of where they want them to be.’36‘Gen. Breedlove’s hearing with the House Armed Services Committee’, US European Command, 25/02/2016, http://bit.ly/3WDGCJi (checked: 23/01/2023).

An even more explicit form of weaponisation was seen in 2022 when Belarus propelled several hundred Iraqis over its borders with Poland and Lithuania in an attempt to force the EU to lift sanctions on the regime of Alexander Lukashenko, the President of Belarus.37Mark Galeotti, ‘How Migrants Got Weaponised’, Foreign Affairs, 02/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3Vaispi (checked: 23/01/2023). Mateusz Morawiecki, Prime Minister of Poland, turned to NATO and the UK for help; HM Government responded by dispatching over 140 specialists from the Royal Engineers to assist.38‘UK to provide engineering support to Poland amid border pressures’, Ministry of Defence, 09/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3WHiJ4s (checked: 23/01/2023). Although this example is not related to climate change, it raises questions for the future, especially if there are higher volumes of climate-linked migration from the Levant and North Africa.39Andrew Roth, ‘Polish PM urges “concrete steps” by Nato to address border crisis’, The Guardian, 14/11/2021, http://bit.ly/3XXJMZD (checked: 23/01/2023). Scenarios could emerge whereby hostile states, such as Russia, create or exploit other migration corridors, as with the crisis in Syria from 2011.

Moreover, Britain’s NATO allies, particularly to the south of the alliance, have sought to draw the alliance into the linked issues of climate change and migration. NATO’s Climate Change and Security Impact Assessment, conducted in June 2022, ‘calls for a fundamental transformation of NATO’s approach to defence and security and sets NATO as a leading international organisation in understanding and adapting to climate change.’40‘Climate Change and Security Impact Assessment’, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, http://bit.ly/3UNnrfH (checked: 23/01/2023). The first High-Level Dialogue on Climate Change and Security was held in Madrid on the margins of the 2022 NATO Summit in Spain.41‘2022 NATO Public Forum | Day 1 | High-Level Dialogue on Climate and Security [28 JUN 2022]’, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation via Youtube, 28/06/2022, http://bit.ly/3Eq9mQ2 (checked: 23/01/2023). This is predictable: host countries often seek to sway the agenda to suit their own interests. Spain is located much closer to North Africa and therefore more concerned with Mediterranean security threats, including migration, which is projected to increase in volume as climate change intensifies. The risk here is that, through NATO, the UK might be distracted from its core mission – defending against state based threats.

Finally, at a higher diplomatic level, the issue of climate-linked migration itself is also open to exploitation. Dividing lines between climate being a major driver of migration versus a more nuanced view in which climate change is one of many factors are already emerging. The problem, however, is that this nuanced view – unless exceptionally well crafted – rarely captures the political high ground. Consequently, the narrative that climate change is the cause of all ills is increasingly gaining traction, which could harm Britain’s international relations as a historic emitter, both with nations that experience higher levels of emigration due to the perceived threat of climate change, but also others nearby that would consequently experience greater migratory pressures.

A better understanding of the link between climate change and extreme weather events through the development of attribution science would benefit all involved. Currently, it is insufficiently developed to be reliable, leaving space for vexatious litigation or the development of divisive narratives from the UK’s competitors. Greater knowledge of the multifaceted and complex factors driving migration flows abroad would provide a clearer picture and a common understanding between countries based on scientific evidence.

4.0 Climate-provoked migration

Climate-provoked migration is what is defined here as the forced displacement of people directly by slow-onset climate change, especially sea level rises. This is where climate change renders an area of previously habitable land completely uninhabitable. Climate-provoked migration flows may be much smaller than other migratory flows, and therefore pose less of a threat to the UK. However, there is a risk of humanitarian disaster, especially should the world not reach its Paris Agreement carbon mitigation target of no more than 1.5°c of warming above pre-industrial levels, including for many of Britain’s historic friends.

Climate-provoked migration would have the largest impact on Small Island Developing States (SIDS), which are a distinct group of geographically remote countries, primarily in the South Pacific and Caribbean, which face unique social and environmental challenges. The aggregate population of all the SIDS is 65 million, slightly less than 1% of the world’s population.42‘About Small Island Developing States’, Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States, No date, https://bit.ly/3DfczkF (checked: 23/01/2023). Twenty-five of the 56 Commonwealth nations that share a historic bond with the UK are classified as SIDS (see Box 1).

SIDS receive a great deal of attention in international climate politics. This is because these small countries are in the greatest danger from rising sea levels and other consequences of climate change, but have released the smallest amount of greenhouse gas emissions. SIDS tend to have small populations, which means even the maximum level of migration from them would be small compared to migration flows in other parts of the world. That said, the threat they face from climate change is systemic and their ability to deal with it is often practically non-existent, either due to a lack of financial resources to invest in adaptation or geographical setting. While the term ‘climate refugee’ is not used by migration experts due to the complicated nature of migration and the fact there is no agreed definition, it would be future inhabitants of tiny SIDS who lose their entire home country to sea level rise who would surely suit such a label.

4.1 Implications for the UK

4.1.1 Diplomacy and loss and damage

In climate diplomacy, the SIDS group, which is comprised of 38 UN members and 20 non-UN members or associate members of UN regional commissions, has prioritised the receipt of payments from the leading emitters for ‘loss and damage’ – resulting from climate change – for over three decades. COP27 resulted in the establishment of a new ‘loss and damage’ fund. Yet, while the establishment of the fund might be seen as a step in the right direction for SIDS and some non-governmental organisations, the politics and negotiations of actually financing it will likely remain as contentious as its establishment. Loss and damage has been problematic because it places a potentially unlimited liability on developed nations, including the UK, which under the UNFCCC bear more responsibility for climate change as historic emitters. The inability of developed nations to meet their own promise made in 2012 of US$100 billion (£81.2 billion) per year in international climate finance by 2020 was a source of conflict at COP26 in November 2021.

International debates around climate-linked migration and loss and damage finance can be exploited by Britain’s adversaries and competitors. For example, as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has not yet reached the status of a ‘high income economy’, it seeks to sidestep the same responsibility for climate change under the UNFCCC, despite having become the world’s largest emitter and the world’s second largest economy.43For a more detailed examination of the PRC’s discursive statecraft around climate change and the Common But Differentiated Responsibilities principle, see: William Young and Jack Richardson, ‘China’s carbon-intensive rise: Addressing the tensions’, Council on Geostrategy, 30/05/2022, https://bit.ly/3VfB8UK (checked: 23/01/2023). In the loss and damage debate, the PRC has regularly insisted on the creation of the fund,44Simon Jessop and William James, ‘Developing countries, China seek “loss and damage” fund – draft proposal’, Reuters, 02/11/2022, https://bit.ly/3BVBZTz (checked: 23/01/2023). but refused to pay into it now that it has been established. Xie Zhenhua, the PRC’s Special Climate Envoy, reiterated the Chinese position at COP27 that the PRC is still a developing country, and as such had no obligation to provide financial assistance to poorer nations.45Rod Oram, ‘“Developing” China won’t pay into climate loss fund’, Newsroom, 20/11/2022, https://bit.ly/3Gchd4C (checked: 23/01/2023).

The fund seeks to facilitate the flow of ‘new, additional, predictable and adequate financial resources to assist developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in responding to economic and non-economic loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change.’46‘Funding arrangements for responding to loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including a focus on addressing loss and damage’, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 23/11/2022, https://bit.ly/3YEluFb (checked: 23/01/2023). If the fund was successful in increasing the resilience of the most vulnerable countries, it would directly suppress future levels of climate-linked migration.47It is worth noting a good caveat on adaptation and migration from the FCDO’s rapid evidence assessment: ‘There is strong evidence that small-scale adaptations to climate-related shocks and hazards, especially adjustments to agricultural livelihoods and practices and improved infrastructures, can reduce migration pressures. However, there is also strong evidence of adaptation measures, or what may be called “maladaptation”, contributing to displacement and migration, including flood protection initiatives, coastal defence projects, dam building, agricultural development projects and land acquisition.’ See: Jan Selby and Gabrielle Daoust, ‘Rapid evidence assessment on the impacts of climate change on migration patterns’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/07/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ep40oj (checked: 23/01/2023). However, the loss and damage pot will likely remain underfunded due to its contentiousness and the glacial speed of UN processes.

In the meantime, the chance of keeping global warming within 1.5°c of pre-industrial levels appears to be becoming more unrealistic with every passing day. Indeed, away from international organisations and the media, this is quietly admitted by many experts in the area of climate diplomacy. While it is a hope that nations might yet find the political will to meet their commitments, a more likely outcome should be prepared for: some SIDS may be rendered uninhabitable for humans or lost entirely to sea level rises, regardless of the success of fundraising for adaptation.

In the increasingly likely case that the Paris Agreement fails, there will be a rise in displacement from those who live within the most vulnerable SIDS. In this case, to avoid humanitarian disaster, Britain might be called upon to take its ‘fair share’ of displaced people.48It is worth noting here that not all SIDS are threatened to the same extent due to differences in their economies or geography. In total, the population of Commonwealth SIDS in 2021 was around 25.5 million. However, Singapore (4.5 million) or Papua New Guinea (9 million) do not face the same risks as Tonga (106,759) and the British Virgin Islands (30,423), who will find it significantly difficult or potentially impossible to adapt to climate change due to geography and the size of their economies, and their inhabitants may have no choice but to relocate. As mentioned above, there are 25 Commonwealth SIDS: these are the nations the UK should prioritise its efforts in helping with resettlement. This helps to compartmentalise the issue and increase efficiency by avoiding UN processes to a degree, but may also be seen as more legitimate by the British public and publics of other Commonwealth nations due to shared historic bonds. The British public has time and again shown immense capacity to welcome those in genuine need if the need for resettlement is legitimate.

Nevertheless, although some resettlement may eventually be necessary, every effort should be made to help those countries to adapt and become more resilient to climate change. This would minimise the amount of resettlement required, but more importantly prevent entire nations, with their unique histories and cultures, from disappearing entirely from the map.

4.1.2 Building resilience in the Commonwealth

Commonwealth leaders committed to protecting the environment in the Langkawi Declaration.49‘Langkawi Declaration on the Environment, 1989’, The Commonwealth, No date, https://bit.ly/3Geiokg (checked: 23/01/2023). This was one of the world’s first collective statements to name greenhouse gas emissions as one of the leading problems facing the planet. The Climate Change Programme of the Commonwealth Secretariat focuses on strengthening the resilience of Commonwealth countries to the negative impacts of climate change. It provides member countries with measures and support for mitigating and adapting to a changing climate. As of August 2022, the programme had secured US$53.1 million (£43.1 million) for adaptation and mitigation, including US$3 million (£2.4 million) as co-financing.50‘The Commonwealth and Climate Change’, The Commonwealth, No date, https://bit.ly/3WvKYme (checked: 23/01/2023).

The Commonwealth could provide a vehicle for more direct financing and cooperation with some of the world’s most vulnerable states. It would provide the British taxpayer with more influence, transparency, and direct accountability than providing money to UN programmes. It could also provide an opportunity to work more with other more developed economies within the Commonwealth with whom the UK is forging stronger ties with, such as Singapore, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Britain has already worked extensively through its existing development programmes, for example on ‘Building Urban Resilience to Climate Change in Tanzania’, the ‘Infrastructure for Climate Resilient Growth in India’ and the ‘Bangladesh Climate Change and Environment Programme’.51For example, see: ‘Building Urban Resilience to Climate Change in Tanzania’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s Development Tracker, 04/08/2022, http://bit.ly/3UuipoN (checked: 23/01/2023).

The inability of developed nations to meet prior promises around climate finance, the strained debate around the establishment of the fund, and the scramble for fossil fuels witnessed in Europe following Russia’s renewed aggression against Ukraine, have inevitably strained relations with many developing countries, who have (justifiably) cried foul.52‘How Europe’s Rush to Buy Africa’s Natural Gas Draws Cries of Hypocrisy’, Mozambique360, 12/07/2022, https://bit.ly/3hDhnsw (checked: 23/01/2023). The use of worst case scenarios (such as with the Groundswell report) to directly link migration patterns to climate change has the further potential to poison relations between ‘historic emitters’ and those developing economies which are expected to endure the greatest effects of climate change and any associated internal or cross-border migration (as discussed in section 3.0).

Therefore, it would be wise and in keeping with Cleverly’s new doctrine of ‘patient diplomacy’ for the FCDO to update its International Development Strategy to pursue new routes for International Climate Finance (ICF) and more ways to work directly with Commonwealth SIDS to boost resilience and prosperity alike, rather than relying almost exclusively on the drawn out, combative, and exploitable UN processes. The UK can hold its head high on the issue of climate finance, including its announcement of tripling funding for adaptation programmes from £500 million in 2019 to £1.5 billion in 2025 and the rollout of Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) with South Africa, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

None of this is to say that Britain should only engage with Commonwealth nations in its climate diplomacy. There are many strategically important nations which HM Government should engage with which are also vulnerable to climate change. Now that the COP presidency has moved on from the UK, Britain should explore the creation of more platforms to conduct even more effective climate diplomacy to leverage more international climate finance and enhance resilience. The Commonwealth is one option which is woefully underutilised, but there are other new platforms for direct cooperation like JETPs or the Bridgetown Initiative, which has been steered by the Prime Minister of Barbados, which the UK should seek to lead in the development of.53Catherine Osborn, ‘The Barbadian Proposal Turning Heads at COP27’, Foreign Policy, 11/22/2022, https://bit.ly/3IhxFC4 (checked: 23/01/2023).

This would demonstrate additional British climate leadership and is further within the UK’s interest as it could boost foreign resilience faster than the UN’s loss and damage fund, therefore diminishing climate change’s importance as a driver for migration while also improving British ties with its Commonwealth partners.

Box 1: SIDS (Commonwealth members emboldened)54Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Cook Islands, Niue, and Turks and Caicos Islands have been excluded as they are not official Commonwealth members, despite being Associated and Overseas Territories. See: ‘Associated and Overseas Territories’, Commonwealth Network, No date, https://bit.ly/3vc44SK (checked: 23/01/2023).

| American Samoa | Maldives |

| Anguilla | Marshall Islands |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Martinique |

| Aruba | Mauritius |

| Bahamas | Federated States of Micronesia |

| Bahrain | Montserrat |

| Barbados | Nauru |

| Bermuda | New Caledonia |

| Belize | Niue |

| British Virgin Islands | Palau |

| Cabo Verde | Papua New Guinea |

| Cayman Islands | Puerto Rico |

| Commonwealth of Norther Marianas | St. Kitts and Nevis |

| Comoros | St. Lucia |

| Cook Islands | St. Vincent and the Grenadines |

| Cuba | Samoa |

| Curacao | São Tomé and Príncipe |

| Dominica | Seychelles |

| Dominican Republic | Singapore |

| Fiji | Sint Maarten |

| French Polynesia | Solomon Islands |

| Grenada | Suriname |

| Guadeloupe | Timor-Leste |

| Guam | Tonga |

| Guinea-Bissau | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Guyana | Turks and Caicos Islands |

| Haiti | Tuvalu |

| Jamaica | US Virgin Islands |

| Kiribati | Vanuatu |

5.0 Conclusion

Climate-linked and climate-provoked migration will affect British interests in different ways. While the linked variety may have the most direct impact on the UK’s security and reputation, the provoked form may wipe out many smaller nations. Mitigating climate change through carbon emission reductions will diminish the importance of both forms as a driver for migration. HM Government should therefore continue the UK’s climate change mitigation efforts: it should maintain and improve domestic leadership on reducing Britain’s own emissions through innovation and deployment of clean technologies, industries, and services, thus acting as a role model for other countries.

Simultaneously, the high degree of uncertainty in volume and form that climate-linked and climate-provoked migration may take means that HM Government should first seek out no-regrets options. It should seek to improve its own monitoring capacity to better understand migration flows to the UK and internal and cross-border migratory patterns overseas and how climate change interacts with them. Maintaining public confidence in its immigration system at home is crucial, so it should be wary not to open the British immigration system up to abuse when deciding climate change policy.

It should also seek to build resilience overseas. This could be advising and cooperating with larger states so that they are better prepared to deal with natural disasters and shock migration to enhance stability, or working with particularly vulnerable SIDS to help them adapt to climate change and provide the people there with options should the worst happen. HM Government would also do well to work with other members of the Commonwealth, in which 2.63 billion people live, to increase its capacity to help the most vulnerable members deal more effectively with climate change.

Finally, it is clear that there is a risk to HM Government’s international engagement in the oversimplification of discourse related to climate change, including climate-linked migration. HM Government should challenge divisive narratives that can be exploited by Britain’s competitors and adversaries, but engage constructively increasing knowledge and in creating regional frameworks to help with migratory pressures.

5.1 Recommendations

5.1.1 Improve national resilience

- Publish an annual Cabinet Office report on migration flows abroad and to the UK. The increased frequency of Channel crossings has undermined public confidence in Britain’s immigration system and the Home Office’s response has mostly focused on protecting the border. Given the frustration of attempts to implement the UK-Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership, Britain will likely remain a destination for some time. An annual report on legal, illegal and mixed flow migration to the UK would build domestic confidence, and help to improve reporting and transparency of arrivals, detentions and removals of different types of migrants to Britain. The report should also cover migration flows from countries which are deemed to be most at risk from climate change. This would help to identify the primary factors driving internal and cross border migration, including by asking the question: ‘in rank order, what are the factors driving the movement of people?’

- Benchmark the volume of mixed migration flows and acceptance rates against other countries and adjust accordingly. In order not to attract an undue proportion of mixed migration flows, Britain should consider adjusting its own acceptance rates according to its domestic needs and compared to the acceptance rates of other similar countries. The benchmarking, focused on asylum seeking, currently carried out ad hoc by journalists at The Times,55Tom Calver and Hugo Daniel, ‘Why can’t Britain control migration?’, The Times, 15/10/2022, http://bit.ly/3O5WVft (checked: 23/01/2023). should be part of the Cabinet Office’s report. However, strong support should continue to be offered for genuine refugees where there is clear geostrategic and humanitarian logic, such as with the Hong Kong British Nationals (Overseas) visa, and the Ukrainian and Afghani programmes.

- Be wary of exposing the British immigration system up to further abuse. The Modern Slavery Act, though of course well intended, has been abused by economic migrants seeking to enter the UK illegally, often via criminal traffickers who operate in the English Channel.56Nick Timothy and Karl Williams, ‘Stopping the Crossings: How Britain can take back control of its immigration and asylum system’, Centre for Policy Studies, 05/12/2022, https://bit.ly/3WCScou (checked: 23/01/2023). HM Government should be cautious when passing new legislation or creating policy of opening itself up to such claims further when it comes to ‘climate refugees’, which does not yet have a definition. It should prioritise the creation of legitimate and accountable routes for those in genuine need.

5.1.2 Build resilience overseas

- In the most vulnerable states, prepare for the worst. In the ‘refresh’ of the Integrated Review, HM Government should make building climate resilience a priority. The original iteration of the Integrated Review had a point on resilience: ‘to strengthen adaptation to the effects of climate change that cannot be prevented or reversed, supporting the most vulnerable worldwide in particular’.57The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3v8NUtr (checked: 23/01/2023). This should become a core part of HM Government’s diplomatic efforts, with a particular focus on cities in vulnerable states to increase resilience to shock migration (through working with organisations like the Mayor’s Migration Council) and Commonwealth SIDS.58The Mayors Migration Council is a mayor-led coalition that accelerates ambitious global action on migration and displacement.

- Work with other Commonwealth member states directly and improve the Commonwealth Secretariat’s capacity to build climate resilience. The International Development Strategy promised a balance between adaptation and mitigation funding in the UK’s International Climate Finance.59‘The UK government’s strategy for international development’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 14/05/2022, https://bit.ly/3i88K9r (checked: 23/01/2023). However, many Commonwealth SIDS contribute next to nothing in terms of emissions and yet are the most exposed to the consequences of climate change. The UN process for ICF is liable to political manoeuvring from competitors, including in discussions over loss and damage. But the problem at hand – climate-linked migration – cannot be solved unilaterally. The UK should work with other Commonwealth nations to expand the Commonwealth Climate Change Programme’s capacity, and empower local populations and institutions to adapt and manage internal displacement with the greatest degree of independence possible. It should likewise work with Barbados to develop the new Bridgetown Initiative. Working with Commonwealth nations directly would be preferable to investing in higher level programmes with less transparency or accountability for the British taxpayer.

- Create a Commonwealth forum to prepare for the regrettable but possible eventuality that some resettlement from some Commonwealth nations may be necessary. This Commonwealth-wide forum would examine the possibility of creating a Commonwealth resettlement mechanism in partnership with Commonwealth nations with strong institutional capacity and broad economic shoulders, such as Australia, Canada, India, and New Zealand. Discussions would include which Commonwealth SIDS are in the most danger from rising sea levels and extreme weather events, which may potentially need legitimate routes for resettling citizens, and in which Commonwealth country inhabitants of a given Commonwealth SID would be best resettled.60It should be clear from the start that the scheme should only be set up for those in desperate need of resettlement in the event a low-income SIDS becomes completely uninhabitable due to slow onset climate change. It should not aim to replicate New Zealand’s failed ‘experimental humanitarian visa’ in 2017, which was abandoned within six months after the New Zealand government realised that Pacific Islanders did not want it. Likewise, Kiribati, one of the most vulnerable SIDS in the world, had a ‘migration with dignity’ policy to address the need to move their citizens in the event of climate change, however, it abandoned it in favour of an approach focused on economic prosperity, adaptation, and mitigation. The latter is the correct policy which should be the main focus of British diplomatic efforts on climate change. However, beginning discussions on the potential for establishing legal, safe routes to safety, ready for the worst case scenario, is a no-regrets option.

- Maintain and improve response capacity to support affected populations following a disaster. The UK responded well to the 2022 Pakistan floods, with new networks, procedures, and avenues of response established. For the future, if patterns in natural disasters are identified, training with the local military to enhance domestic capabilities, or the forward position of the Royal Navy and other units to assist in disaster recovery – as is seen in the Caribbean via Atlantic Patrol Tasking North – may be beneficial.61‘Atlantic Patrol Tasking North’, Royal Navy, No date, http://bit.ly/3hDW2OU (checked: 23/01/2023).

- Prepare for migration to be weaponised. HM Government supported Poland and Lithuania when Belarus weaponised migration flows against both. There is no reason not to expect other aggressors to exploit migration for geopolitical or geoeconomic effect. Britain should work to improve contingencies, frameworks, and planning for such scenarios through the NATO’s Civil Contingencies programme, newly established European Political Community or bilaterally.

5.1.3 Challenge divisive narratives

- Address the division between developed and developing countries due to oversimplified or poorly crafted narratives. HM Government should make narrative, analytical, and practical contributions which help progress and manage the debate over the next decade. This should include consideration of if and how the UK pursues ‘A deeper and shared understanding…of the multi-layered and interdependent nature of the risks people face and how climate change shapes displacement patterns’,62‘Global Report on Internal Displacement 2021’, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 20/05/2021, http://bit.ly/3NWlSdc (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 90. as recommended by the IDMC. A valuable initial step would be for the Government Office for Science to prepare a report on climate attribution science and the link between climate change and extreme weather events.

- Support the development of regional refugee and migration frameworks within vulnerable countries. HM Government should seek to help vulnerable states manage times of particular migratory pressure. Localised movement of people may be one of the best forms of adaptation, especially for slow onset climate change, and viewing localised migration through the lens of the labour market may be helpful. One example would be the East African Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s free movement protocol.63The Intergovernmental Authority on Development in East Africa has a ‘free movement protocol’ that specifically addresses disasters where people may need to move preemptively, as well as after its occurrence. See: ‘About’, Intergovernmental Authority on Development, No date, http://bit.ly/3A6YxzR (checked: 23/01/2023).

- Be open minded but cautious about attribution of climate change to migration. There is an increasingly accepted scientific approach to the attribution of extreme weather events, particularly with slow onset climate change,64See: ‘Climate change 2021: The physical science basis’, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 25/07/2022, http://bit.ly/3UBosYQ (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 162 and Jan Selby and Gabrielle Daoust, ‘Rapid evidence assessment on the impacts of climate change on migration patterns’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/07/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ep40oj (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 4, p. 11. however, it remains in its nascency.65‘“My personal feeling about attribution science,” said Horton, “is that it’s less a revolution in our understanding, and more a revolution in how we apply knowledge to attribute blame and apportion responsibility, and perhaps most importantly, to inform and motivate communities and stakeholders to take action.”’ Radley Horton, of Columbia Climate School’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, quoted in: Renee Cho, ‘Attribution Science: Linking Climate Change to Extreme Weather’, State of the Planet, 04/10/2021, http://bit.ly/3E0ArYF (checked: 23/01/2023). When a person decides to move, especially over long distances, it is rarely due to a single push or pull factor. There is great potential, as seen in the debate around loss and damage at the UN level, for competitors to cynically use such narratives against the UK and open societies for political gain. It may also expose the British immigration system to abuse.

- Discourage NATO’s involvement in border enforcement. It should not be considered an appropriate use of NATO resources, which should be focused on the deterrence of geostrategic threats, above all else Russia, to uphold the EU’s common border. This border has gained greater salience since the formation of the Schengen travel area. HM Government ought to project narratives which explain why it is unethical for EU member states, especially those with a poor history of meeting their NATO defence spending targets, to expect to rely on the resources of Britain and other non-EU NATO alliance members to foot the bill for policing their borders. The UK should instead encourage them to boost their national border enforcement capacity, recognising that the European Border and Coast Guard Agency – ‘Frontex’ – will not always meet the operational or political needs of the situation.

About the authors

Jack Richardson is the Climate Programmes Coordinator at the Conservative Environment Network, an independent forum that brings together Conservatives who support decarbonisation and conservation. He is also James Blyth Early Career Associate Fellow in Environmental Security at the Council on Geostrategy. He studied Politics at the University of Exeter and is embarking upon a Masters degree in International Political Economy at King’s College, London.

William Young is a Director at BloombergNEF, Bloomberg’s strategic research business and climate lead on the East-West focused New Economy Forum. He was formerly Chief of Staff to the Chief Executive Officer and Chief Operations Officer and prior to that was instrumental in launching BloombergNEF’s research capabilities and advising clients on technology, finance, economics, politics and business opportunities in the transition to a low carbon economy. He is also a William Stanley Jevons Associate Fellow in Environmental Security at the Council on Geostrategy. He holds an MSc in International Strategy and Diplomacy from the London School of Economics and an MA (Hons) in Modern History from the University of Oxford.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sam Hall, Director of the Conservative Environment Network; James Rogers, Co-Founder and Director of Research and Patrick Triglavcanin, Research Assistant, at the Council on Geostrategy. They would also like to thank Anatol Lieven, Professor, Georgetown University, Qatar for his input and Samuel Huckstep, Research Assistant, Centre for Global Development, Brigitte Hugh, Research Fellow, Council on Strategic Risks, Alexander Luke, Senior Researcher, Onward, and Dillon Smith, Researcher, Centre for Policy Studies for their contributions to a roundtable discussion on the topic. The Council on Geostrategy is grateful to the Conservative Environment Network (CEN) whose funding has made this study possible.

Disclaimer

This publication should not be considered in any way to constitute advice. It is for knowledge and educational purposes only. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Council on Geostrategy or the views of its Advisory Council.

No. ESPPP02 | ISBN: 978-1-914441-33-2

- 1‘Over one billion people at threat of being displaced by 2050 due to environmental change, conflict and civil unrest’, Institute for Economics and Peace, 09/09/2020, http://bit.ly/3TnAELj (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 2‘Happy New Year Live! London Fireworks 2023 BBC’, BBC via Youtube, 01/01/2023, http://bit.ly/3CiIK25 (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 3Jan Selby and Gabrielle Daoust, ‘Rapid evidence assessment on the impacts of climate change on migration patterns’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/07/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ep40oj (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 40.

- 4In this Policy Paper, the phenomenon will be described as ‘climate-linked migration’.

- 5‘Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities’, Government Office for Science, 20/10/2011, http://bit.ly/3G8MZjp (checked: 23/01/2023). There is no clear definition of a ‘climate migrant’, though the UN’s first Special Rapporteur on Human rights and Climate Change, appointed in March 2022, plans to examine this, see: Michelle Langrand, ‘UN climate expert: I want to find the wormhole between human rights and climate change’, Geneva Solutions, 24/06/2022, http://bit.ly/3Tu2Pba (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 6The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3v8NUtr (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 7‘British foreign policy and diplomacy: Foreign Secretary’s speech’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 12/12/2022, https://bit.ly/3PIEcrh (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 8Gaia Vince, ‘The century of climate migration: why we need to plan for the great upheaval’, The Guardian, 18/09/2022, http://bit.ly/3Gptx2b (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 9‘Outlook on Migration, Environment and Climate Change’, International Organisation for Migration, 19/11/2014, https://bit.ly/3WEcxdl (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 10‘Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration’, World Bank, 19/03/2018, http://bit.ly/3E7l6FY (checked: 23/01/2023) and ‘Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration’, World Bank, 13/09/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ek7M15 (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 11Ibid.

- 12See: ‘Global Report on Internal Displacement 2021’, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 20/05/2021, http://bit.ly/3NWlSdc (checked: 23/01/2023) and ‘Global Trends Report 2021’, United Nations High Commission for Refugees, 01/07/2022, http://bit.ly/3Ey7QeZ (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 13‘World Migration Report 2022’, International Organisation for Migration, 01/12/2021, http://bit.ly/3G97lJs (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 14‘Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration’, World Bank, 13/09/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ek7M15 (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 320.

- 15Justin Ritchie and Hadi Dowlatabadi, ‘Why do climate change scenarios return to coal?’, Energy, 140:1 (2017), https://bit.ly/3hIi2Zz (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 16‘Renewables 2022’, International Energy Agency, 12/2022, https://bit.ly/3GcPC3t (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 17‘Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration’, World Bank, 13/09/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ek7M15 (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 320.

- 18Roger Zetter, ‘Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee, Uncorrected oral evidence: Climate change and migration’, House of Lords, 11/03/2020, http://bit.ly/3hsiRFf (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 19Jan Selby and Gabrielle Daoust, ‘Rapid evidence assessment on the impacts of climate change on migration patterns’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/07/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ep40oj (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 56.

- 20‘…making predictions of migration into the future is beset by problems: formulating a precise quantification is unlikely to be possible as even the data on recent trends are estimated with limited accuracy. Many expert predictions of migration flows have turned out to be significantly flawed.’ See: ‘Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities’, Government Office for Science, 20/10/2011, http://bit.ly/3G8MZjp (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 55.

- 21Ibid., p. 9.

- 22Alex Randall, ‘Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee, Uncorrected oral evidence: Climate change and migration’, House of Lords, 11/03/2020, http://bit.ly/3hsiRFf (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 23Alex Randall and Dr Caroline Zickgraf, ‘Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee, Uncorrected oral evidence: Climate change and migration’, House of Lords, 11/03/2020, http://bit.ly/3hsiRFf (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 24‘Climate change: No “credible pathway” to 1.5C limit, UNEP warns’, United Nations Environment Programme, 27/10/2022, https://bit.ly/3jqzcLW (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 25‘Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability’, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, https://bit.ly/3YE46Al (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 9.

- 26‘Foresight: Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities’, Government Office for Science, 20/10/2011, http://bit.ly/3G8MZjp (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 27Ibid., p. 10.

- 28Dr Ricardo Safra de Campos and Alex Randall, ‘Select Committee on the European Union, Home Affairs Sub-Committee, Uncorrected oral evidence: Climate change and migration’, House of Lords, 11/03/2020, http://bit.ly/3hsiRFf (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 29Lahcen Achy, ‘Syria: Economic Hardship Feeds Social Unrest’, Los Angeles Times, 31/03/2011, https://bit.ly/3HUQ9bu (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 30Shiloh Fetzek and Jeffrey Mazo, ‘Climate, Scarcity and Conflict’, Survival, 56:5 (2014), p. 145.

- 31Max Roser, ‘Employment in Agriculture’, Our World in Data, 2013, https://bit.ly/3joAc3b (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 32The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3v8NUtr (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 33Nick Timothy and Karl Williams, ‘Stopping the Crossings: How Britain can take back control of its immigration and asylum system’, Centre for Policy Studies, 05/12/2022, https://bit.ly/3WCScou (checked: 23/01/2023), p.6.

- 34Anthony Edo and Yvonne Giesing, ‘Has Immigration Contributed to the Rise of Rightwing Extremist Parties in Europe?’, EconPol Policy report, 27/07/2020, http://bit.ly/3Deq3x4 (checked: 23/01/2023), p.10.

- 35Europol, ‘European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report’, Publications Office of the European Union, 13/07/2022, http://bit.ly/3JbTPGn (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 57.

- 36‘Gen. Breedlove’s hearing with the House Armed Services Committee’, US European Command, 25/02/2016, http://bit.ly/3WDGCJi (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 37Mark Galeotti, ‘How Migrants Got Weaponised’, Foreign Affairs, 02/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3Vaispi (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 38‘UK to provide engineering support to Poland amid border pressures’, Ministry of Defence, 09/12/2021, https://bit.ly/3WHiJ4s (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 39Andrew Roth, ‘Polish PM urges “concrete steps” by Nato to address border crisis’, The Guardian, 14/11/2021, http://bit.ly/3XXJMZD (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 40‘Climate Change and Security Impact Assessment’, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, http://bit.ly/3UNnrfH (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 41‘2022 NATO Public Forum | Day 1 | High-Level Dialogue on Climate and Security [28 JUN 2022]’, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation via Youtube, 28/06/2022, http://bit.ly/3Eq9mQ2 (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 42‘About Small Island Developing States’, Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States, No date, https://bit.ly/3DfczkF (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 43For a more detailed examination of the PRC’s discursive statecraft around climate change and the Common But Differentiated Responsibilities principle, see: William Young and Jack Richardson, ‘China’s carbon-intensive rise: Addressing the tensions’, Council on Geostrategy, 30/05/2022, https://bit.ly/3VfB8UK (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 44Simon Jessop and William James, ‘Developing countries, China seek “loss and damage” fund – draft proposal’, Reuters, 02/11/2022, https://bit.ly/3BVBZTz (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 45Rod Oram, ‘“Developing” China won’t pay into climate loss fund’, Newsroom, 20/11/2022, https://bit.ly/3Gchd4C (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 46‘Funding arrangements for responding to loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including a focus on addressing loss and damage’, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 23/11/2022, https://bit.ly/3YEluFb (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 47It is worth noting a good caveat on adaptation and migration from the FCDO’s rapid evidence assessment: ‘There is strong evidence that small-scale adaptations to climate-related shocks and hazards, especially adjustments to agricultural livelihoods and practices and improved infrastructures, can reduce migration pressures. However, there is also strong evidence of adaptation measures, or what may be called “maladaptation”, contributing to displacement and migration, including flood protection initiatives, coastal defence projects, dam building, agricultural development projects and land acquisition.’ See: Jan Selby and Gabrielle Daoust, ‘Rapid evidence assessment on the impacts of climate change on migration patterns’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 08/07/2021, http://bit.ly/3Ep40oj (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 48It is worth noting here that not all SIDS are threatened to the same extent due to differences in their economies or geography. In total, the population of Commonwealth SIDS in 2021 was around 25.5 million. However, Singapore (4.5 million) or Papua New Guinea (9 million) do not face the same risks as Tonga (106,759) and the British Virgin Islands (30,423), who will find it significantly difficult or potentially impossible to adapt to climate change due to geography and the size of their economies, and their inhabitants may have no choice but to relocate.

- 49‘Langkawi Declaration on the Environment, 1989’, The Commonwealth, No date, https://bit.ly/3Geiokg (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 50‘The Commonwealth and Climate Change’, The Commonwealth, No date, https://bit.ly/3WvKYme (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 51For example, see: ‘Building Urban Resilience to Climate Change in Tanzania’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s Development Tracker, 04/08/2022, http://bit.ly/3UuipoN (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 52‘How Europe’s Rush to Buy Africa’s Natural Gas Draws Cries of Hypocrisy’, Mozambique360, 12/07/2022, https://bit.ly/3hDhnsw (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 53Catherine Osborn, ‘The Barbadian Proposal Turning Heads at COP27’, Foreign Policy, 11/22/2022, https://bit.ly/3IhxFC4 (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 54Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Cook Islands, Niue, and Turks and Caicos Islands have been excluded as they are not official Commonwealth members, despite being Associated and Overseas Territories. See: ‘Associated and Overseas Territories’, Commonwealth Network, No date, https://bit.ly/3vc44SK (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 55Tom Calver and Hugo Daniel, ‘Why can’t Britain control migration?’, The Times, 15/10/2022, http://bit.ly/3O5WVft (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 56Nick Timothy and Karl Williams, ‘Stopping the Crossings: How Britain can take back control of its immigration and asylum system’, Centre for Policy Studies, 05/12/2022, https://bit.ly/3WCScou (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 57The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, 14/03/2021, https://bit.ly/3v8NUtr (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 58The Mayors Migration Council is a mayor-led coalition that accelerates ambitious global action on migration and displacement.

- 59‘The UK government’s strategy for international development’, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 14/05/2022, https://bit.ly/3i88K9r (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 60It should be clear from the start that the scheme should only be set up for those in desperate need of resettlement in the event a low-income SIDS becomes completely uninhabitable due to slow onset climate change. It should not aim to replicate New Zealand’s failed ‘experimental humanitarian visa’ in 2017, which was abandoned within six months after the New Zealand government realised that Pacific Islanders did not want it. Likewise, Kiribati, one of the most vulnerable SIDS in the world, had a ‘migration with dignity’ policy to address the need to move their citizens in the event of climate change, however, it abandoned it in favour of an approach focused on economic prosperity, adaptation, and mitigation. The latter is the correct policy which should be the main focus of British diplomatic efforts on climate change. However, beginning discussions on the potential for establishing legal, safe routes to safety, ready for the worst case scenario, is a no-regrets option.

- 61‘Atlantic Patrol Tasking North’, Royal Navy, No date, http://bit.ly/3hDW2OU (checked: 23/01/2023).

- 62‘Global Report on Internal Displacement 2021’, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 20/05/2021, http://bit.ly/3NWlSdc (checked: 23/01/2023), p. 90.

- 63The Intergovernmental Authority on Development in East Africa has a ‘free movement protocol’ that specifically addresses disasters where people may need to move preemptively, as well as after its occurrence. See: ‘About’, Intergovernmental Authority on Development, No date, http://bit.ly/3A6YxzR (checked: 23/01/2023).